- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Robert Adamson has as secure a reputation as any poet in this country apart from Les Murray. He rose to prominence in the latter part of the 1960s at the same time as John Tranter, but his affinity was not with the New York poets like John Ashbery and Frank O’Hara, but with the poets of Black Mountain: Charles Olson, Gary Snyder, and, most particularly, with the late Robert Duncan.

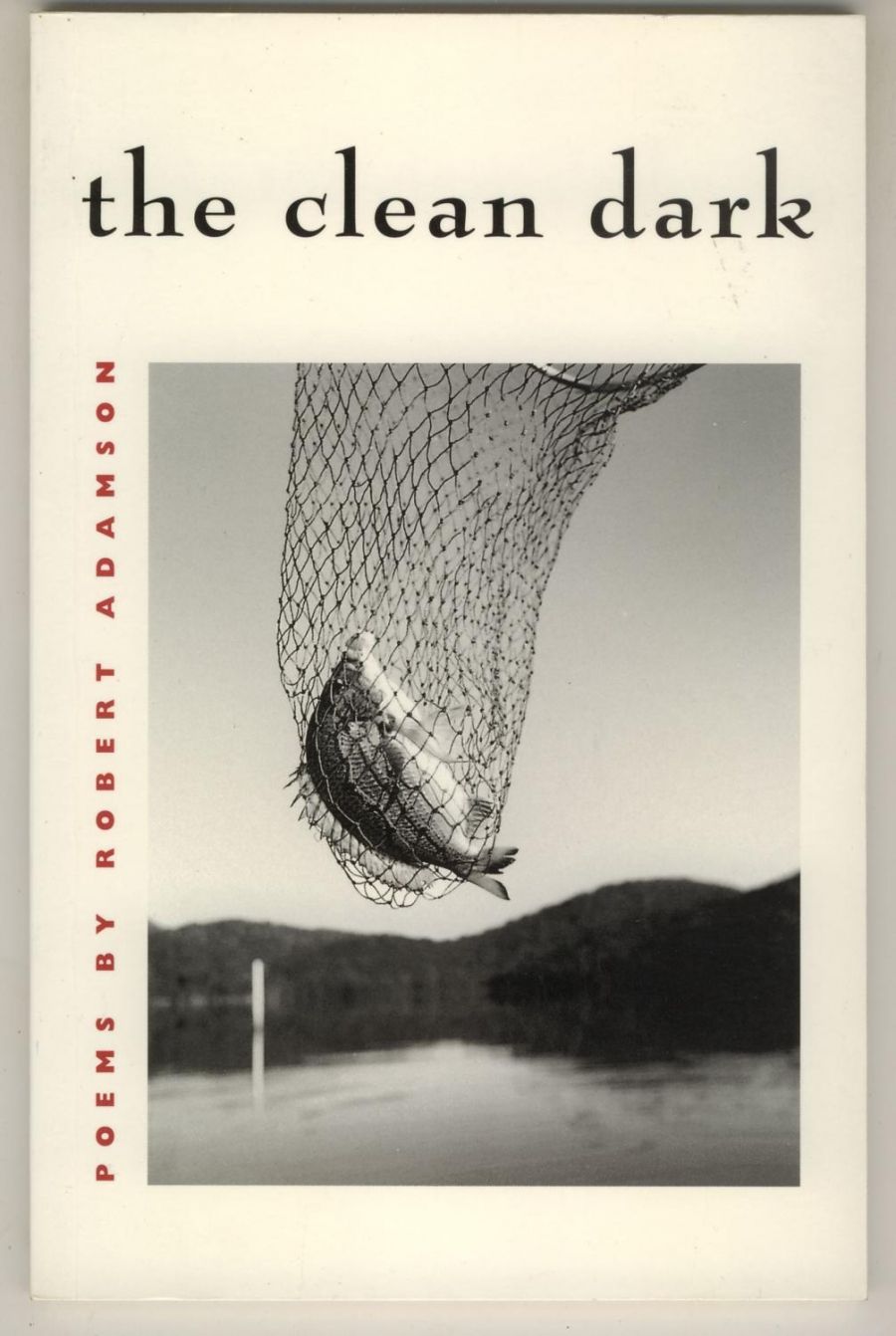

- Book 1 Title: The Clean Dark

- Book 1 Biblio: Paperbark Press, $35 hb, 94 pp, 0958780129

His has always been a poetry of epiphanies in the face of nature, but a nature which was commingled with the play of language across the surface of a physical world apprehended as personal, physical, and violent. Adamson is not a greater poet than Les Murray (and looked at as a verbal ‘essence’, his technique is less gymnastic), but he is, consistently, a poet who blows where the spirit lists. You never feel with Adamson, as you sometimes do with Murray, that a mighty armoury of words is beating down on a piddling poetic subject.

Adamson is alive to a world out there round which the poetry spins webs of passion and apprehension. It seems odd to see him as any heir to an objectivist tradition (he is a long way from the kind of pastoral that Laurie Duggan has purveyed from time to time), but one of the achievements of Adamson’s art is to bring alive, with a good deal of dramatic juxtaposition, the creatures and aspects of particular places, most particularly the Hawksbury River and the seething world of what can be fished up or fixed upon. Such places appear both as a literal object of contemplation and as a metaphor for whatever human activity poetry might shape.

Morning before sunrise, sheets of dark

air

hang from nowhere in the sky

no stars there, only here is river.

His line threads through a berly-

trail,

a thread his life. There’s no wind

in the world and darkness a smell

alive

with itself. He flicks

a torch, a paper map Hawksbury River

& district damp, opened out. No

sound

but a black chuckle …

The poem has an image of the prawns ‘peeled alive’ and all his poetry tends, if residually, towards the same tang and the cruelty – the sense of stoicism in the face of a sensuality half-willed and half-appalling.

This is the lyrical side of Adamson – the poet as romantic, still surviving with more than a touch of Rimbaud and Bob Dylan-ish insouciance. It survives in this mature book as a trace element in the subjects touched on, though The Clean Dark is a characteristically meditative book with little cloak trailing.

What should be clear from these lines is the effect of stillness, the unobtrusive music of things as they can be imagined – the characteristic of Adamson’s rich, dark palette.

The Clean Dark is as good a book of poetry as we have seen in ages. It has sweep without portent and colour without vulgarity. It also escapes from the embroidered artiness, the sense of ‘look what I can do when I play with words’ that enfeebles too much of our poetry, whether academic or streetwise.

Adamson is as good as any poet in our history at creating for himself an adequate symbology. He has created a poetic landscape that is his own and no other’s in such a way, and with such a degree of reality, that it is impossible to say which gets primacy in the mind’s eye: the image that is shaped and fleshed, or the words that configure it.

If words alone are certain good, Adamson’s is a verbal craft which spends part of its considerable energy presenting its excitements as something more than formal occasions.

This is especially remarkable in the sonnets which lament the death of Adamson’s poetic hero, Robert Duncan, because here the language is austerely formal and conjures the feeling that one must walk to the beat of a drum roll which is also an obsequy:

Now Duncan’s death succeeds more

than most, his life opened days, bought song to nights where silence riddled prayer.

it is not enough to weave more silk

No, the spinning silk is not enough, but Adamson’s ability to capture the gravity of feeling from adaptions of language (that might as well be original) make him one of the highest poetic presences of his generation.

He is a ‘presence’ as sure as – indeed more sure than – Murray.

The ‘egotistical sublime’ is not the only way to write poetry, and in the late twentieth century it may seem a distinctively risky way, but Robert Adamson’s brand of late Romanticism has been tested against the pulse. It breathes like the things it speaks of.

This is a book that deploys poetic skill with no apparent effort, which summons its passions as a dancer deploys steps. It deserves the attention of whatever reading public has ever cared about patterns of words and the feelings they can conjure.

Comments powered by CComment