- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

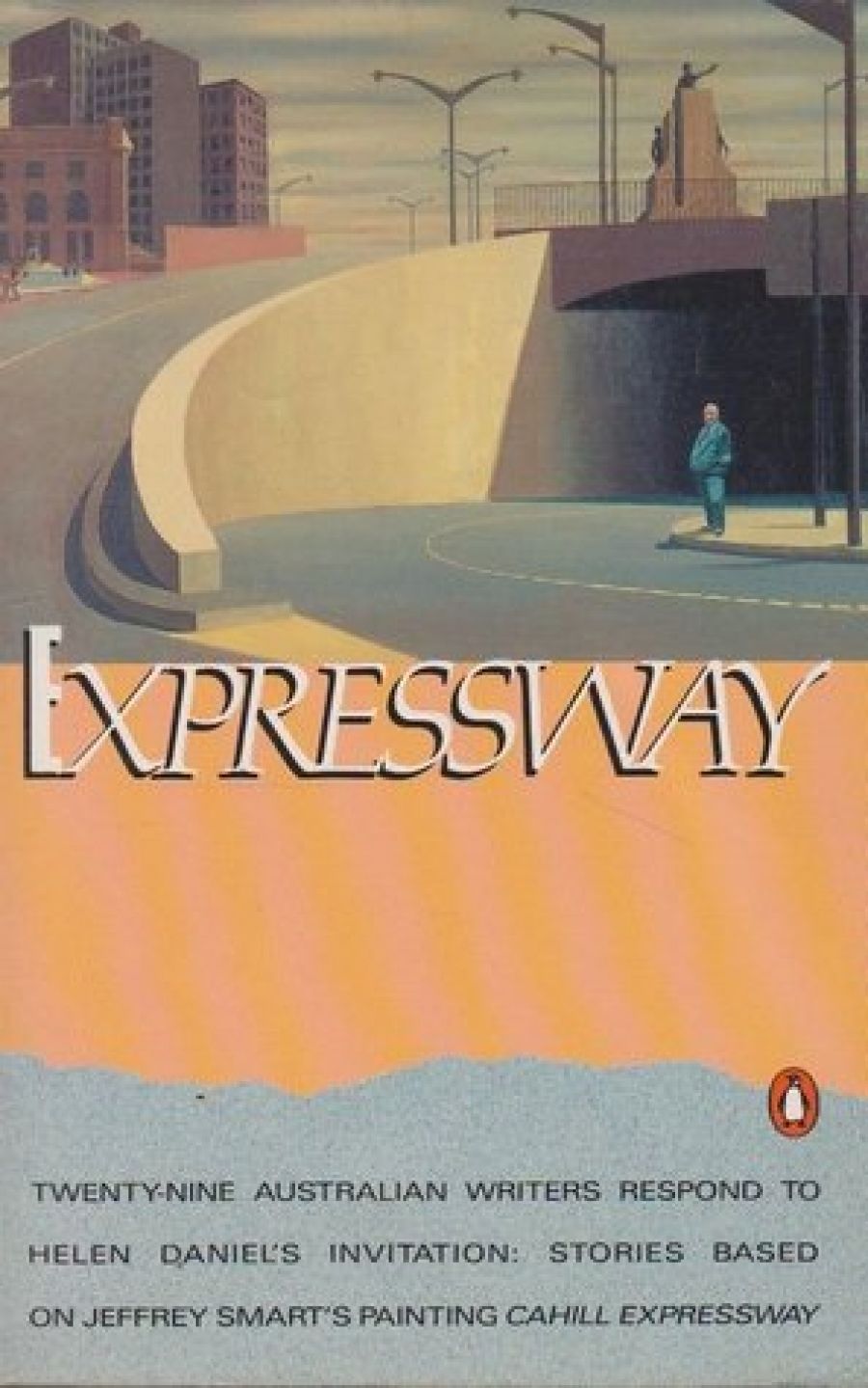

If the proof of the pudding is in the eating, then Helen Daniel came up with a wonderful recipe indeed. Invite thirty-odd prominent Australian fiction writers to respond to Jeffrey Smart’s 1962 oil-on-plywood painting, Cahill Expressway, hung in the National Gallery of Victoria. Some declined, but twenty-nine accepted, and Helen Daniel can take great pride and satisfaction in regarding herself as a ‘privileged host’ indeed. This is truly a magic pudding of a book.

- Book 1 Title: Expressway

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $12.99 pb, 294 pp

To give some idea of the contributors, here is every fifth, taken alphabetically: Glenda Adams, Garry Disher, Barbara Hanrahan, Rod Jones, Peter Mathers, Louis Nowra. For the McCluskys among you, there are twenty men and nine women; there are no ‘ethnic’ or, as Sneja Gunew would insist, ‘migrant’ writers represented; there is one Aboriginal. For the Alistair Fowlers among you, the author of Liars must take pleasure in having just twenty-nine contributors. After all, twenty-nine is a prime number; add the editor herself and you have thirty, which is divisible by three and ten, the numbers of virtue and completion respectively.

Helen Daniel informs us in her introduction that ‘these are all new stories, written specially for this collection’. She also rightly insists that the book is different ‘from most anthologies whose miscellaneous stories are read in a fragmented way’. She then makes a very large and perhaps contestable claim:

Smart’s man in the blue suit is the central character in a collective work, a work which in the most startling and fascinating way has the kind of unity and integrity we would normally associate with a work by a single writer. I recognised that I was looking at a new kind of fiction, perhaps a new literary form or perhaps the renaissance of a very ancient form.

Which leads to this: ‘I recognised that the twenty-nine writers had written not a collection of short stories, but a novel.’

It’s the word ‘novel’ which, it seems to me, should (yes, my normative verb!) sit uneasily at the tip of the pen of the author of Liars. Old-fashioned as it may be – but the ‘novel’ is an old-fashioned form – it is hard to go beyond E. M. Forster’s Aspects of the Novel (1926) for an account of the form. Does Expressway have a central character? Well, yes – the ‘man in the blue suit’; and no – the ‘Man in Black’ in his discursive prose formation is missing. Sometimes this man has attributes; sometimes he seems a man without qualities (and one of the contributors is provoked to cite Musil); and sometimes he resembles no one so much as ‘the little man that wasn’t there’.

‘Yes, oh dear yes, the novel tells a story.’ Does Expressway fulfil Forster’s criterion? Well, sort of. It tells many stories (cf. Don Quixote), but seems to be unified by its field, its unity of place (to invoke Aristotle for a moment; usually no help vis-à-vis the Novel). It is the story of Australia here and now in the consciousness of its writers. (Its ‘non-migrant’ writers, that is.)

It would be much more helpful to disregard the term ‘novel’ here, and regard Expressway as text, as it is characterised by the harmonies and disharmonies, the adjacencies, absences and aporias that may be associated with that notion.

In trying to account for Proust (and I am happy to extend the notion to Modernism at large) Forster invoked musical analogies in a chapter on ‘rhythm’ – his least successful chapter. Remembering Richard Lunn’s story ‘mirrors’, in which the reader was offered the privilege of constructing alternative routes through the numbered fragments of the story, Helen Daniel observes of her collection:

I realised that a policy of [editorial] non-intervention might be best realised through a policy of multiple and contradictory intervention. Reader manumission.

‘Expressway’ is a democratic novel and, for the reader too, it is democratic. The reader has suffrage. At the end of each story, there are ‘freeway’ choices to be made.

Of course, it is Helen Daniel who has constructed the ‘freeway’ signs. And these signs derive from the (Forsterian) analogy of music. They may be reduced to three in direction: Harmony (e.g. descant, counterpoint, fugue); Dissonance (e.g. discord, tempo change); and Encore (e.g. solo, encore). The first two direct the reader elsewhere in the book than to the next story; the third directs the reader outside the book to other books by the contributor, or to other authors – in two wonderful cases, to authors being parodied.

While I confess to reading Expressway from the ‘infant A standing on infant legs’ to ‘twisted, stooping, polymathic Z’ – a choice determined by reading it in page-proofs as much as anything else – I think that Daniel’s highway-signs are at once challenging and enticing. And I’m sure that she would be the first to permit the reader to construct his or her own signs. On the other hand, the signs provided are her signs – and their source in music suggests to me the inappositeness of the ‘novel’ claim – just as the Jeffrey Smart painting is her initiating choice. I think she and the book are at times in some sort of editorial and textual double-bind, which I can best express as two concomitant, inextricable urges, thus:

- the text does give pleasure, as the reader applauds how each individual contributor brings the man in the blue suit into his or her particular fiction.

- the text creates a problem, as the (this) reader feels overdetermined and anxious to see how each successive author brings the man in the blue suit in. Reading any individual story (and this is exacerbated by accretion) becomes rather like en attendant the man in the blue suit. And this cuts across, to some extent, doubtless differently for each reader, the admirable desires for ‘democracy’, ‘suffrage’, ‘manumission’.

What do the contributors see in ‘Cahill Expressway’? What do they create in their acts of interpretation? Many concentrate on the man in blue. Some of them concentrate on his being one-armed, indicated by his pinned-up sleeve, a detail which has escaped inobservant me, as it appears to have David Malouf among others.

Some address his dress, the semiotic of a suit in a democracy – Kate Grenville and David Foster are particularly interesting here. Peter Mathers, in Shandyesque mood, concentrates on the man’s nose. Others concentrate on the tunnel; the light poles (Mudrooroo Narogin is very provocative here); the clouds; the library (Michael Wilding offers an entertaining story à clef here). Finola Moorhead observes that the statuary atop the tunnel was presented to Sydney by a Mr Gullet; Glen Tomasetti captures the human emptiness of Smart’s Sydney by setting her Melbourne story at the National Gallery on Melbourne Cup Day. The delights are endless.

The story/painting relation is more significant in some of the contributions than others. For some, the relation resides in the lack of relation, in negation or absence. Morris Lurie gets everything underway in the first story of the volume:

‘Well I guess it’s a symbol.’

‘Good. Good. Of?’

It appears to this reader, however, that the dominant, the overweening relation between writing and the painting indicated in this volume is that of causality, either as cause or effect. Thus, the stories read the painting by means of biography, as history (individual or cultural), as literary or art criticism (via parody), as eschatology. The dominant species of the causal analogy that suggests itself here is paternity and filiation. (Twenty men, nine women, remember.)

This dominance is underscored by the different ways in which Marion Campbell and Finola Moorhead demur from it. Campbell’s narrator is her father’s amanuensis, he having lost his writing hand (Lacanians may cheer). Moorhead’s feminist perspective is more overt and even funnier. Glen Tomasetti is delicately insidious by staging a mother and daughter, and having the mother prefer other painted versions of Sydney to Smart’s – including Grace Cossington Smith’s. Barbara Hanrahan’s apparently unrelated fiction picks up nicely on the masculine body.

But the cultural dominance of causality and paternity/filiation as plots and paradigms is not subverted by the feminists’ fictions, which are still in a filiative (substitute less masculinist term, if you will) relation to the perceived patriarchal painting.

Not only are these and all the other stories – save one, for this reader – wonderful, but their relation to the Smart and their interrelations with each other are also endlessly a source of speculation and wonder. What a pity – and we have no right to assume it is Daniel’s responsibility until we know who declined her invitation – that there is no Walwicz or Capiello or Loukakis or Castro or whoever. For then it could be said that not only is Expressway an exciting book, which it is, but that it represents not only the State of the Art but the State of the Nation in 1989.

Even so, it is to be hoped that not only will Penguin place it in the bookshop at the National Gallery of Victoria, but that it will promote it in the United States and the United Kingdom. It is an undeniable tribute to the sheer energy and variety of Australian writing now, as it is to Helen Daniel’s judgement and energy.

And just think, we may have here many gifts, many bonuses. That is, stories that would not have been written had not Helen Daniel sent out invitations to her symposium.

Postlude

‘Unreal, give back to us what once you gave:

The imagination that we have spurned and crave.’

Don Anderson will have a current bio by now

Comments powered by CComment