- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Barbara Hanrahan has made her own the ostensibly artless narrative of simple women. Monologue might be a better word than narrative; the idea of a speaking voice is important. ‘I was born in a war, I grew up in a war, and there was war all along’ is how this one begins. It’s the Japanese War in China, the country is occupied, food is short, rice must be queued for. ‘And if the queue didn’t disappear, the Japanese up above would come to the windows and bring out the chamber pots and pour down all their terrible peeing.’ It’s a harsh world to be growing up in, but there’s a matter-of-factness in the way it’s talked about. ‘War’s war forever, until it ends.’ Or starts again. The end of this war is the beginning of the next; the communists come, one kind of oppression replaces another.

- Book 1 Title: Flawless Jade

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, $29.95 hb

Like Annie Magdalen and Chelsea Girl, Wing-yee tells her own story in her own language, her own idiosyncratic vernacular. She perceives a great deal although she understands almost nothing but hard work, suffering, and her own impotence, as a child, as a woman, as a Chinese caught up in historical events at home and in Hong Kong. The child’s-eye view of history – ‘They said it was Victory and then we learnt to sing Victory songs’ – offers to the reader a quite different level of understanding from that of the narrator: she constantly tells us far more than she knows. It’s as though Hanrahan is trying for limpidity, a transparent medium through which the real nature of the matter can shine.

Of course all this naïveté and apparent artlessness are highly wrought, the product of a very careful art. It begins with choices. Wing-yee’s random narration of the events of her life from birth to womanhood, in mostly short sections with names like ‘The Seventeenth Child’, ‘Sexy’, ‘Stronger than Perfume’ (which sometimes seem quite arbitrary and even surprising but should be taken notice of), iterates certain themes. A major one is women’s lives and the values put upon them. I wondered if maybe this was why Hanrahan chose the Chinese setting, because of its notorious misprizing of girls. This is spelt out from the opening page: ‘I was the third girl so I wasn’t welcomed.’ Her inferiority is taken for granted. The best she can hope to be is an object of use or ornament for the men she must serve. And even her ornamental value is a matter of obedience to strict rules, like not having too large a mouth; it should resemble a heart-shaped plum. The nose should be like a drop of water, and the complexion pink and white. Big Sister works in a brassiere factory, ‘sewing foam rubber into brassieres, to give hidden glamour to ladies’ beauty zones’.

Foot-binding, as you’d expect, is an ugly presence; her grandmother was ‘a ladylike person with bound lotus feet who walked tiptoed, like limping’, though her mother seems to have escaped this fate by her own efforts, cutting off her bandages and throwing them away whenever they were sewn back on. Her family was once ‘high-to-do’, civil servants close to the emperor, whose fortunes declined because they had no sons to inherit, with only scattered pieces of jewellery, fast disappearing, to recall their prosperity. Her wedding was of the Western kind, not the traditional red wedding, which Wing-yee describes, concluding:

And Second grandmother said how in the old time in her village you married a daughter away, and if she’d been a virgin she was given a roasted piglet by her husband’s mother to give her own family. If she hadn’t been a virgin there’d be no red roast piglet and she’d probably be sent back where she came from. And if she ran away from her husband with a lover she’d be dumped in the river in a cage.

Life is governed by lore and superstition – never walk under women’s underpants hanging on a line, dirty ones keep evil spirits away (dirty underpants are something of a fetish with Hanrahan) – which are embodied in stories, and by traditions which involve the performing of rituals, as at funerals, or New Year, when luck is courted. There are a great many pitfalls to be avoided; no doubt they make the bad luck that comes comprehensible.

I’ve said that Hanrahan seems to be trying to achieve a transparent medium of storytelling. Yet her surfaces are rich too. I’ve used quotations in this review because they give the feel of the book much better than I can describe it. They show how the simple speech of Wing-yee builds strong poetic rhythms, with occasionally an endearing clumsiness; a kind of toughness-with-fragility typical of the girl herself. There are marvellous lists; long complicated sensuous ones like the street sellers, food vendors, and service offerers, and comical ones:

it was sexy to have a nylon two-way stretch girdle, a see-through boudoir nightgown, Black Magic net lingerie, Atom Bomb perfume, Sweetheart soap, forbiddm Fruit lipstick, Hollywood Jungle Savage nail polish, a Venus bust improver.

Like most of her comedy, it involves ironic social comment. Some lists are poignant in their context; the embroidery, for instance:

… cracked-ice and fish-scale and lace-like patterns … leaf shapes with Pekingese stitch that was done with two needles … leaf veins and the tails of dragons and the tops of waves with stem stitch.

It’s an art, a skill; at New Year, when they were small children, they ‘floated a needle in a basin of water to tell by its shadow if we’d be good at embroidery or not’. But it’s also a source of sweated labour, which in turn gives rise to horror stories, as when Wing-yee, still a child, spends a week embroidering the front of a shirt, and Little Brother spills a bottle of ink on it. Then she has to do handkerchief embroidery until she saves enough money to pay for the spoilt material.

As well as an affection for objects a theme of naming runs though the novel. Big Grandmother tells her the long list of glorious names of the Empress Dowager. Holy Mother, Glorious and Happy, Grave and Sincere … nine in all. ‘But the Empress Dowager made everybody address her as Dear Father because she’d always wanted to be a man.’ Wingyee is originally called Jin-tai, meaning To Take a Brother’s Place, but her mother changes this to Jin-yee, To Take Happiness. Then at school she’s teased because this sounds like Frying Fish, so it becomes Wing-yee, Forever Happiness. There’s an array of nicknames as well. Flawless Jade is the name she chooses for herself, and the sad tale attached gives an ironic dimension to its use as the book’s title.

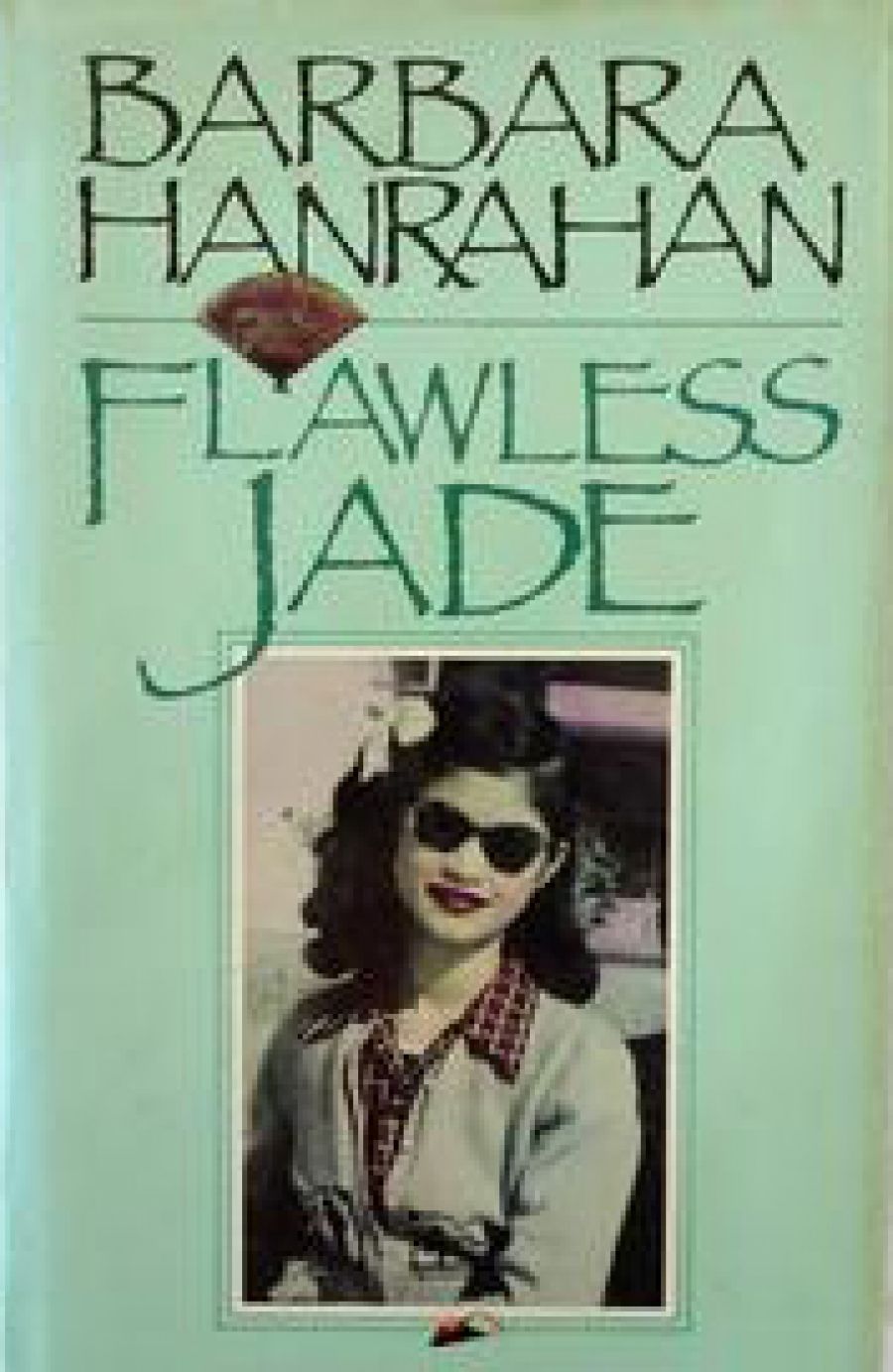

It’s a handsome production, with thick, creamy paper and large, friendly type. I was at first disappointed that the cover illustration wasn’t one of Hanrahan’s own prints, but the strange tinted photographs turn out to have a touching relevance, as well as reinforcing the irony of the title.

What are Barbara Hanrahan’s qualifications for writing a book about the intimate details of a Chinese life? I don’t know, and it doesn’t matter either. Her China is created for us, readers in English; it’s a China of the mind. It enters the imagination through the power of its truth-seeming and that’s what counts.

Comments powered by CComment