- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This is, above all else, a timely novel. In an afterword describing the Beijing massacre, Nicholas Jose explains that he wrote Avenue of Eternal Peace in 1987. The novel ends with the growing push for democracy, with crowds milling in Tiananmen Square, and with a sense that change might be possible, if precarious. The afterword details the end of such hopes. Jose’s novel therefore has a strange air of elatedness surrounding it. On the one hand it offers a very rare example of contemporary Australian fiction confronting China. The fact that the map of history it stems from has changed so dramatically adds an extra fillip to the reader’s vicarious experience of the ‘new’ China, and especially of Australia’s increasingly blasé encounter with China – up until the recent repression. Perhaps it now stands as a testament to what might have been.

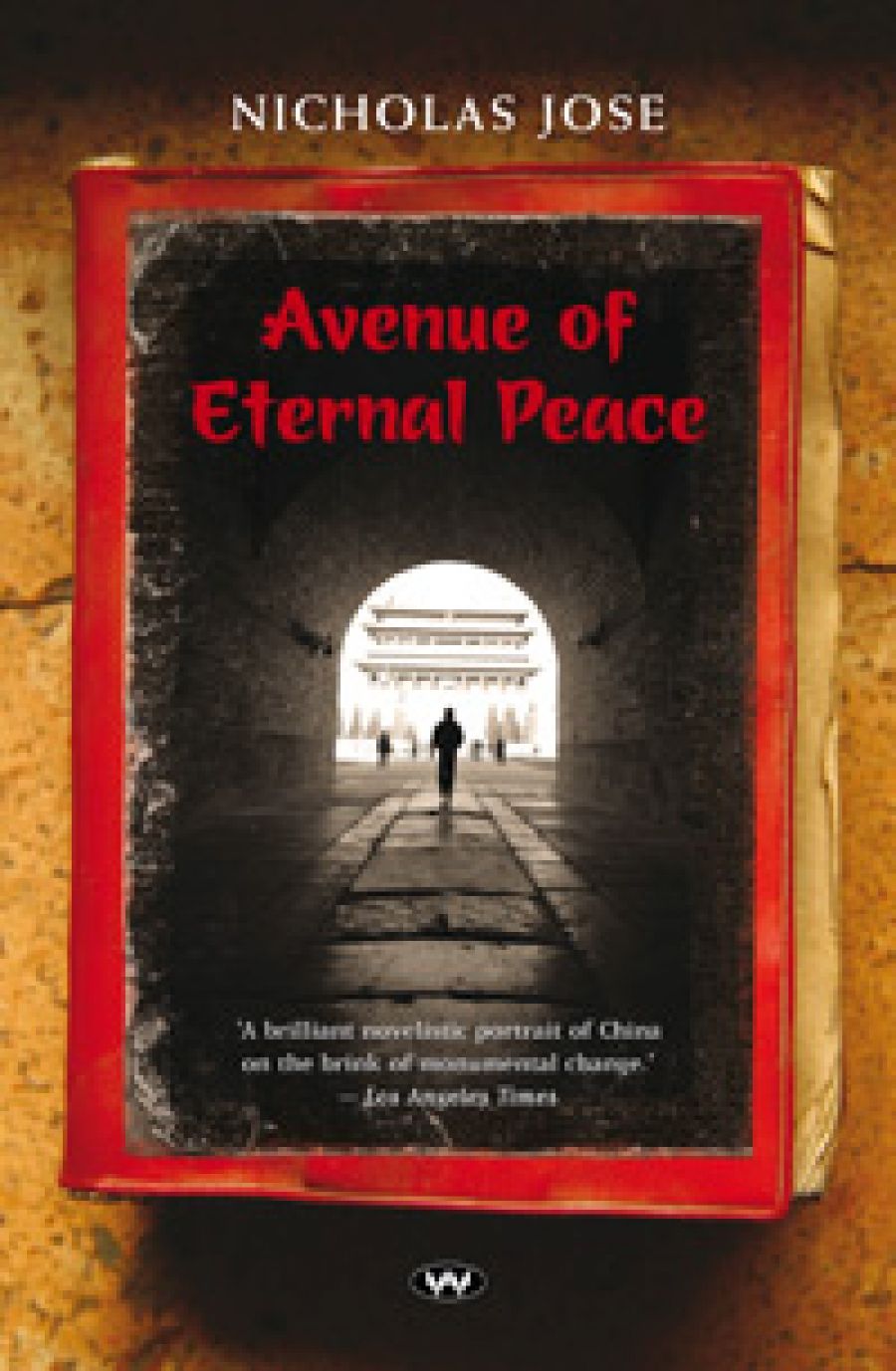

- Book 1 Title: Avenue of Eternal Peace

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 300 pp, $19.99 pb

Jose’s recent fiction has been notable for a superbly controlled, almost epigrammatic prose style. Avenue of Eternal Peace contains moments of such writing, but as it ambitiously expands to offer an overview of contemporary China, at times a kind of literary shorthand appears:

The somewhat arbitrary determination to rediscover Hsu had brought about the kind of connection that might happen or might not, and that makes the world take one shape and not another, and Wally was aware of a single man’s direct participation in the unboundedly complex fate of the planet, as he followed Department Head Cao through the curiously inactive institution.

I find some conceptual as well as stylistic problems in the novel’s dealings with the ‘complex fate of the planet’.

The central narrative in the novel concerns a visit to China by Wally Frith, an Australian medical researcher. As a cancer expert, Frith is in China to pursue the link between Chinese and Western medicine, and specifically to search out an older Chinese researcher, Hsu Chien Lung. In Peking, Frith encounters a variety of Chinese and Western characters as his search for the mysterious Hsu Chien Lung meets official resistance. Frith’s own personal link with China arises out of his grandparents, who were missionaries in Shaoxing. Gradually a very traditional plot unfolds, as Frith finds his search for his ancestral links with China intertwines with his search for Hsu Chien Lung, and also with his pursuit of Jin Juan, who turns out to be the old scientist’s granddaughter.

The maze of coincidences and linkages sits uncomfortably with Juan’s vivid depiction of China. Avenue of Eternal Peace at times reads like a Dickens novel: the same entangling plot, the same concern to show a whole society at work, and perhaps the same danger of slipping into narrative shorthand. It is possible that Jose intends the plot that centres on Wally Frith to be a deliberately old-fashioned piece of stylisation, as a way of evoking something like the Peking Opera that plays a part in the narrative. I’m afraid I never cared enough about Frith to become involved in the reversals and recognitions of his quest.

For me, the true involvement lies in Jose’s fascinating portrayal of the variety and difference of China. Wally Frith is perhaps overworked as the slightly naive Western observer of the mysterious East. But the narrative constantly undermines Wally’s generalisations, and he recognises the dangers present in the temptation to offer summaries of races or nations:

‘Why do we always end up talking of them as “the Chinese”, “they”, “them”, as if they’re a different species. As individuals they’re as different as chalk and cheese. But it’s the larger organism that fascinates us, the group thing, the nation, the race.’

In the course of the novel, Jose offers a series of portraits of individuals to counter that tendency to generalise. Jin Juan, the old scientist’s granddaughter; Eagle, the naive athlete who lives with his mother; Jumbo, the rebellious artist taken up by expatriate American Dulcie; Zhang, the new-style Chinese bureaucrat; the enigmatic and sage Hsu Chien Lung himself – all these figures offer a sense of knowing the individuality of the Chinese. Yet at the same time many of these characters appear to be stick figures whose attributes are slightly two-dimensional. I cannot pronounce on the ‘authenticity’ of these portraits; nevertheless they often appear to be very shadowy figures who exemplify their roles.

These quibbles are mostly set aside in the face of some excellent writing which conveys the sense of an immersion in what is both different and familiar. Jose’s power to startle the reader into a new perception is evident in the image of the pro-democracy crowd suddenly Iinked to the cancer that Wally specialises in, and that killed his wife:

Then it happened. Some friends linked arms, others pushed against them, girls held tight to boys, waists, belts, arms were grabbed, and they became, like cells metastasising, a concentration of’ force.

Like all experiences of what is foreign, Avenue of Eternal Peace offers glimpses of a difference in perspective that can only be fleeting.

Comments powered by CComment