- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Australian History

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Professor Mulvaney’s thematic history of encounters between outsiders and Aboriginal Australians is developed through a discussion of events located in specific places. He has selected places which are in the Register of the National Estate (many of which he initially nominated) or are being considered for inclusion. The places, then, are by definition part of Australia’s cultural heritage, and an important focus of the book is to illuminate some of the types of events which have shaped Australian society.

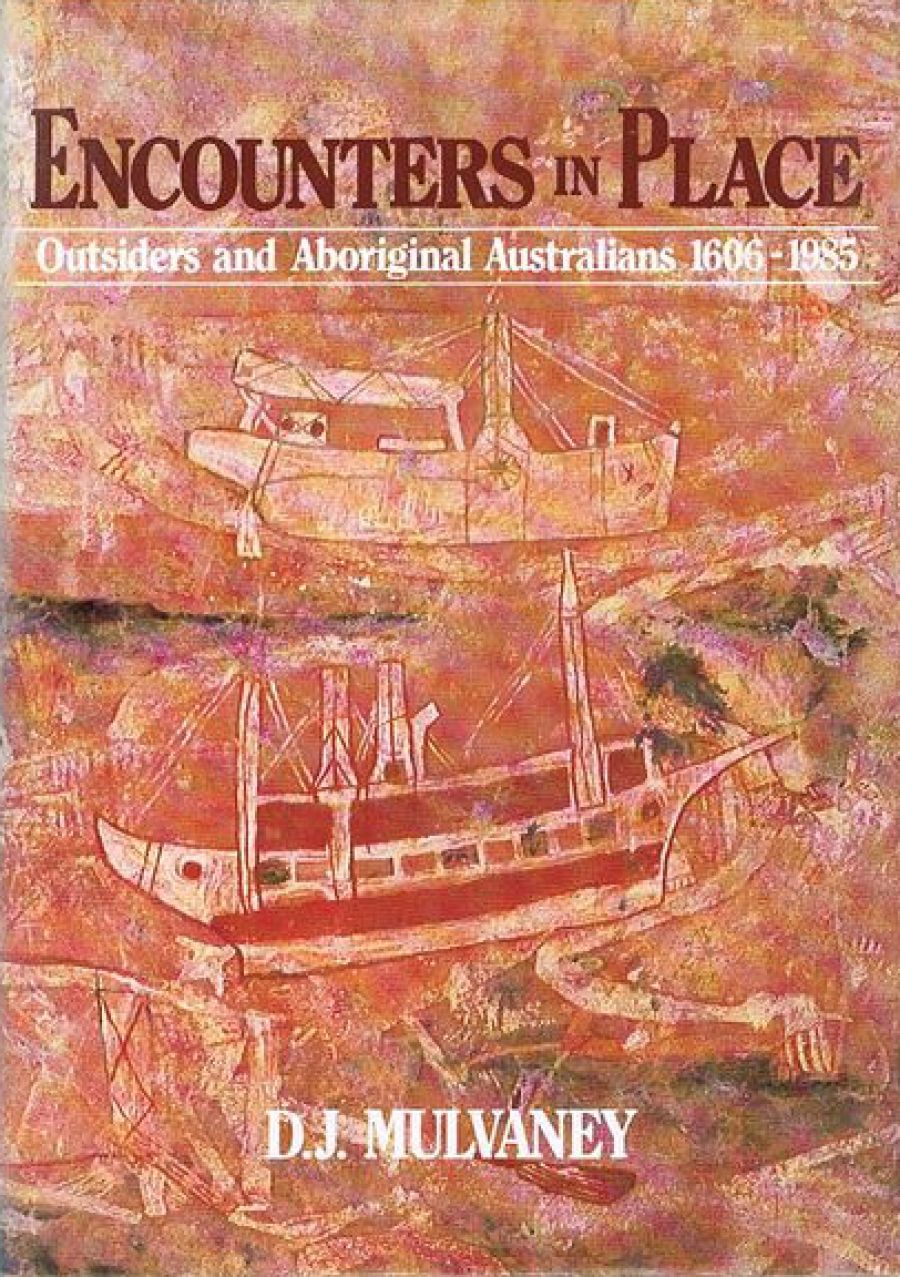

- Book 1 Title: Encounters in Place

- Book 1 Subtitle: Outsiders and Aboriginal Australians

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, 263 pp, $44.95 hb

The emphasis on place might seem inimical to an analysis of processes which, in many instances spanned the continent, but Mulvaney uses the particular as a window opening onto the more general. The chapter on the Cootamundra Domestic Training Home for Aboriginal Girls, for example, includes a general discussion of the practice of removing children from their parents and raising them in institutions. He provides facts, figures and an analysis of ideologies which are not confined to Cootamundra, and he concludes with a brief discussion of the Link-Up organization which helps reunite families which were separated through government policies.

Many of the places Mulvaney discusses are place of cruelty and tragedy. One cannot read of them without a sense of shame. The story of Wybalenna and Oyster Cove tells of how those Tasmanian Aborigines who survived the many massacres (such as the one described in the preceding chapter, ‘Terror at Cape Grim’) were rounded up and moved to special settlements where they were to be protected. Not one person survived the protection. This is also a story of conflicting opinions among Europeans about how to deal with Aboriginal people, a tale of politics and of misguided humanism.

This is a story that is repeated in many, many places. Mulvaney includes enough of them to allow the pattern to emerge. Greed and opportunism are almost invariably opposed to justice and fair play; the result is a political compromise that almost invariably fails to provide equitably for Aboriginal people.

In the chapter on ‘Self-determination at Coranderrk’, Mulvaney provides an excellent treatise on the whole process of confining Aboriginal people to diminishing areas of land (as settlers demanded more land for themselves) while at the same time requiring greater degrees of productivity (and less government expenditure). Such ‘protection’ assured that the extinction, which it was claimed reserves would prevent, would indeed occur. The manipulation of definitions of Aboriginality which was to become a critical means of controlling people’s lives and destinies is clearly shown.

Mulvaney is not an ideologue. His sense of responsibility as a prehistorian and as a historian includes a strong respect for evidence. His style is rather dry but never obscure, and man of his summations are gems. Of Coranderrk, for example, he says:

Despite fine words and promises, therefore, the only permanence which Aboriginal people gained at Coranderrk, are the graves of some 300 people on the hillside overlooking the station.

In addition, he often takes the opportunity, to set the public record straight. The chapter on Cape Kerweer includes a fine section on various folk theories of early ‘discoveries’ in which he assesses the evidence, favouring the demonstrable at the expense of the fanciful.

Mulvaney's words gain force when he deals with families and with invalids. His chapter on the quarantine islands Bernier and Dorre is particularly impassioned. Aborigines who had been diagnosed by policemen and found to have venereal diseases were put in chains and brought into custody to be confined to one of these two islands where they lived, suffered and died:

There is no evidence to suggest that the Aborigines Department questioned its right to treat and isolate Aborigines compulsorily. For individuals who were neither slaves nor convicts, this is a grave indictment of a democratic system.

This assessment is made before Mulvaney discusses a further aspect of treatment: Aboriginal patients were used as involuntary subjects for testing experimental drugs.

Not all the encounters are so grim, and Mulvaney also discusses some of those which worked well. The settlement at Port Essington, for example, puts the lie to ideologies which assert that the cruelty and injustice were an inevitable by-product of EuropeanAboriginal encounters.

In addition to using places as points from which to explore the history of encounters, Mulvaney has a particular message about the preservation of sites of historic significance. ‘A mature Australian culture should identify with these monuments or symbolic sites and conserve them’, he says. His use of the word ‘should’ suggests that he has some doubts about the Australian public’s willingness to engage in remembrances which do not glorify, and seems to single out European members of the public.

Virtually every chapter contains a brief statement of why the place being considered is worthy of inclusion in the Register of the National Estate. For the most part, I found these statements intrusive and unnecessary; the evidence is compelling in its own right. They do, however, allow Mulvaney gradually to develop his statement of what a mature society should be, and it is this understanding which links past and present most forcibly. One of the best statements is in the chapter on Pinjarra and Battle Mountain:

These events occurred over 150 years ago. While time cannot diminish their barbarity, the work of a mature society should be to accept their reality, and to work to establish more harmonious racial relations.

There is a compelling issue here which, because of the structure of the book, emerges only gradually. What happens is that we see the same event being played out over and over again; economic and political aims prevail at the expense of, and in contradiction to, the secular and (formerly) religious values on which this nation is founded. After reading Encounters in Place, we may see an event in the present, such as the encounter between BHP, Aborigines and conservationists at Coronation Hill, as less like a new event and more like the same event happening yet again in yet another place.

Comments powered by CComment