- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

From the very beginning of The Rearrangement the reader is involved in themes which will play repeatedly through the poems: learning, knowledge and memory, and the way in which these work to satisfy, or frustrate, a metaphysical sense of order, even truth.

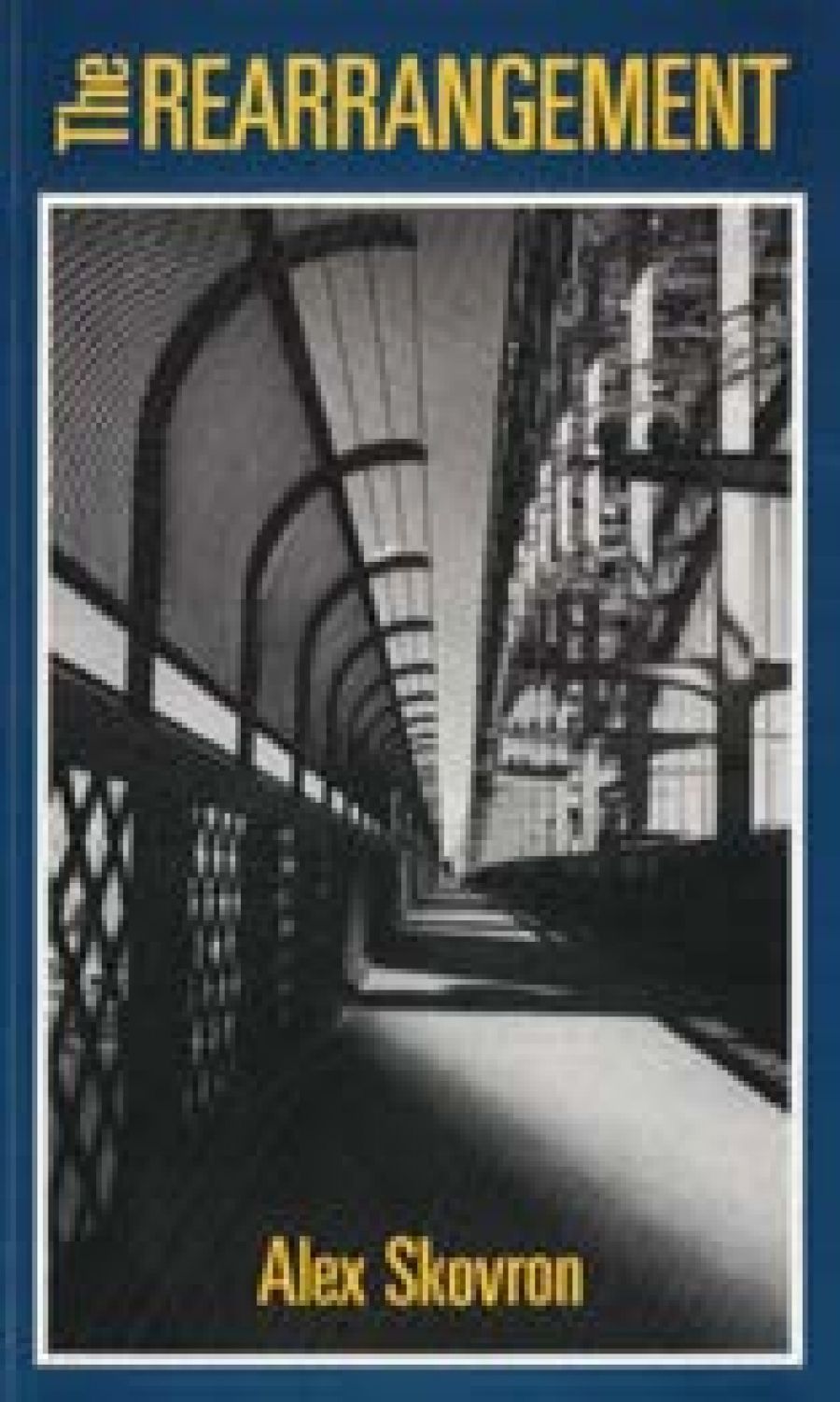

- Book 1 Title: The Rearrangement

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Press, 112 pp, $19.95 hb

The poems are cryptic, highly subjective and full of presence; the intense metaphysical· search beating out through them is hard to ignore. Underlying it all is Skovron’s complex involvement in words and language, both in his own poems and in the crucial world or spirit-place of books:

Collecting my life in books that spine

these cubical perimeters, I scan

the magic-lantern glow from the soft

focus

of a swivelling chair, elbows desked, foot awake, waiting.

There is a rich and strong range of poetry, from the sensual humour of ‘Interview with a Faded Juggler’ through questioning and resonant poems such as ‘Arrival’, to the long eager narrative of ‘Lines from the Horizon’. History, Europe and philosophy are ever-present. Hardly regional, ‘Australia’ occurs here occasionally, but these poems are more of the poet’s intense imagination and almost heady sense of culture.

Skovron was forty when this, his first collection, was published, and it is interesting to wonder how much the strong individuality of the poems is the result of this unusual restraint.

At times perhaps too individual. There is a definite yet paradoxical worry I have over the language use in some of the poems, which are intensely solid in feel, almost sculptural, with shape and weight - but where, for all this undeniable presence, I find no ease, no space, as if their fullest reference or aspect is inturned (interned?). I have the distinct feeling that Skovron uses words as if all are rendered equal, and the proportion that he does not weigh and balance against current placement and usage is too high. So at times his lines sound strongly, but do not speak; at times his syntax is so dense it is granite:

Her fingertips

glibbed unheard symphonies, penless

wrist

fresh from slashdreams drummed rain

dances to Bach

partitas, but no gush swelled to cleanse

under.

And again:

The general – systematic man

at death of day transfixes crimson

melting sun sipping sherry sink into the

bay.

Examples are easy to find in poems like ‘The Choice’ and ‘Finishing Things’, but usually (thankfully) only passages suffer, rather than entire poems. For me, his achievement rests in the highly energetic and often brilliant longer narrative poems such as ‘Lines from the Horizon’, ‘Fugue’ and the extraordinary title poem. This last is a sequence of sixteen sonnets, in the persona of an ageing and obsessive scholar who searches endlessly for order and truth in the study and rearrangement of his extensive collection of books. This character reminded me strongly of Peter Kein in Canetti’s Auto da Fé, and despite a slow start to the poem, this grand and ironical obsession becomes enthrallingly absurdist, a gross Hasidic nightmare!

The best poems are vivid, powerful and humorous, showing little of the frustrating stone-like style I mentioned earlier. The collection closes characteristically:

There are no books in hell.

Only a silence of the rock: coldly

Silently

Tolling.

Comments powered by CComment