- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

In male (I do not, just yet, say ‘patriarchal’) discourse, woman is man’s supplement. The feminist’s perennial dilemma, then, is how to intervene in that discourse which is forever reproducing the very hierarchy that suppresses and excludes her, when – by the power of its appropriation of common sense – that discourse operates not as though it were given her by men, but as though it were simply ‘given’.

- Book 1 Title: Christina Stead

- Book 1 Biblio: Prentice Hall, $24.95 pb, 155 pp.

Such is the problem that Susan Sheridan – feminist and lecturer in Women’s Studies at Flinders University – faced when she undertook the task of adding Christina Stead to Harvester & Wheatsheaf’s Key Women Writers series. Stead’s aversion to what she insisted was the self-serving bourgeois nature of the women’s movement is well known: ‘She spoke of the movement being led by “political types”,’ Sheridan reminds us, quoting from one of the many interviews Stead gave in the decade or so before her death in 1983, ‘who cared nothing for ordinary women, whom she characterised as “the poor little struggling housewife”.’

But if Stead’s life is resistant to feminist appropriation, surely her work must redound to the credit of those themes, characters, and concerns which are the stuff of women’s issues. A further problem for Sheridan is that this both is, and is not the case. ‘The placing of Stead’s characters in a tradition of “feminist protest”,’ she argues, is inappropriate, because:

With this model of feminist criticism, the feminism that is its object is sought in the text – or even in the writer herself – as a recognisable, angry or subversive protest against the oppression of women. Stead’s texts resist this approach and challenge its assumptions. To offer an alternative feminist reading, then, we need to locate feminism in the reading process, rather than in the text - to offer readings from feminist positions, rather than seeking to uncover a feminism already present in the text.

Whereupon Sheridan engages with the novels, raising matters of concern to the feminist as much, perhaps, as to any reader whose intellectual curiosity extends to a consideration of new and vital perspectives on Stead’s fiction.

This is especially so in the chapter on the ‘woman-centred political novels,’ I’m Dying Laughing and Cotters’ England, which Sheridan reads as inversions of ‘the conventional hierarchy of signification over the sheer force of language’. These inversions are brought about expressly by their ‘female “angle of seeing”,’ enabling gendered perspective which makes these narratives ‘iconoclastic in relation to the genre [of the political novel]’. That their iconoclasm has been overlooked till now – inscribed though it is in the unexpected rendering of the political through ‘the comic modes of farce, the grotesque, and so on’ – is a sign only that these modes have still to establish ‘a firm place in constructions of a “female tradition”’. This offers up to feminist literary studies a new project, one that Sheridan herself might be tempted to undertake in the future.

Of course, not all readers will be predisposed towards the necessity of such a project. Indeed, Sheridan will doubtless be accused of spoiling the ‘purity’ of Christina Stead’s fiction by infecting it with the feminists’ ‘partisan’ concerns, as if the unadulterated text were ever more than someone’s ideological fiction, and the sun revolves around the earth, which is flat, and …

Not that we should be uncritical of Sheridan on the grounds that she is a feminist. On the contrary, she herself repeatedly cautions the reader against complacency:

Part of feminist criticism’s inheritance from the humanist tradition is an explanatory model of reading: a hermeneutic tendency to seek out a text’s presumed hidden meanings, that will, ideally, cohere around a single unifying or even causal principle such as ‘the search for identity,’ or ‘the critique of the patriarchal family’. There are, inevitably, traces of this model in my own and others’ readings of Stead’s texts.

By thus signposting the self-awareness of her writing, in terms of its blindness as much as its interestedness, Sheridan collapses the distinction between ‘primary’ and ‘secondary’ work (between patriarchal origin and dependent scion), and gestures at the status of the work as text.

This gesture traces an uneasy relation to post-structuralism, the influence of which is both acknowledged and implicit in her writing.

Uneasy, because the feminist is not just concerned with describing women’s experiences in terms of how they are shaped by the play of language, and certainly not at the expense of the disappearance of the social realm in which gender politics are played out. On the other hand, Sheridan knows the power of appropriating signs:

To read Stead’s fictions (from feminist positions) is to read not for ‘images of women’ in the exemplary sense, nor for authentic testimonials of the female experience, but rather to highlight, in the texts of a writer centrally concerned with what she called ‘the psychological drama of the person’, the work of discursive constructions of femininity in fiction.

It is a measure of Sheridan’s intellectual honesty, as much as her acumen, that she continually remarks on the troublesome nature of Stead’s writing. Finding at times an absence of ‘the kind of moral affirmations that literary critics most frequently demand from fiction’, she also finds (in Letty Fox and Miss Herbert) women characters who deny ‘the kind of access to the female experience which has been most prized in feminist literary criticism’. At all times she is struck by the ‘multiplicity of competing truths’ at play in Stead’s writing – particularly in that sense in which her women characters ‘both contest and comply with cultural definitions of femininity’. She makes these claims by characterising Stead not as a feminist crusader at heart (a claim that might, on the surface, be flattering to the women’s movement), but rather as ‘the great ironist of women’s experience in the postwar world). This claim, it must be said, might well be read as a trace of that ‘hermeneutic tendency’, which inheres, even in the most recalcitrant attempts, to read against the humanist tradition.

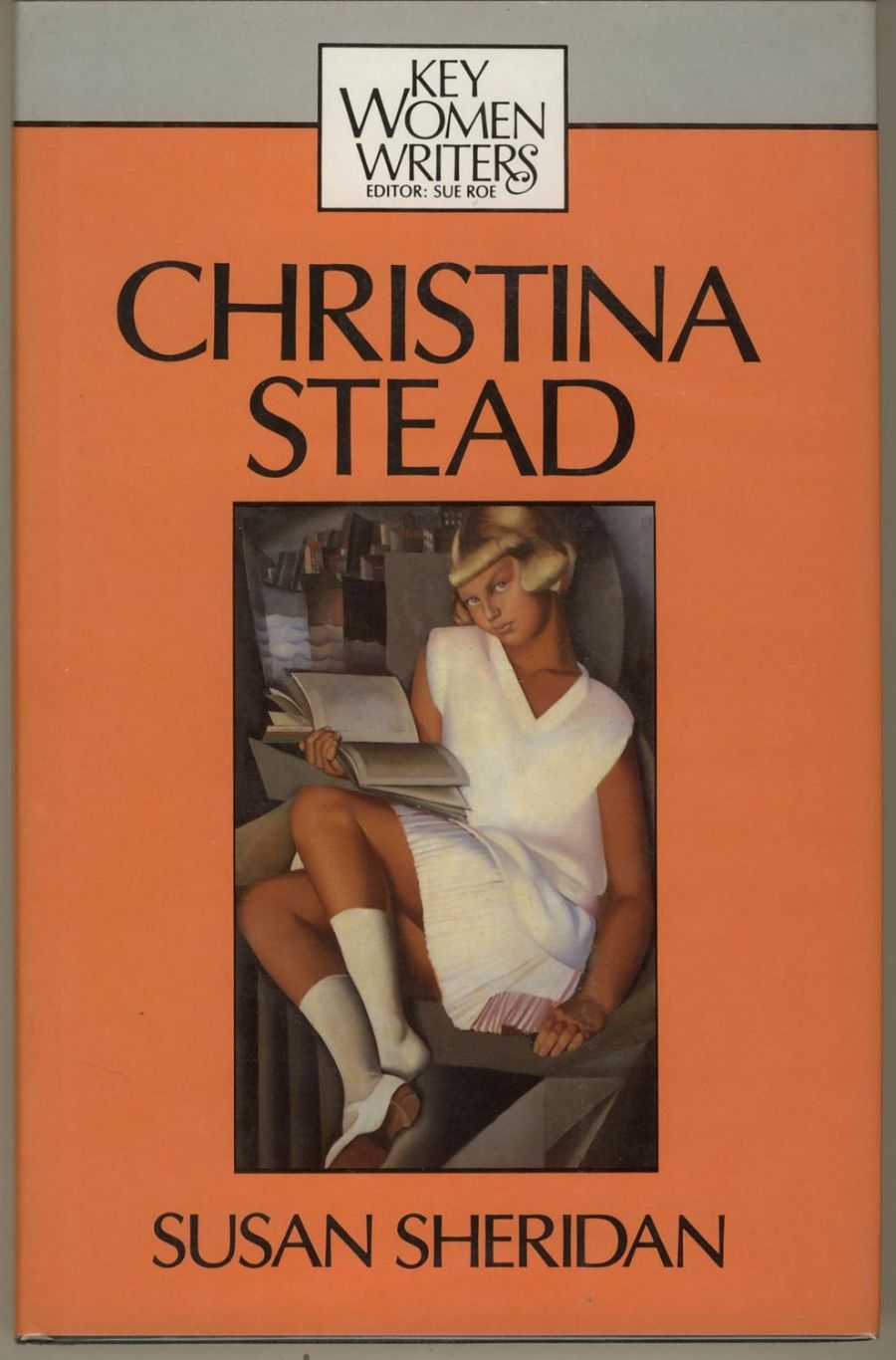

In the end, then, it is through her struggle to negotiate new positions in relation to Stead’s writing that Sheridan’s text is most suggestive. These positions (and surely we are invited to pun on the kinetic dimensions of this trope) offer an alternative to the erotic – even pornographic – position occupied by the woman (mere slip of a girl) on the cover of Christina Stead. The girl of the cover’s painting holds open a book with one hand, but her eyes return our gaze; staring out coyly at the viewer, she is distracted from her reading, however complicit she may be in this commodification of her femininity.

She may yet experience jouissance, but she will never read her book.

Comments powered by CComment