- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Elizabeth Riddell quipped about Kevin Brophy’s first novel, Getting Away With It (Wildgrass, 1982), that he hadn’t! I do not recall anything else of her review, but must confess that it also replaced my own estimation of the book. With hindsight, it’s clear that the novel has too many attributes to be disqualified, however wittily. Furthermore, Brophy’s new novel, Visions, recovers the best of his earlier novel’s operations, advancing them this time in an entirely coherent and often marvellous manner.

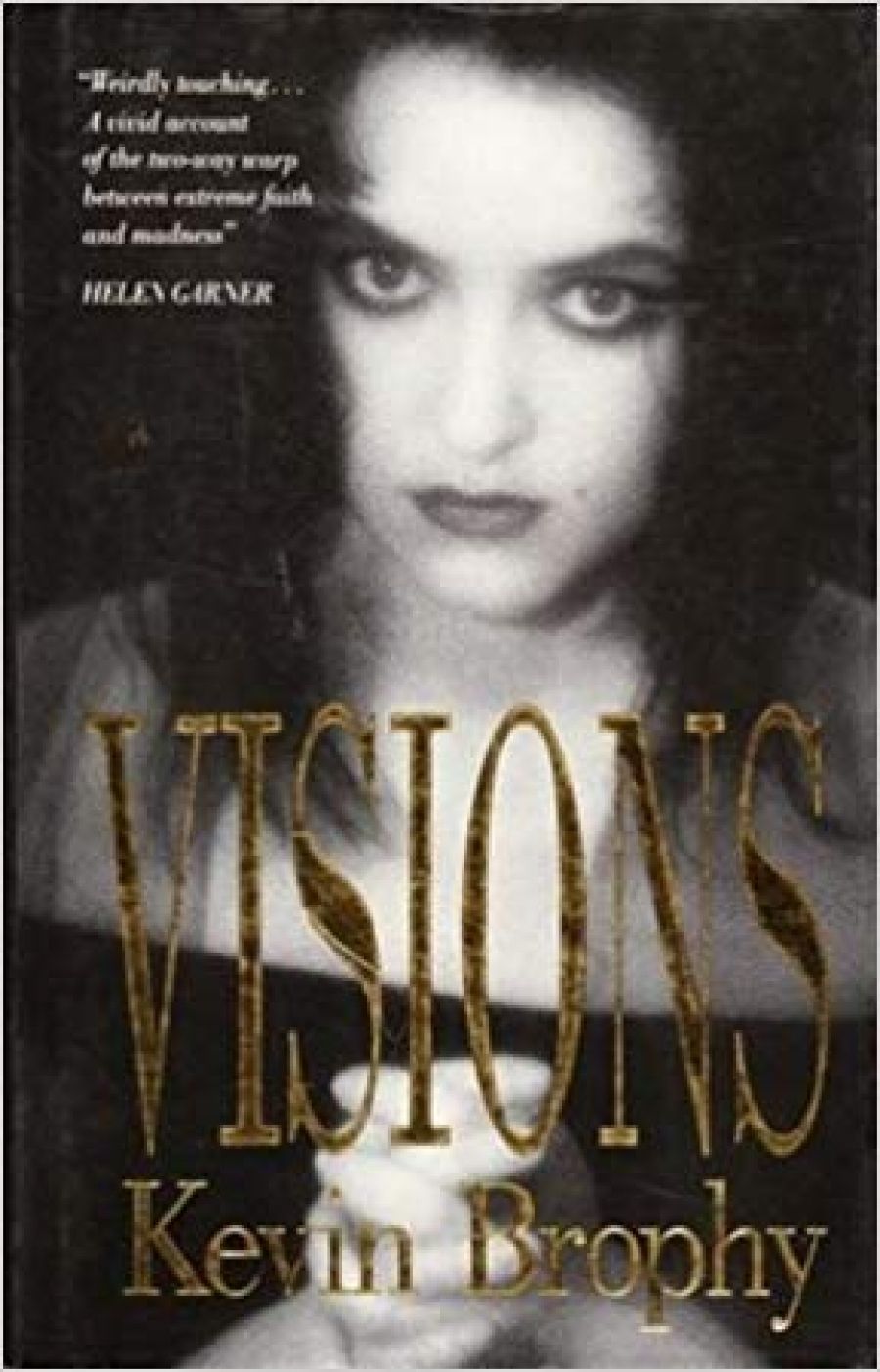

- Book 1 Title: Visions

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus & Robertson, $24.95 hb, 177 pp

The estrangement which abounds in Getting Away With It does deeper than a country boy’s first encounter with the city, though the city as a miasma is certainly one of poet-novelist Brophy’s airs. The country boy confesses: ‘Once again I go over the sins of my life … If my sins are too immature the priest won’t take me seriously … ‘ But it is the ‘sin’ of ordinariness – the existential limitation – that weighs on the character and indeed, substantiates him: ‘This life is not good for me. I think I need a change …’

His delinquent companion Mary ‘knows too much about Saints’.

For example: ‘St Gertrude, virgin. 14th century, entered an abbey at the age of five. By the time she was twenty-five she was having visions.’

Mary is the one character to survive the journalistic serendipity of Getting Away With It. She is the source for Margaret, the narrator of Visions, and a wonderfully liberating persona for Brophy.

There are stranger events than those to be found in Visions, recalled in Gombrowicz’s weird tale, Cosmos, which really is a cosmology, although the peculiarities of his youthful protagonists offer madness and paranoia as the key to what’s unravelled. Brophy shares with Gombrowicz the use of strangeness and estrangement as the mode by which meaning or sense is made. Gombrowicz’s narrator asks:

Can nothing ever be described as it really was, reconstituted in its anonymous actuality’! Will no one ever be able to reproduce the incoherence of the living moment at its moment of birth.’ Born as we are out of chaos, why can we never establish contact with it?

Gombrowicz calls for experience and not explanation: ‘No sooner do we look at it than order, pattern, shape is born under our eyes. Never mind. Let it pass.’

Brophy’s great success in this fiction is to elude explanation. The first-person narrative is perfect for the artifice of unmediated contact with experience. Only slightly, at the end, does the great Australian inability to distinguish between character and caricature infringe upon the novel’s integrity.

Visions reminds me of one of Marquez’s most memorable stories, ‘The Incredible and Sad Tale of lnnocent Erendira and her Heartless Grandmother’. Brophy’s Margaret is a first cousin of Marquez’s Erendira. One’s natural response to both of them is of sympathy for the innocent whom one identifies as the victim. In secular societies innocence has no other status. However, if the story is mythical, then the natural(istic) response is beside the point, for as far as innocence is concerned, it does not tally with victimisation. Erendira’s ‘misfortune’ is the objective reality and not merely a character’s point of view. Myth’s irrevocability itself provides status. Like Marquez’s enslaved granddaughter, Margaret the would-be saint is the vector for a particular course of events. She makes the world what it is.

Margaret’s testament allows the reader to construct a life story, perhaps even of the same duration as Erendira’s years of misfortune, from the precocious twelve-year-old to the somewhat world-weary young wife, the equal of any normal authority since neither family nor church could ever subdue the prepossessed consort of God. The narrative enables both a literal reading, wherein the child deals with her mysterious father’s absence through a succession of male explicators, accumulating a compensation of the ultimate magnitude, as well as an imaginative one in which causality is a trivialisation of the life divine. As Margaret says, after her expulsion from Mother Therese’s convent: ‘She said she understood that I’d been touched by certain experiences. I think they are experiences she has hoped for all her life.’

It could be said that this is the dialectic of Brophy’s novel.

Stylistically, the poetry in the text is maintained by the direct syntax of Margaret’s confession. Quite aside from whatever story the reader makes of the novel, there is the pleasure of Brophy’s figures and imagery. For example: ‘Sister Mary ... is a desert, if a desert could be a nun ... ‘; ‘My mother’s words are small round pools on the floor’; ‘The bread shines like sand’; ‘I was a feather, I was a great distance, a feather to float’; ‘The world, not thinking of itself strangely enough, disappears, and in its place is this fog.’ This last sentence quoted is, more or less, the mystical dictum.

In this telling of Margaret’s, the narrator’s ‘secret notebooks’ are mentioned, though never quoted. She is probably beside herself as she tells all this. The reader is, insatiably, alongside her – like a shadow.

Comments powered by CComment