- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

The kind of writing that is to be found in Ania Walwicz’s collection Boat is the kind that angers many people. Eschewing punctuation as benevolent and therefore inferior signposts to meaning, Walwicz’s prose is uncompromisingly difficult. Plot is virtually absent. Syntax defies convention. The ugly, both visually and verbally, is preferred to the beautiful.

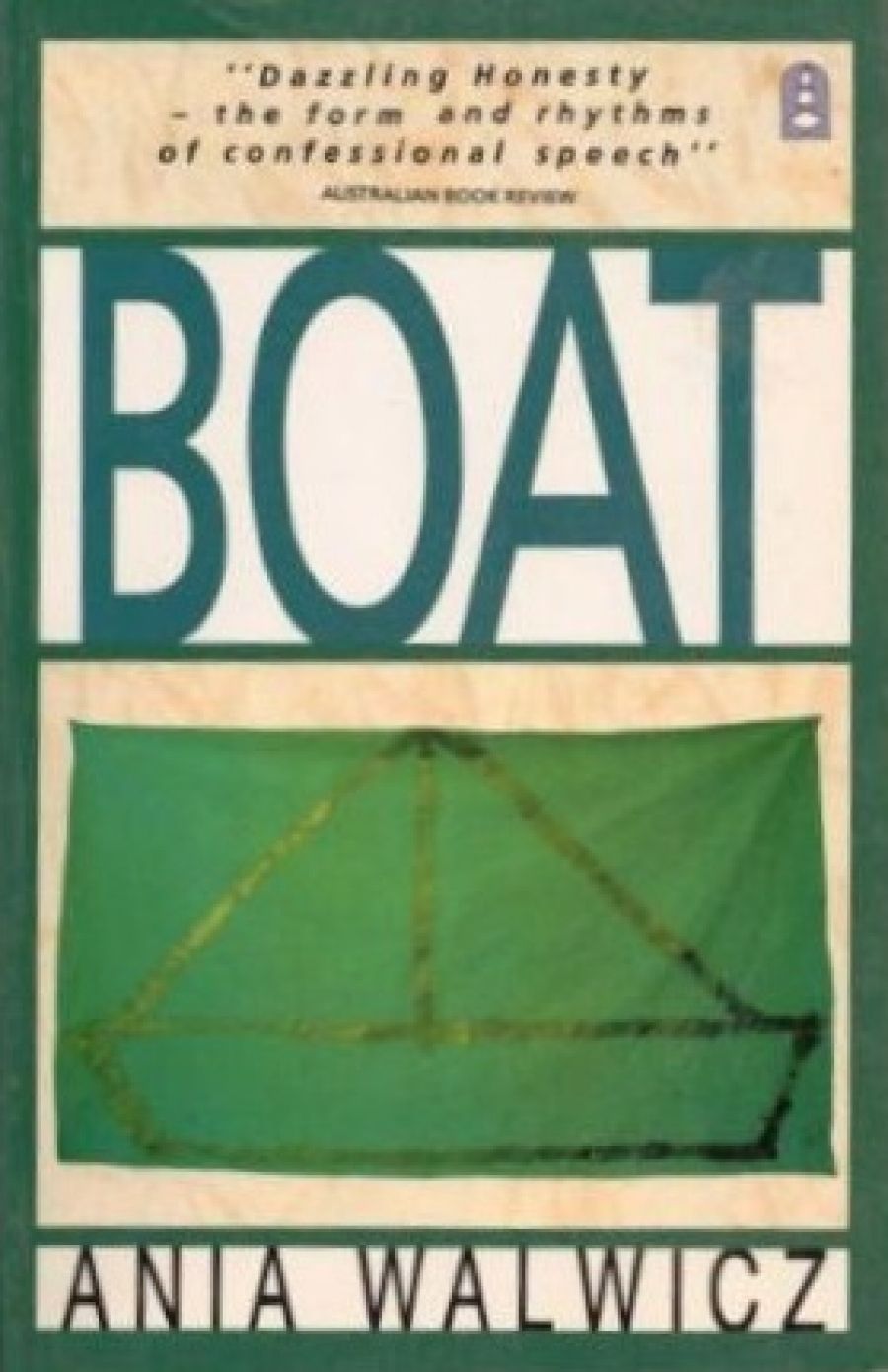

- Book 1 Title: Boat

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus & Robertson/Sirius, $12.99 pb, 266pp, 0-207-16296-4

And so, when Walwicz claims allegiance with such dubious, if brilliant, forefathers, there is cause for caution. However, it is clearly to the tradition of so-called automatic writing that she is turning as well as to the fascination with both the speech patterns of children and the language of dreams. And there is still, after more than half a century of experimentation and discussion of such language, much to be learnt. In Boat, Ania Walwicz guides us a little closer to learning about the deceits and surprises of language.

The cover blurb gives us the author’s own quest principles: to mould personal history into fundamental rhythms of language, to deliberately lay open the processes of thought and feeling, to challenge prevailing perceptions. She often does a lot less than this, which is not surprising as she is a writer who is taking on the whole universe, keen to orchestrate a new, fabulous Babel – Babel wasn’t built in a day. For some of the one hundred pieces, the gaps in information are so wide that only Ania Walwicz, taking great runups and pole-vaulting on her own history, can make it.

This can be frustrating. It’s all very well to demand an effort of the reader, pointing out, in the process, how little effort is required and what ignominious plots can be hatched while the reader lolls passively before an undemanding text. And yet, the great days of limited publishing are well and truly over, at least for a while, so that to expect the kind of devotion it requires to crack some of the puzzles presented by the prose in Boat is perhaps expecting more than a fair share of the reader’s attention. If, as the book’s blurb suggests, the one hundred parts of this spectacular whole are all intricately woven together, to be most effective the whole should be read without too many interruptions, from ‘The Most Beautiful Girl in the World’ to ‘harbour’. Some may relish such discipline, but a meandering path through the book has the appeal of allowing the reader to feel that connections need not be constantly made. To get all that Walwicz is offering requires a huge effort. To get a part is delightfully accessible.

The parts I liked best are the ones that have the accelerating rhythm of an anarchic piece of clockwork, the kind that would defy entropy, the kind that sometimes writers of fairy tales are fascinated by, when the toy cannot wind down and dances on in a merrily frenetic way towards an exhilarating end. In the nightmare vision of ‘wonderful’ or the euphonic precision of ‘buttons’ such a spiralling of energy occurs – best read aloud to enjoy the quite physical pleasure that words employed in this way can bring. Some of the other pieces I’d prefer to hear Ania Walwicz read herself; hearing her read ‘oolee’, a remarkable, witty, and inspired prose translation of a person’s private discussion with a cat puts new meaning into the often quite tedious experience of listening to writer’s read from their own work.

Only occasionally does my anger and impatience rise, when I cannot pick up the rhythms that are behind the voices:

that did not see apart only in what was with me to touch or what did to me you so very very lonely were all one year did not see outs why not come was scared of catching like hanging on threads about breaks so very sorry please forgive myself but yet all time just think abouts you and that returns to and that do so have what a left to be gone ways what …

The refusal to give any cues is certainly an integral part, but it is always frustrating to be left with insufficient information to find the cue yourself. Certainly, this is just as likely to signal a lack on the part of the reader and it’s up to me therefore to decide whether I can live with my deficiency here.

But the keynote to the whole collection is humour. Beyond jokes and irony, the accelerating humour of a piece like ‘playing’ releases a pleasure in language which can only be liberating. It’s the child’s view without pretention and without insincerity (two things which dominated much Surrealist output) that gives the prose its zest:

in they come in don’t step too near they get frightened my airport is waiting little fine made planes come in and land careful now they land they people step out carrying tiny ant suitcases they walk in they land in i made airport for them to come in they came in little plane finger flew in portholes windows seats inside get in and land now

Comments powered by CComment