- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In September 1960, Jill Ker, aged twenty-six, left Australia for good. She was off to study history at Harvard and, as it turned out, to make a career as a high-flying academic administrator in the States. The ties she was breaking were those that bound her to her widowed mother and, above all, to Coorain, the thirty-thousand-acre property her father had acquired in 1929 as a soldier settler and where she had spent the first eleven years of her life. The Road from Coorain is her account – all the more moving for being carefully neutral in tone – of how those ties were formed as she grew up and how she reached her decision to break them.

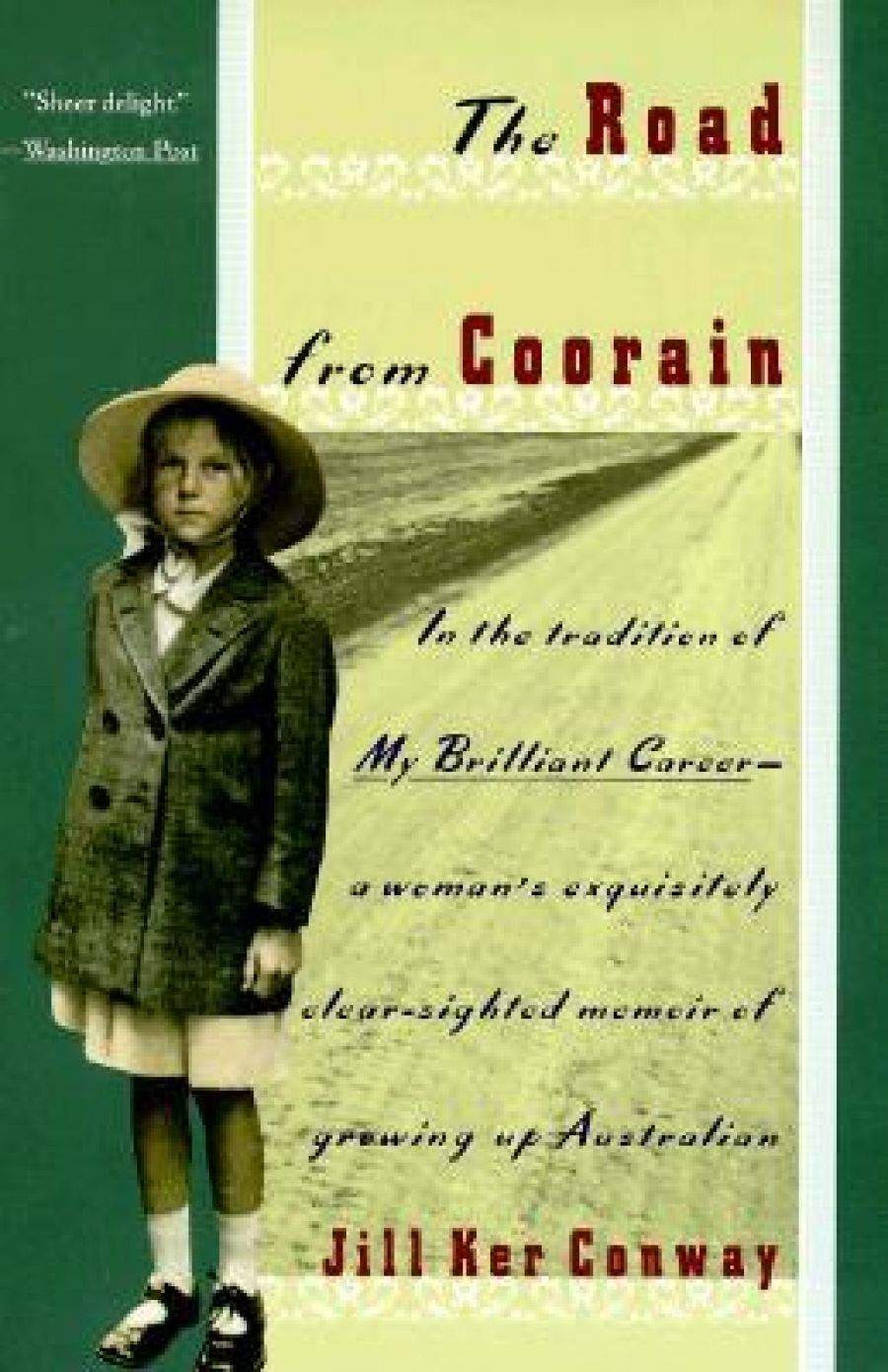

- Book 1 Title: The Road from Coorain

- Book 1 Biblio: William Heinemann Australia, $29.95 hb, 238 pp, 0-85561-321-1

Jill Ker’s mother, a Queenslander, had left school at fourteen to help support a large fatherless family. At sixteen, she headed for Sydney to take up nursing. When she met Bill Ker a decade on, she was the vivacious, capable matron of the small hospital at Lake Cargelligo in western New South Wales. They married a month after meeting and within three years had two sons. According to their daughter, the pair possessed the pioneer virtues in full measure: ‘both were driven to excel, to run the best sheep station, breed the best sheep, raise the brightest children, run the most efficient house’. On the eve of the Depression, they confidently risked everything to take up a soldier settler’s block on the dusty far-west plains of New South Wales, where ‘in the recurring cycles of drought the sand and dust flow like water’.

They called their property Coorain (Aboriginal for windy place) and built themselves a comfortable homestead, the corrugated iron roof of which was at first their only means of collecting water for their tanks. They had no garden, no telephone, no electricity, no neighbours.

By the time Jill was born, her parents’ thrift, hard work, and ingenuity had paid off. She remembers a handsome young couple relaxing on the verandah after the day’s work, content and good humoured. For a child the station routine was idyllic.

With the outbreak of war and the departure of her brothers for boarding school, Jill was left alone with her parents. These were the years that schooled her in the bush ethos of stoicism in the face of loneliness and hardship, when she saw that ‘daily life demonstrated beyond doubt that the universe was hostile’. They were the years that broke her father, who was to die trying to connect a pump in one of the half-drained dams.

His death warped her mother’s strong-willed courage into stoical despair. It took a year to persuade her to appoint a manager at Coorain and move to Sydney. By then, writes Jill Ker Conway, ‘I had lost my sense of trust in a benign providence, and feared the fates.’ Over the next fifteen years, especially after the death of her eldest brother Bob in a car accident, her mother’s tragedy deepened, threatening to ruin her daughter’s life too. What saved Jill was a love affair with an American, a man who could see no virtue in her family’s life-denying stoicism. She began to question the world-view she had acquired as a child at Coorain, eventually deciding she ‘wasn’t nearly tough enough to stay around in an emotional climate more desolate than any drought I’d ever seen’. By then a lecturer in the history department at Sydney University, she felt that as a woman academic she had come to an intellectual dead end in Australia, the cultural values of which she now rejected. Instead, she looked for an escape to a more congenial emotional climate ‘where ideas and feelings completed rather than denied one another’: hence the United States and Harvard.

The Road from Coorain is a journey many expatriate Australians made in the 1950s and 1960s. Nearly thirty years on, most of us would like to believe that we live in a less desolate intellectual and emotional climate, but who would deny that our dominant myths continue to glorify stoicism and failure, to regard nature as cruel and harsh, and to perpetuate the conviction that the pursuit of happiness is doomed to end in catastrophe?

Jill Ker Conway’s fine honest book deserves to be widely read in her homeland; it is one that our mythmakers – especially our writers and film-makers – should take to heart.

Comments powered by CComment