- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Commentary

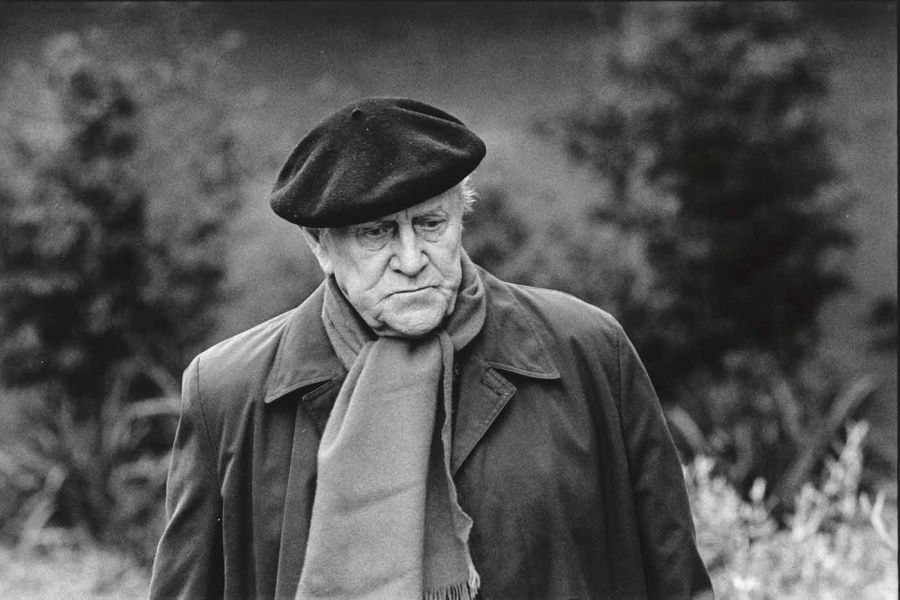

- Custom Article Title: Patrick White and literary criticism

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What we know and how we think and feel are socially and thus historically conditioned. But it can also be geographically conditioned. ‘Australia’, as Mrs Golson remarks in The Twyborn Affair, ‘may not be for everyone ... For some it is their fate, however.’ Our subject is Patrick White and criticism of his work in Australia and my argument is that ours is a culture in general, and a literary culture in particular, with an indifference to and perhaps fear of hermeneutics, which George Steiner glosses as some ‘essential answerability’ implicit in the act of reading over and above understanding or – Leavis preserve us! – evaluation.

That is not really as complicated as it sounds, especially when you apply it to White’s work. What he has to ‘say’, is not really a problem; the difficulty is essentially formal, in the way his work manifests a chaos within language itself and in any attempt at representation. For White ‘reality’ itself is the problem. As The Aunt’s Story puts it, ‘there is sometimes little to choose between the reality of illusion and the illusion of reality’. Although he may seem to be writing about the Australia we know, about landscapes and suburbs, and about people we might have met or at least seen or parties we might have read about, any reference to this extratextual reality is distracted and convoluted by a paradoxical struggle within the text itself, by a drive within the language and the determining force of the narrative, usually based on the logic of some underlying myth rather than the logic of human decisions and their consequences. Think, for instance, of the way that, in Riders in the Chariot, Himmelfarb’s crossing the Harbour Bridge by train becomes a crossing of the Red Sea.

I suspect therefore, to take a well-known example, that Hope’s famous attack on The Tree of Man came from something like this sense of betrayal, a feeling that, though the scenery, people, and life story were appropriate, it was not after all the ‘Mythical Bunyip’, the Great Australian Novel. What this novel, like all of White’s work, is about is rather ultimately some struggle within the self, what he called in Flaws in the Glass an attempt to introduce ‘to a disbelieving audience the cast of contradictory characters of which I am composed’, and, even more problematic, to write in tune with some ultimate scenario, some ‘grandeur too overwhelming to express’. This, in his view, is what writing is all about, ‘a deadly wrestling match with an opponent whose limbs never became material, a struggle from which the sweat and blood are scattered on the pages of anything the serious writer writes’.

That is why, for all their sprawling length, there is a sense of fragmentation and incompleteness about these texts – and they are texts in that their meaning is and must necessarily be incomplete, rather than books whose meaning can be completed and understood. But that is also why many Australian critics seem to have been, and still are, so uncomfortable with them. Kylie Tennant's 'when Patrick White gets mystical I creep out the door’ is perhaps the shortest and clearest statement of this discomfort. At the other end of the scale David Tacey’s Fiction and the Unconscious, so far as I know, is the longest. But his book, too, is based on a refusal to allow White to break the hermeneutical circle, to disestablish the sense of reality that defines the limits of what we can know and therefore what stories can be about. For Tacey, it is Jung’s work that tells him what can be believed and what is a valid interpretation of White’s work, so that any two readers can be assured of reading the same story. More simple-minded critics of the nationalist persuasion, of course, rejected it in similarly prescriptive fashion as being ‘un-Australian’.

But, to return to the Derrida quotation, these critics seek to ‘decipher’, they treat material which is highly symbolic as if it belonged to the domain of sign, the literal representation of the common sense of things, what White called ‘dun-coloured realism’. His works, however, reverse the metaphysical ground rules. Their emphasis falls not so much on representation as on the act of representing, on language, sometimes, as reviewers in the early days primly regretted, used ungrammatically and nearly always ostentatiously, upsetting the suspension of disbelief that makes possible the illusions of ‘fictional-realism’. The critic’s anxiety is therefore quite explicable. To challenge common sense in this way may in the long run threaten madness to those whose definition of reality is limited.

More recently, of course, this challenge has become the bread-and-butter of high theory, especially of the more esoteric devotees of critics such as Derrida who delight in the notion of literature as play – often, it seems, as a release from social responsibility. But this is not a way I want to take. Nor is it, I think, one White would have approved. Authorial intention is still worth attention, even if it is sometimes betrayed or revised in the work. In White’s case, however, it is not. It is precisely because of their ‘ludic’ nature that his works are socially relevant and have things to say of profound importance for Australian culture. Aesthetically self-conscious, his works engage non-referentially the attention of the whole person upon ‘a configuration of happening existence’ (Don Via).

His emphasis on the inevitability of suffering and our subjection to physical necessity and his preoccupation with death or the dissolution into madness with which so many of his works end rejects the notion of civilised life as a decent compromise, a coming-to-terms with harsh reality, in favour of some further possibility. ‘Self’ here ceases to be a solid, self-enclosed, and self-defining entity, challenging sexual taboos to become a dynamic interplay of contradictory forces, a goal rather than a given, a goal, moreover to be sought after painfully and often fearfully though also strangely joyously as, for instance, the joyous absurdities of The Twyborn Affair, or of Memoirs of Many in One. As Foucault puts it in Madness and Civilisation, however, such moments in which the work of art verges on madness may represent ‘the beginning of the time when the world finds itself arraigned by that work of art and responsible before it for what it is’. Moreover, this arraignment is not merely theoretical. Because the attention it demands is non-referential but experiential, it calls for some kind of decision, if not a change of life at least a change of perception.

This is what White was quite consciously seeking, at least from the time he wrote ‘The Prodigal Son’, declaring his intention to contest ‘The Great Australian Emptiness’. True, this began in Happy Valley, however immature that work might be. And so, too, in The Living and the Dead, Eden declares her belief in the necessity of a change that is not just political or social but a ‘change from wrong to right which is nothing to do with category’, and to ‘unite those who have the capacity for living ... [and] to oppose them to the destroyers’. It is in this challenge, however, that ‘difference’ enters the ‘region of historicity’ and thus, I suggest, joins forces with the critique of Australian culture and society which is an enduring strain in Australian criticism.

True, as Eden’s speech makes clear, White turns that strain to his own ends. What he is concerned with is not just politics or society but the basis on which they rest – that is, with matters ontological and epistemological. As he said, he is not concerned with realism, dun-coloured or otherwise, he does not want to reduplicate the world, believing, like Vita Sackville-West, that ‘one of the damn things is enough’. Rather his works are ‘poetic’, their referent available only through the world of the text. They refer by redescribing, indeed by reinventing, ‘reality’, seeking a new kind of understanding from that in which ‘dreams and facts [are] locked in an architecture [that does] not appear alterable’. (The Vivisector)

This is a characteristic Modernist project, of course. But a text such as Riders in the Chariot shows how subversive it can be in the Australian context. In Voss, Turner, for example, sees this concern with the visionary, as a concern with ‘mad things’ that threatens ‘to blow the world up; anyhow the world that you and me knows’. In the first place this subversion is thematic. White’s protagonists are outsiders and failures, people usually disregarded for this reason. But his preoccupation with them and their sufferings at the hand of a society that is presented not only as stupidly complacent but also as vicious also challenges this society’s premises and the moral confusion on which it is based – that money and success represent virtue and their opposite, evil, a confusion, as Paul Ricoeur remarks in The Symbolism of Evil, of the cosmobiological with the ethical since it is unable to distinguish faring ill from doing ill.

This insight is not merely theoretical, however. It is also compositional. A Fringe of Leaves, for instance, takes us to the heart of the whole complex of fear and guilt – defined as ‘feeling responsible for not being responsible’ (Ricoeur) – that underlies our attitude to Aboriginal people and culture. Here and in other works in which Aborigines and/or blackness figure, he challenges the basis of our racism, what Abdul JanMohamed calls the ‘Manichean allegory’ of colonialism in which white is to black as good to evil, superior to inferior, civilised to savage in the name of another kind of authority. This, to return to an earlier point, is the authority of language, of language as revelation, a ‘rhetoric of overturning’ (Ricoeur) which persuades us that a transfigured, or at least different, existence is possible.

In effect, then, White sees himself as living in language as others see themselves living in society, and this is what makes his work so difficult, since this attempt to salvage language from all its unconscious as well as its social restraints, appropriating it totally, undermines any attempt to come to terms with, much less ‘explain’ it. But it also saves him from the fate of Narcissus, since he can only find himself by means of language, something which is given rather than his own creation. This mirror in which he recognises himself, ‘all blotches and dimples and ripples’ as it may be, is nevertheless other than himself and thus able to mediate his entrance into the symbolic order by means of its authority.

Self-exploration may be the beginning of his work, but in this way the self then becomes a resource for this discovery of and submission to authority. And so Narcissus becomes prophetic. Meshing with the figure of the explorer whose exploration is into spiritual and psychic rather than merely physical dangers, self stands in judgement over the culture of complacent containment, epitomised by Mr Bonner with his longing to be ‘safe in life, safe in death’. The authority it defers to is that of the Other, of some ultimate reality that stands against self and society, interrogating certainties and values and calling it to ‘go further’. Voss is the closest example here but all of his novels are variations on this theme.

It is here, of course, that Kylie Tennant and her like begin to ‘creep out the door’. But it is important to remember that what is invoked here is not the conventional ‘God’, the ‘Divine Ventriloquist’, projection of social and emotional need, but rather a ‘Divine Vivisector’, whose work is to overthrow and overturn, and whose manifestation is like the sting of the wasp, exciting rather than soothing. As Mrs Volkhov’s account in The Vivisector suggests: ‘I got stung not by putting up my hand.’

Comments powered by CComment