- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Elizabeth Jolley’s new novel takes a leap into the past, to a large hospital in wartime England where Veronica Wright, an awkward girl just out of a Quaker boarding school, endures the discomforts and humiliations of a trainee nurse. As we have come to expect from this writer, there are all sorts of marvellous things tucked away in odd corners. Sharp observations of hospital routine – preparing bread and butter for the patients’ trays, chasing cockroaches with steel knitting-needles, shivering on night duty, and trying to keep warm in old army blankets – are mixed with passages of grotesque comedy, and with one or two memorable instances of the macabre, nowhere more effectively than in the death of a gangrene-ridden, maggot-infested patient.

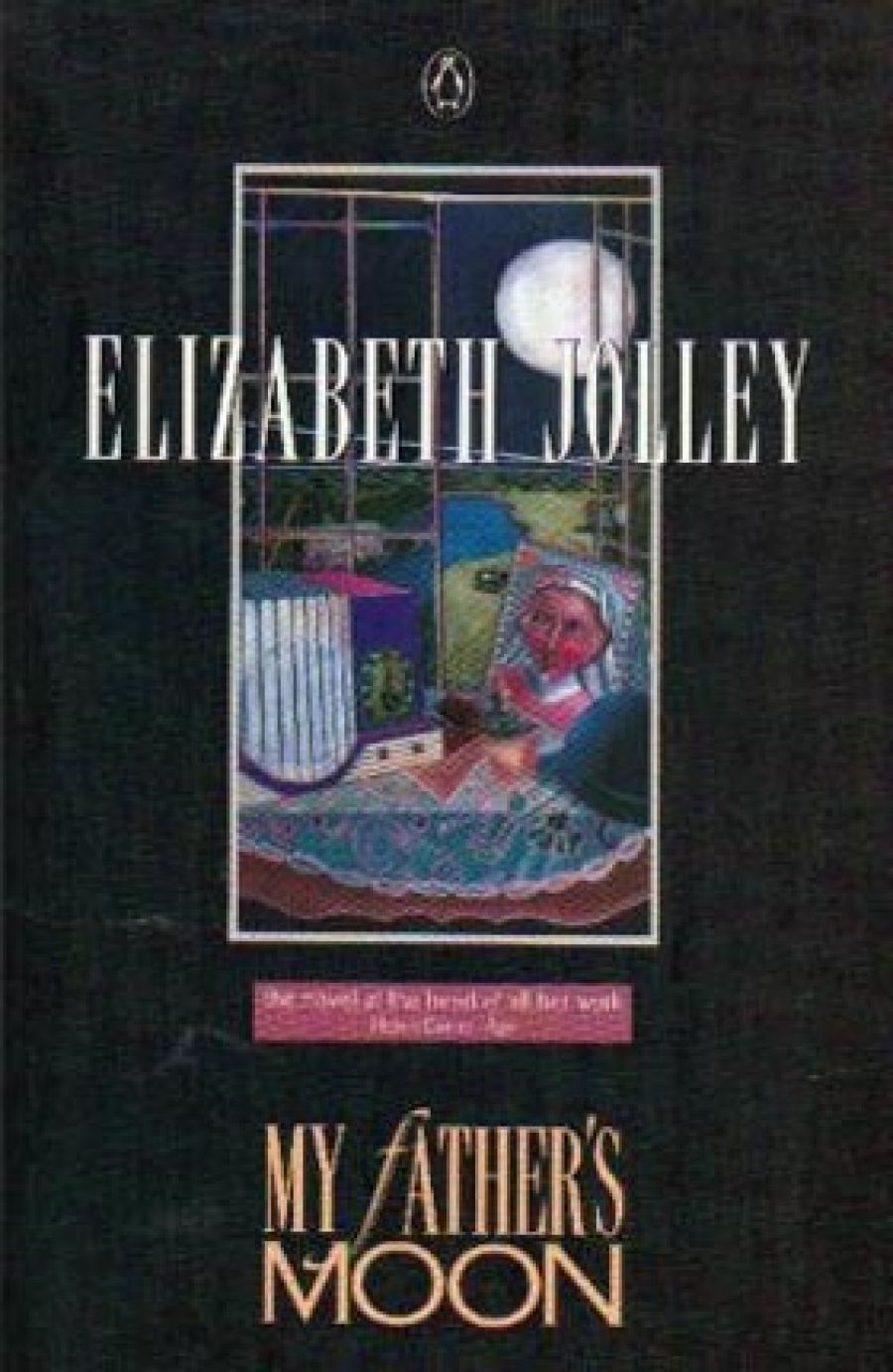

- Book 1 Title: My Father’s Moon

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $22.95 hb, 171 pp

Beyond the hospital walls, we catch glimpses of other nooks and crannies of Jolley’s characteristic world: the headmistress of a progressive school who is never to be disturbed when sharing the bathroom with her deputy; a diminutive refugee from Hitler’s Germany, unable to control her monatsfluss, leaving bloodstains wherever she walks on her clicking high heels. Such images are etched with clarity and economy, with an often shrewd understanding of the quirks of human behaviour.

But they do not add up to a satisfactory novel. Finding an appropriate form has always been a difficulty for Jolley. She is by nature a miniaturist – able to capture the telling moment, the significant gesture or the revealing glance. Extended narratives which develop characters and relationships have never been her forte. For that reason, the fashionable post-modernist novel has been something of a godsend to her. Her wry, bemused, at times quite waspish vignettes of eccentric characters have found congenial homes in the jerky progression and narrative dislocations of her much-admired books. I am convinced that this is why she is so attracted to confined places for her settings: institutions, remote farmhouses or, as in Milk and Honey, a place where the inhabitants themselves erect invisible but impenetrable barriers. For her characters to step beyond these enclosures is often dangerous, just as it is dangerous for the novels to stray too much into the world at large. Once you leave the old-age home, the isolated school or farmhouse, you are likely to come into collision with a world where things happen, where events have consequences.

My Father’s Moon, much more than Jolley’s earlier books, is forced to leave the institutional world of the hospital where, in the confinement of a restricted, mostly female society, people may be depicted as leading a life which is to a large extent abnormal, a life, moreover, where human relationships and the laws of cause and effect are very different from those in the outside world. Whenever Nurse Wright leaves the artificial world of St Cuthberts, she and the novel are equally in peril.

Her peril is rather novelettish. She agonises a great deal about her awkwardness, her poverty and lack of sophistication, about her sense of inferiority whenever she comes into contact with the elaborate rituals of the British caste system. The world is hostile and menacing. Elsewhere the peril is more immediate: she is seduced, in every sense, by Dr Metcalf, the senior surgeon, and by Magda, Metcalf’s somewhat unconvincing upper-crust wife. Yet, having sorted out the complicated narrative pattern, the reader is left with little more than a fairly commonplace tale of a naïve girl who is seduced by the shabby hospital Lothario and abandoned to her inevitable fate.

There are, in the midst of what is fundamentally sentimental fiction, several puzzles of a properly modish sort: did Dr Metcalf really die in a motor accident, or is Veronica implicated in an elaborate conspiracy that would allow him to escape his responsibilities? Could the woman she sees on a train many years later (in Australia perhaps) possibly be Ramsden, the cultivated middle-aged nurse at St Cuthberts on whom she had such a meekly adoring crush? But it is important to ask what purpose these mystifications and elaborate structural devices serve. Notwithstanding the obvious technical ingenuity, why does a commonplace tale have to be told in such a complex manner? One answer, no doubt, would be to say that the writer strives to transform the mundane into the extraordinary – but that patently does not happen here. There are attempts, it is true, at evocative, emotion-filled writing, but the result is, all too often alas, little more than ‘mooning’ around. Predominantly present-tense narratives with a horror of subordinate clauses have, to say the least, very limited ways of generating emotional intensity. In this instance, such procedures lead to a certain gushing as Nurse Wright remembers the world of the hospital, the warm physical communion with some of her colleagues, or when she recalls her family, her father’s assurances that ‘his’ moon will always shine above her, wherever they might be.

What has gone wrong then? I think that the reason why so much of this book is flat, somnambulistic, why it lacks Jolley’s characteristic verve and gusto, and why, lastly, it has so many passages of mawkishness is that it is a novel of retrospection and reminiscence. The author has returned to the places, sights, and sounds of her youth: the dank Midlands under the pall of wartime blackouts, the fields, spinneys, and woods seen in the misty light of recollection. Because this is the past – because the novelist is not recording immediate, tactile reality – a fog of sentimentality hangs over the book. I kept on thinking of Brief Encounter while I was reading it, and fancied once or twice that I was hearing Rachmaninov.

Comments powered by CComment