- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Of bikies and the soul

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

All those years ago when the Literature Board was set up and given a moderate budget, taking over the excellent work of the Commonwealth Literature Fund, many sceptics expressed doubt that our small nation had enough spread of writing talent to warrant what they considered excessive expenditure on books and writers. The record stands for itself and, even if we consider only the established writers who have so far showered us with their works in the 1970s and 1980s, the scheme must be reckoned highly successful. The wonder is, however, that each year new writers spring up with works of high quality as though talent has bred talent or we have established a cultural climate which has allowed the muse ample room to breathe and take flight. Who had heard of Kate Grenville five years ago, Rod Jones or John Sligo three years ago, or Mark Henshaw before April of this year?

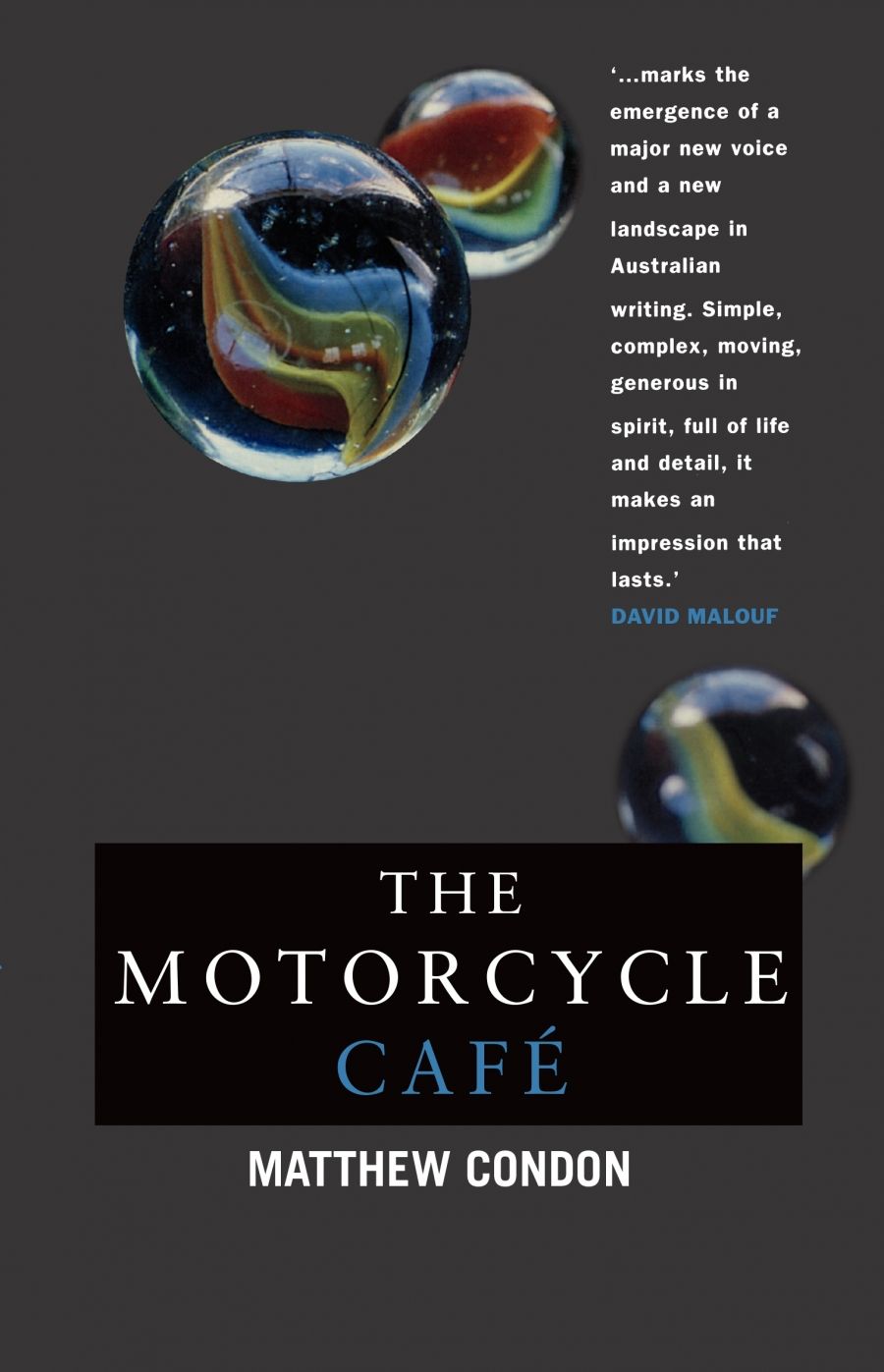

- Book 1 Title: The Motorcycle Café

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $10.95 pb, 170 pp

And now I am delighted to be able to introduce yet another voice (said he, opting for the pompous) – a voice of considerable poetic talent, quiet, firmly intelligent and neatly humorous.

Condon’s story is simple, though, like most simple subjects, harbouring complexities which can only be revealed by structuring the talking through different voices and shuffles in time. George Baker came to this country as a young man bringing with him a wife, the guilty memory of his mother’s death by suicide and the love of a young woman who had been his fiancée, but whom, after his mother’s death, he had forced himself to abandon, though not to reject.

George is a simple handyman with a passion for motorcycles and talk. He is sociable and amiable but every so often astonishes his friend Dave with his ability to see the poetic in the everyday and capture the world in a singular phrase. As Dave says: ‘I think George’s contrasts confused a lot of people. I called them his gears.’

Most nights in the pub George would be surrounded by his mates and would talk and joke, and drink endless beers. At other times he would sit alone with Dave.

He would just sit and spill tobacco on the wooden table, pushing it around with his forefinger and telling me it reminded him of the fields beyond the village. It was the only reason he carried a packet of tobacco, he said, because it was like having his own private field in his pocket. George, he had many gears.

And secrets, which his grandson, born only eight months before George died, tries to uncover and piece together.

The grandson discovers a bundle of letters and photographs hidden in a roof panel under the house where George had built his workshop and darkroom, and where he had spent most of his time. Later he is given his grandfather’s private notebooks and stares at the poetry and sketches they contain, intrigued by the strange soul of this man to whom he is bound but whom he has never seen.

What Condon has given us is, then, a novel of memory and puzzle as we, like his narrator, attempt to recreate the man and the person from stray bits of evidence which, in their solidity, make the ghost incarnate. As the story unfolds we move across four generations and come to understand something of what might be called bonds and love. We also learn of human dignity bulwarked by privacy and the importance of small things, the quotidian, in all our lives.

Condon thinks and writes practically, in images and quickly limned vignettes, tracing and weaving patterns through his elegant prose.

He held the boy’s small hand and smoked in the darkening room, the talk of the women as soft as flapping sheets.

I wondered if my grandfather was too secretive. He kept quiet about things and carried them, like parcels under his arms, into death.

Condon also has that fine knack of crafting a story, winning our respect for him as storyteller. The novel’s structure, with its smooth shifts in time and between narrators, is deftly unobtrusive (with the exception of the third last chapter which should have been reworked and could even have been excised).

Condon has a keen eye for those precise details which give life to the individuality of his characters and particularize a scene or situation.

The cat stares out into the valley, beyond the dead tree near the house, its branches stiff like the upturned feet of a bird. I sit in a chair next to the cat and tie my laces.

It is a poet’s eye, seizing on metaphors and similes, envisioning the correspondences. Condon is at ease with his prose and with the potential of his story for pain, love, and fidelity, those deceptively simple emotions. He is also alert to the tragi-comic possibilities of life and his chapter ‘Thieves’, which describes the descent of relatives and ‘mates’ upon the dead grandfather’s house to souvenir ‘memories’ of George, is a splendid piece of wryly humorous writing.

This is an exceptionally fine first novel, and the usual adjectives ‘confident’ and ‘assured’ are wasted on it. Condon is a writer and a very good one. I await his next work with some eagerness – this one is a joy.

Comments powered by CComment