- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In the title story of Kerryn Goldsworthy’s impressive first collection, a man and a woman are travelling inland from the city towards the point where main roads give way to obscure tracks. Their relationship is failing, though they have yet to admit this to each other.

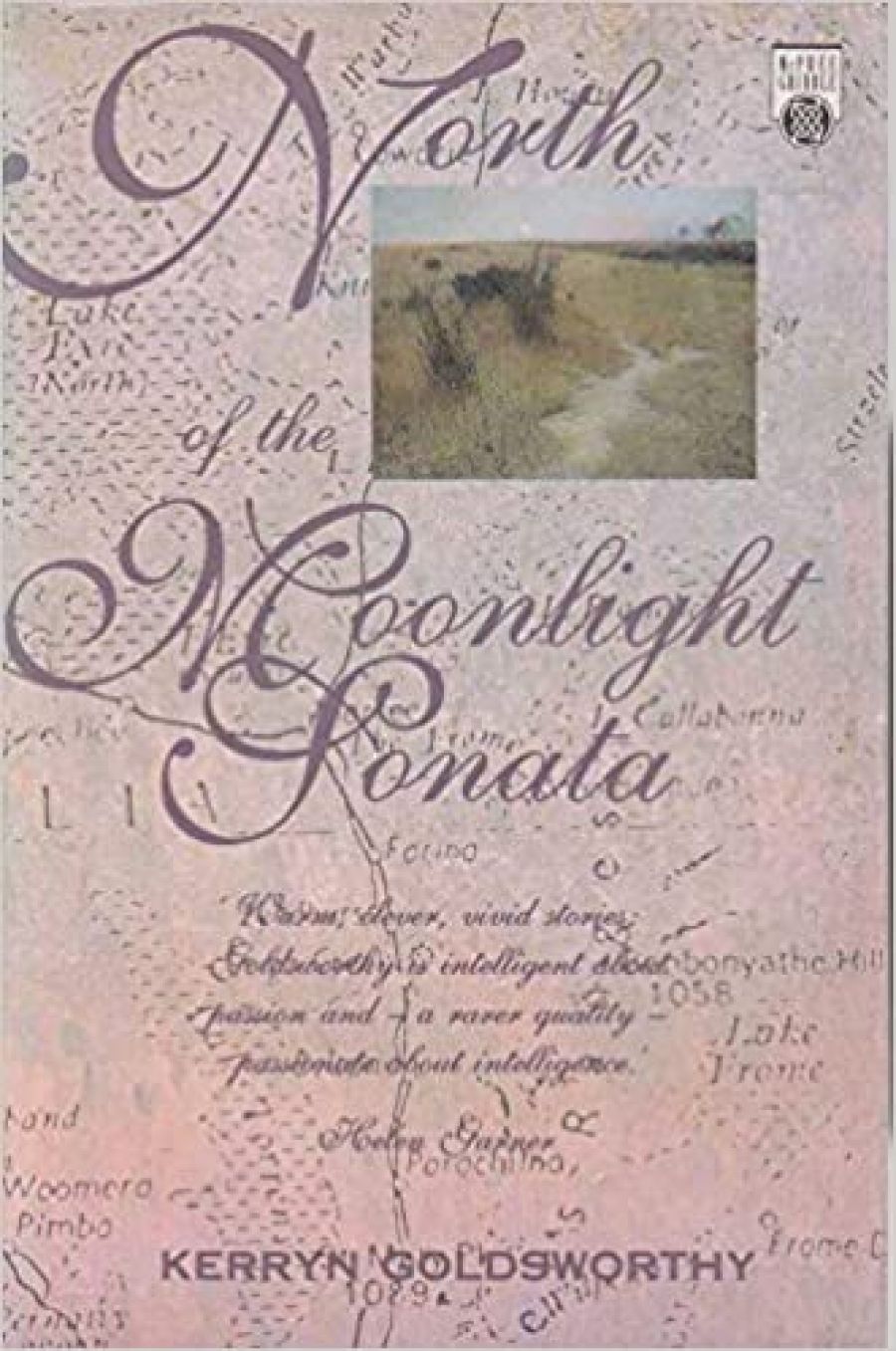

- Book 1 Title: North of the Moonlight Sonata

- Book 1 Biblio: McPhee Gribble, 147 pp, $11.99 pb

- Book 2 Title: The House Tibet

- Book 2 Biblio: McPhee Gribble, 345 pp, $12.99 pb

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

- Book 2 Cover Path (no longer required): images/1_Meta/April_2020/81P6myYc4XL.jpg

‘North of the Moonlight Sonata’, declares the back-cover blurb of this book, ‘is unmapped terrain’. These stories venture into those ‘great trackless deserts of feeling and experience’, where expression is forced to be indirect and illusions are systematically dismantled. Goldsworthy’s range of subject and method is extraordinary. Auden’s poem ‘In Praise of Limestone’, with its images of impermanence and constant revision, becomes the starting point for the rewriting of family history. The lyrics of country music, the rituals of psychodrama, lend themselves to startling climaxes in personal relationships. In the hilarious satire, ‘A Patron of the Arts’, seven letters and an invoice expose academic stuffiness and creative mischief with the help of tomatoes, a lemon and a desecrated pot plant. The teenage memoir, ‘Teach Me to Dance’, contains a beautifully controlled double epiphany which frees both story and narrator from misplaced sentiment and ordinariness.

In the long story ‘The Network’, in my opinion the best of the collection, Goldsworthy dwells on the wishful reading of words or images occasioned by love, doubt or desire. Her writing here, as in the rest of the volume, delights with its economy and inventiveness:

She took his hand and put it to her mouth. Salt, champagne, her own sharp smell, his fainter one. He felt the point of her tongue in the middle of his palm, and little electric messages went zapping down the wires.

‘What are you doing, exactly?’

‘Reading your palm.’

He wondered if Victoria Bailey [a novelist] would call this a passionate act of reading.

That unforgettable image, overthrowing received meanings, suggests the pleasures offered by this book: refreshing insights, evocations of the intangible and, above all, liberating wit and humour.

While Kerryn Goldsworthy’s stories venture into strange territory, Georgia Savage’s latest novel is reassuringly familiar. This may seem a strange thing to say about a work whose subject is ‘incest and its aftermath’, but in fact this fiction relies heavily on old formulae, in particular the bildungsroman and the picaresque tale.

Thirteen-year-old Victoria Ferguson is the victim and protagonist. She lives in suburban Melbourne with her parents and brother. Dad is a demanding and ambitious architect, Mum is a potter who has ceased to practise her craft because her husband casts constant aspersions on her talent. After a violent fight one evening, Mum leaves home and Dad performs the ghastly deed while Victoria is in the middle of trying on a party dress.

Victoria tries to take refuge, firstly with her grandmother, who refuses to take in the gravity of her allegations, later with Aunt Penelope, who calls herself a ‘feminist’ and is in the middle of a drunken lurch with a famous author at the crucial time. The plot unfolds with the inevitable precision of a case study.

Victoria and James, who insists on tagging along, head for Surfers Paradise, where a series of happy accidents draws them into a circle of other youthful runaways. To mark their changed circumstances, Victoria begins to call herself ‘Morgan le Fay Christie’. James becomes ‘J-Max’.

Surprisingly, this symbolic change of identity doesn’t lead to more fundamental shifts in experience. Morgan’s new world has a very familiar value system. Her best friend Marcelle wants nothing more than to have her photograph appear in Vogue. Allie, outwardly tough, entertains dreams of joining a theatre company. The group’s metaphors for threatening mysteries are strikingly domestic; sex is ‘like having a nuclear bomb in the rubbish bin at the back door’. Homelessness, it would seem, needn’t mean alienation.

After a series of adventures involving a yacht, a brothel, and sudden death, Morgan and J-Max find a home in the house called Tibet (‘because all the wind hit it’). They are taken in by Xam, who introduces Morgan to the wisdom of Jung and an academic view of incest. In time, Morgan’s new-found self-assurance provokes her father’s near repentance and a ‘flood of creativity’ in her mother who plans ‘to represent mythic figures from the female psyche’.

The House Tibet is fluent and entertaining, presenting a comfortable view of the adolescent persona. Most of the characterisation is encoded: in the use of italics throughout the text to denote eyebrow-raising emphases, in the unfaltering use of metric measurements. (Post-adolescent readers may find it difficult, as I did, to envisage what a fifteen centimetre heel looks like without recourse to a ruler.)

Details aside, the central theme is centuries old – the reintegration into society of its unfortunate castoffs. The breathless resolutions of the final chapters reminded me of an earlier novel which featured the sentence, ‘Reader, he married me’. In imaginative scope The House Tibet is a worthy successor to Jane Eyre, but modem readers may find it easier to believe that there is a Mr Rochester at the end of the road for every malnourished charity school pupil than to accept that a sexually abused street-child of our times will find the sanctuary of a house like ‘Tibet’.

Comments powered by CComment