- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Short Stories

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Stephanie Johnson writes short stories and writes mainly about women. It’s as though there’s a specific genre in current writing that ties together these two kinds of writing, for women writing about other women in short prose pieces make up a distinct category that includes almost all of the familiar names of women writing in Australia now. These women writers include migrants who have made their homes in Australia and write from that position. Johnson, for instance, is a New Zealander.

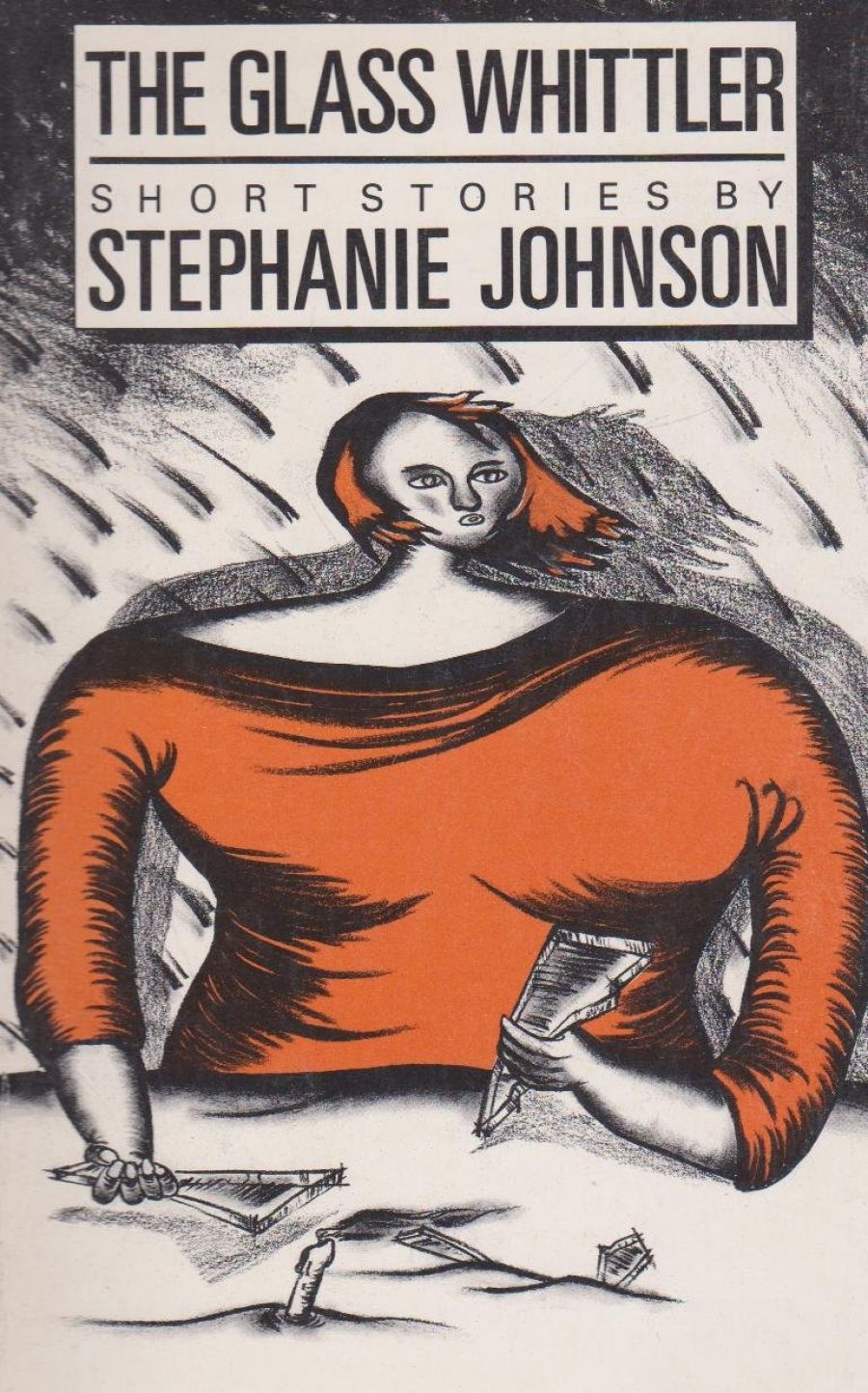

- Book 1 Title: The Glass Whittler

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 94 pp, $9.99 pb

Most of the women in these stories are set up – by circumstance, by themselves, but mostly by men. This is literally true in a story called ‘In a Language all Lips’, where an Arab terrorist sends his pregnant girlfriend back home to Ireland by air with a bomb in her baggage. The story shifts between her vision of romantic love, in italics, and his vision of brief and bloody fame, in ordinary type. There is nothing ordinary, however, about the obscene power he has over her: ‘People will look up between the buildings and see a knife flash in the sky, a red slash in the belly of God. That will be you. Later on dusty streets I will think of you and wonder if it is you between my toes.’ Against such power, romantic love is simply a vapour trail.

‘The Thinning of Nola’ is about a woman’s body lovingly made over into something grotesque. ‘It wasn’t as if she ever wanted to be this big … If she’d never met Helmut, she would never have got so large.’ Nola has put herself in Helmut’s hands and, while she sings along as Queen of the Night to The Magic Flute, she balloons out as an extravagant metaphor of man-made love. What saves this story from an easy programmatic shape – Nola loses weight and regains control of her life – is the ending. ‘He like his women small’, she says of her new romantic interest.

If Nola’s story tell us that fat is a feminist issue, then Robyn, the heroine of ‘The Invisible Hand,’ tells us that a woman’s voice. ‘ever soft, gentle and low,’ is a feminist tool as well. Robyn takes on the role of bread-winner by going into business in the sex industry to provide a very modest degree of comfort for herself and Macha, her daughter. The story focuses as much on the reaction of a couple of women friends as it does on the setting up of the business and it’s here that Robyn carves out a space for herself as a woman in control of her life. ‘Sue has Oliver by the hand ... all of the we-are-oppressed-women-together gone out of her voice completely.’ This is another voice of feminism. ‘Sue’s biggest worry is balancing her heterosexuality with her politics. I know this because she told me.’

Johnson is flexible enough to come at her subjects from more than one angle. ‘You’ll Sleep With No Other’ is a parable about sex and advertising that casts a male sex symbol as the protagonist. It’s not as successful as the other stories. Johnson doesn’t handle the form as confidently. The talking beefcake on the billboard has a flat, naïve voice that is perfectly consistent but trivial. The conversation of the two gays passing by – ‘“I bet his bum isn’t as red as mine is,” said the other man, uncomfortable in his tight pants.’ – is a cheap thrill.

The title story, though, is a real thrill. And the narrator describes a position for Johnson when she says:

Sometimes he shouted at her to go back to where she came from the tiny islands shaped like a question mark at the bottom of the world where people retained a kind of dignity, and mostly held their souls inside them at night. She considered returning, but she carried the obligation from the place of the question mark. The obligation was to see the rest of the world, or at least this ancient red continent, and report home.

Johnson’s report, though, is addressed to the women and men of the ancient red continent. These tales of romantic love and ideology and failure are cautionary tales. They are tales of the heart whose lessons are offered in lucid, calculating, and often heartless prose. The genre of stories by women about women is no longer a sentimental one.

Comments powered by CComment