- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Non-fiction

- Custom Article Title: Brenda Niall reviews 'In the Half-Light' edited by Jacqueline Kent

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Ordinary lives made extraordinary

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Telling one’s own story comes naturally: we are all in some sense autobiographers. There is nothing new in the urge to seek a pattern in a life while living it, to advertise an ego, to explain, confess, justify, understand – or simply to say ‘I was there’. What is new is the comparative ease with which the urge can be accommodated and the ‘self-life’ made into text.

The current interest in the narratives of ‘ordinary people’ is attested by the extraordinary success of Albert Facey’s A Fortunate Life. It may also be seen in some recent and important scholarly enterprises such as the nineteenth century Australian women’s diaries published by Lucy Frost in No Place for a Nervous Lady or the oral histories from which Janet McCalman constructed inner urban Richmond in the depression years as Struggletown.

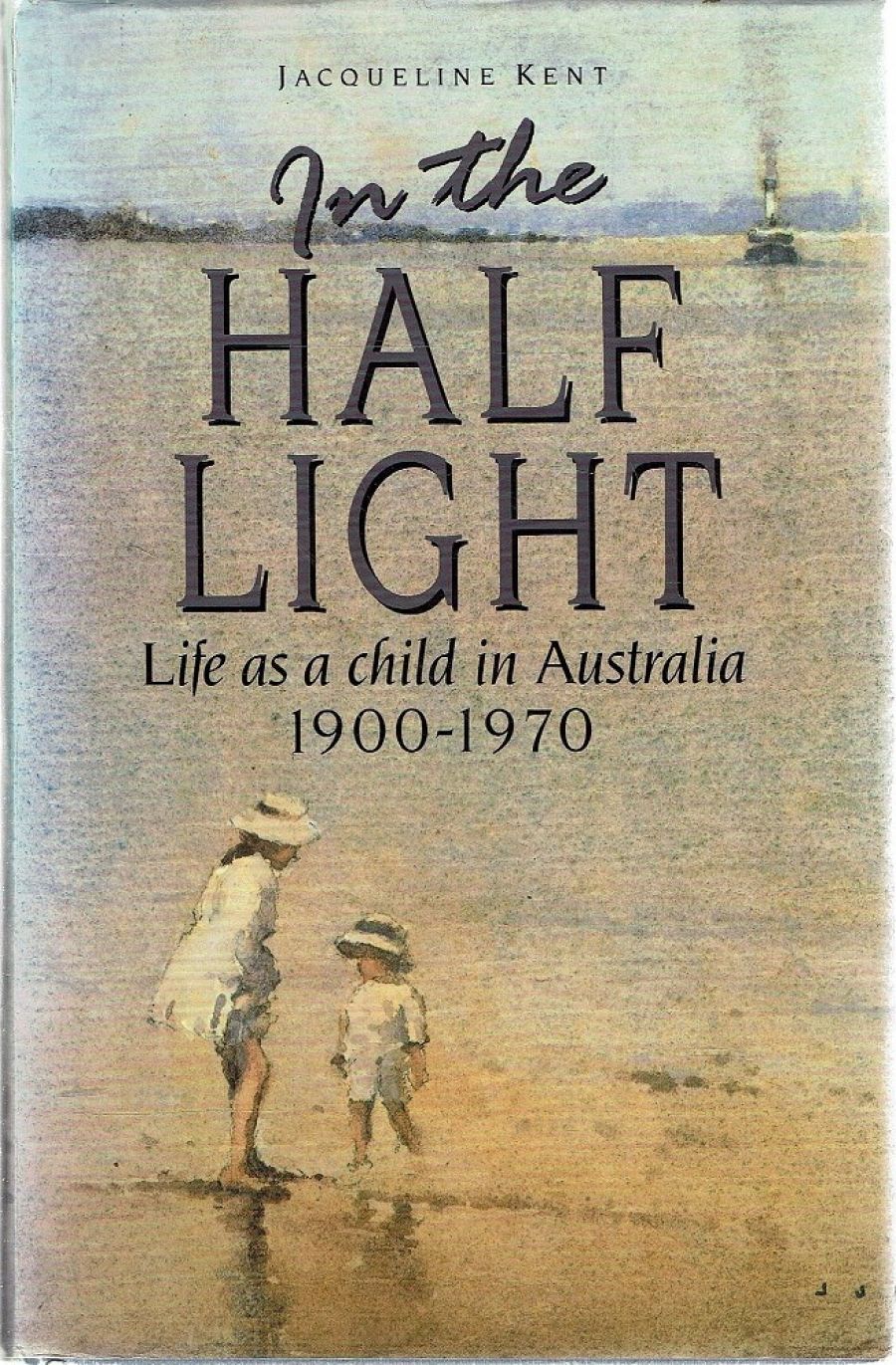

- Book 1 Title: In the Half-Light

- Book 1 Subtitle: Life as a child in Australia 1900-1970

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus and Robertson, $24.95 hb, 265 pp

Most autobiographies, whether formal or informal, see childhood as crucial. Early memories are privileged; and many accounts of a life begin ‘The first thing I can remember …’ Childhood is the undisputed possession of the writing self; it is another country on which only one traveller is qualified to report. Often a vividly realized sense of the self as a child lapses into a conventionalized chronology of events and people: the first chapters of autobiographies are often the best.

In Jacqueline Kent’s In the Half-Light: Life as a Child in Australia 1900–1970 twenty-five anonymous Australians recall their early years. These tape-recorded interviews were chosen from a much larger number. The voices are those of men and women ranging in age from the mid-thirties to their eighties: asked to talk about their childhood they describe backgrounds as diverse as a house in Toorak with three maids, and a wood-and-corrugated-iron ‘humpy’ in western Queensland. There are representatives of lower-middle-class suburbia, country towns, the outback. The disciplined striving of Greek migrants contrasts with the fragmentation of an Aboriginal family. Although there is no controlling idea in this book except that of Australian childhood, certain themes recur: perceptions of race and class, attitudes to England, the Depression, the two World Wars and Vietnam, nationalism, and Australian culture. The emphasis is on the child’s social context: only indirectly does the sense of self come through.

That ‘Australians didn’t speak or write properly, not like people at Home’ was accepted unquestioningly by the daughter of an English-born bank manager in a country town: even today, in her eighties, she ‘can hardly bear to hear newsreaders on the ABC. They sound so Australian’. To a boy from a later generation, the ‘ABC voice’ in which Mr Menzies announced the outbreak of war in 1939 was too English. At least, so he says now, with ironic amusement as he remembers his elders’ dismay when ‘that common Mr Curtain’ took over from Menzies as Prime Minister. This is one example of a pervasive problem: to what extent do these interviews reveal the attitudes of the period they describe? The interaction between speaker and interviewer is obviously important, but we have no way of knowing how the questions were put. The texts have been carefully edited: there are no incomplete or rambling sentences, none of the hesitations and self-corrections that usually impede the flow of talk. It is all smooth, easy, and controlled – but who is in control?

The interviewer chose her twenty-five Australians out of some hundreds whom she interviewed within the last two years. In many ways she chose well: they are an interesting, articulate, and varied group. Whether the ideas they expressed in the 1980s are representative of the times they describe is another matter. One of them recalls his close friendship with an Aboriginal boy in their country town. A girl of the 1930s says that she longed to ‘hug and comfort’ a young Aboriginal parlourmaid when her employer’s son spoke to her rudely. The persecution of Germans in Australia is acknowledged in the discussions of the two World Wars, but firmly placed as wrong. One need not doubt the truthfulness of any individual memory to wonder why, in reading these memoirs, one so seldom finds an illiberal view.

There are other gaps and silences. There is self-censorship in the disparity between what seems most strongly felt in childhood experience and its narrator’s final verdict. One woman who sums up her early self as ‘loved, protected, secure’ has represented her father as an imposing but distant figure, and her mother as chilly and resentful of her children’s claims: ‘“Darling, don’t spoil my dress” was all she said, but I had seen the look on her face and I knew not to attempt to hug her again’.

Some splendid photographs embellish the text. It is disappointing, though, to find in the acknowledgements that many of them come from newspaper files and public archives; they have been matched, more or less appropriately, with the narratives. Some are obvious mismatches: a Toorak childhood is illustrated by a photograph clearly labelled ‘Athelstane, Arncliffe’. The neat, bored child in shorts, white socks, and sneakers, waiting in what looks like a school cloakroom, is wrong in period and physical appearance as well as mood for a 1950s tragedy in a Sydney hospital. Are any of the photographs ‘genuine’? It seems to matter. Why?

Perhaps it comes back to the question of why we read autobiographies as well as write them. There is no single reason, but at least it can be said that without the sense of a particular personality, the sound of a distinctive voice, the text loses much of its value. Our mass culture supplies endless and deadening stereotypes: the single voices of autobiography assert individuality. Thus, the pleasure of reading Jacqueline Kent’s book, with all its fascinating social detail, is qualified a little by her choosing to make the book visually attractive rather than wholly authentic, and by the very smoothness of her editorial control.

Comments powered by CComment