- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This collection is an eclectic one. John A. Scott includes translations from Apollinaire, Ovid, John Clare (a translation from prose) and a little-known contemporary French poet by the name of Emmanuel Hocquard, together with a selection of his own work. This at first dauntingly disparate group appears to be united by the myth of Apollo’s son Orpheus in which creativity and the absence of the beloved are inextricably entwined (‘I come here for Eurydice, whose absence / filled my life – and more – could not contain’). Another aspect of this myth important to Scott is represented by Rimbaud’s A Season In Hell, in which spiritual suffering and occult experience are vital elements of artistic creation.

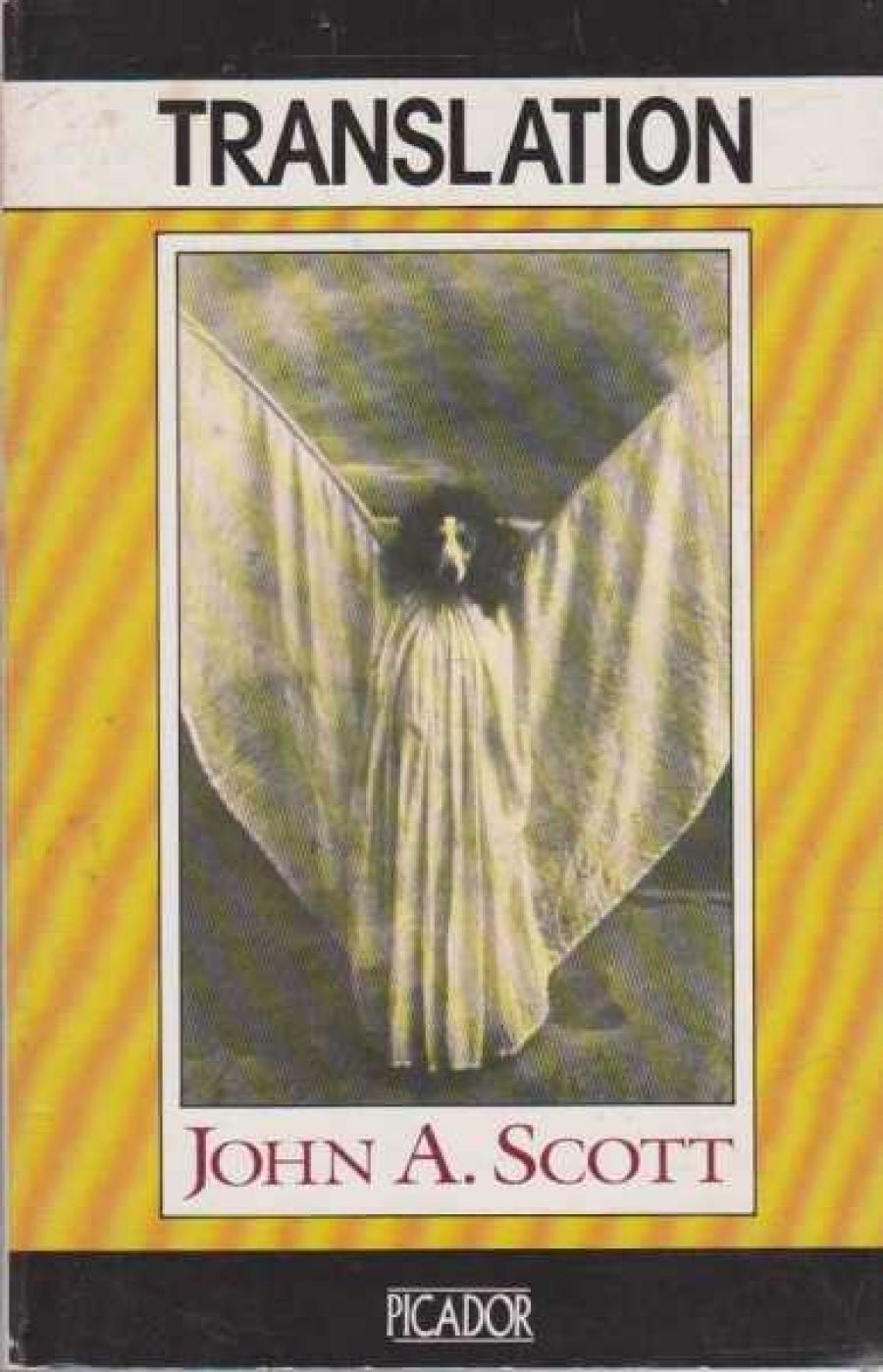

- Book 1 Title: Translation

- Book 1 Biblio: Picador, $15.99 pb, 223 pp

From love as affliction, Scott embraces the madness of the solitary with its promise of poetic vision. There are moments in Translation recalling Rimbaud’s project of sensory derangement (‘I became an adept of simple hallucination: in place of a factory I really saw a mosque …’) and the disconcerting switch from ‘I’ to ‘you’ in Apollinaire is symptomatic of the loss of identity associated with the experiences of both intense love and madness. This is recreated in the poems dealing with John Clare, ‘The Northamptonshire peasant poet’ who spent close to half his life in an asylum. After a failed love-affair, Clare turns to poetry and, as Scott perceptively points out, this poetry re-enacts the Orphic myth in its celebration of loss. In this way, the creation of poetry becomes a substitute for the absent object of desire:

& So He Had Stepped Out Awhile

& Shut Behind The Bastille Gate

In Search Of Mary Once His Bride

Whose Absence Filled His Life Of Late

The orthographic eccentricities suggest the psychological turmoil of the subject. In Clare’s case, the disturbance is so severe that personality and language threaten to fall apart. Paradoxically, in translating from his own experiences, Scott scrupulously protects the unity of language. As an extremely accomplished technician of rhetoric, he writes of obsession with a careful blend of linguistic resourcefulness and voyeuristic display. The pornographic streak in Scott (a feature of the prize-winning St Clair) is one of the most difficult aspects of his work to come to terms with but one consistent with a preference for the passion of the word. In this sense, writing takes on a fetishistic function. Sexuality is described in Scott’s work with a sense of repulsion and a morbid concern for details, rather than as rapture or celebration. Indeed, very early on in the collection Scott makes explicit the notion that poetry comes into being primarily through this absence of sexual expression (‘How the poem fills with blood and will not rest unless it be with her, even now’) although it proclaims its aspiration to a consummation that is repeatedly deferred.

It is perhaps this quality of repression that generates the elegiac mood of much of Translation. In the title sequence of the first section, titled ‘Elegy’, Scott exploits the strongly cinematographic bent of his imagination in a distinctive kind of poeticised prose. The result is a disconcerting mixture of Gothic and surreal elements which reminded me of the film Providence. The tone of the writing is carefully controlled and persistently teases with its references to assumed knowledge and recondite allusions (‘And you still wish – and after all that has occurred – to seek her through the child? And even there? You wish to journey to the other place?’). The text deals with the last film made by a director called Camini and involves the birth of a bizarre jackal-headed animal-child. The narrative unfolds through a series of highly mannered conversations interspersed with descriptive details and reflections by the central character, Aldo. It finishes with a bizarre evocation of the dead Rimbaud being embalmed. Isabella, the poet’s sister, speaks of the ‘poison’ that is Rimbaud’s legacy:

It is the signature of the illiterate. It is perverse. It is illicit. It is the heart of the unknown, obliterating everything in its profusion.

The highlight of the collection is provided, undoubtedly, by the translations of ‘The Elegies’ by Emmanuel Hocquard. Apart from a volume of poems entitled A Day In The Strait, little of this poet’s work appears to have been translated into English. The style of ‘The Elegies’ is intensely personal, hermetic and mythological, qualities clearly apealing to Scott. The theme of time is central to the series, with Hocquard exploring the notion of timelessness within the fluctuations of history:

And yet there. There you must recognise

that time will have worn away noth

ing.

Everything is, on the contrary, still ter

ribly

intact.

Who would come to speak of remember

ing?

Since it is here, not elsewhere;

Now and like this,

Neither before nor ever otherwise.

Like much of Scott’s own poetry, Hocquard creates a bricolage of language that leaves the reader to piece together possible connection, associations, ideas. Despite this general tendency, one also finds snippets of story and a strong historical flavour.

Translation is an extremely challenging work and represents the most comprehensive embodiment of Scott’s idiosyncratic creative project. Whatever reservations one might have about the nature of his quest, it is impossible to deny the energy and linguistic ability he manages to capture on the page.

Comments powered by CComment