- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

You can’t write a review of millenarian ‘time-pieces’ without showing your hand. I hereby declare that the first thing I do on looking into such a collection is a simple calculation, to which the answer in this case is 16:25.

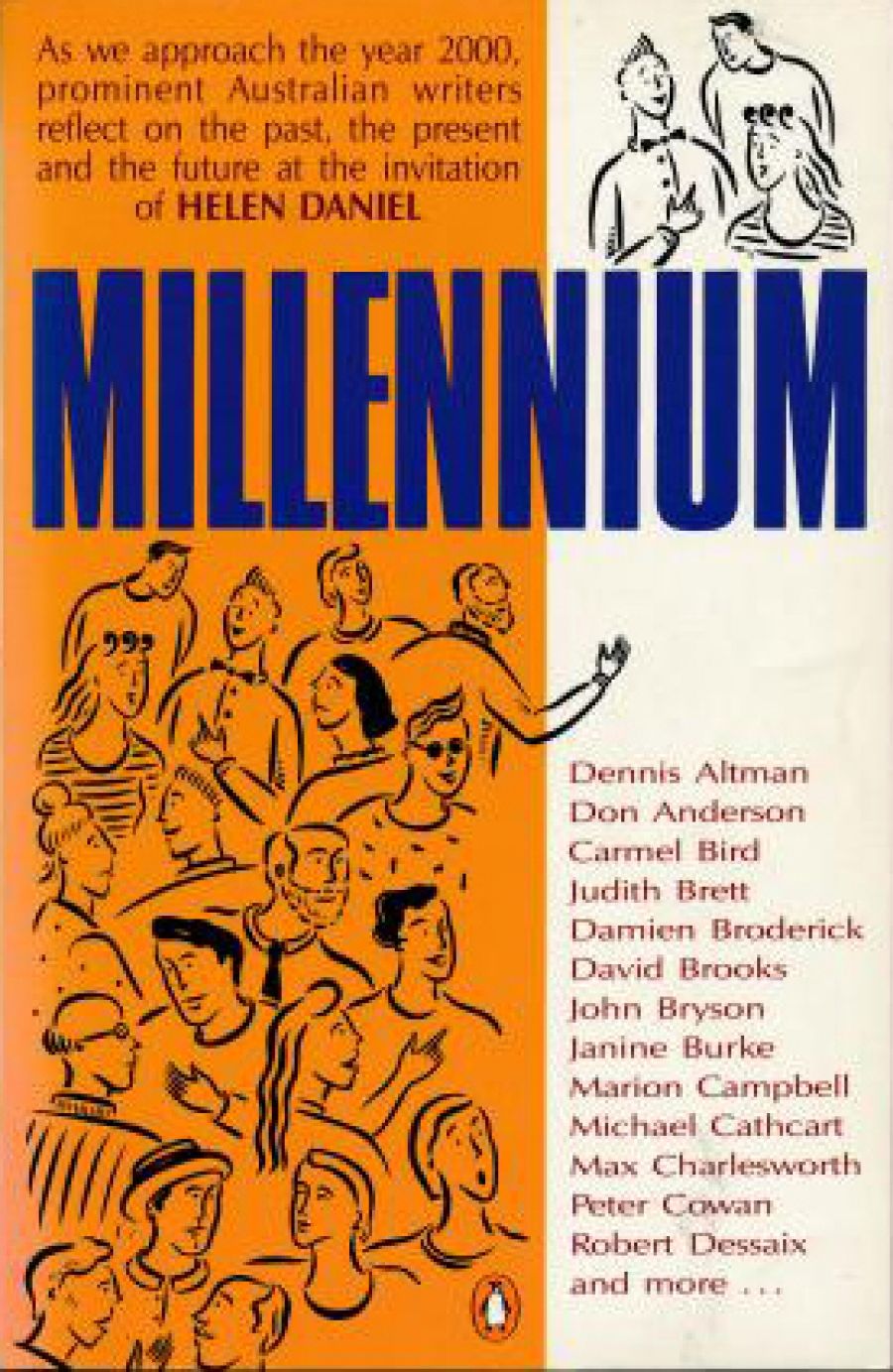

- Book 1 Title: Millennium

- Book 1 Subtitle: Time-pieces by Australian writers

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $14.95 pb, 342 pp

I’m not quarrelling with the selection of women who do appear in Millennium. As to other choices, more later. Meanwhile, it seems as good a place as any to begin the difficult task of commenting on forty such various pieces by looking at the ways women’s responses to the challenge to ponder the approach of the year 2000 might be characteristic, and in what ways different from the men’s contributions.

In a review of Karen Lamb’s 1990 Penguin collection, Uneasy Truces: Stories from the love zone, I remarked that it’s not easy to find male writers who will write about ‘relationships’ in any manner that exposes a stance – reveals their parti pris. Thus you find the same story by a given writer being anthologised over and over because it’s the only one with any such qualities.

And so it’s good, for a start, that the pieces here are not only stories but take all sorts of forms, and some of the male contributors choose to simply forecast in socio-political terms what will happen or must happen. Dennis Altman’s ‘Scenario’ takes in the ever-broadening diversity of the Australian society and our likely continuing insignificance in global terms. He argues for recognition of the insights of environmentalism and feminism: a genuine balance between ‘communal provision of services and respect for individual diversity’.

Ah, yes, Dale Spender replies, but meanwhile we’re drowning in a sea of Information Technology without a canoe, let alone a paddle. And let us beware new Ageism, chimes in Finola Moorhead, with its reliance on the old conquistadorial myths; Kill to Survive in the ever-redefined struggle between Good and Evil. Remember that women of every generation have to reinvent the wheel, says Moorhead. I certainly remember the mish-mash of 1970s Back to Nature New Ageism, combining attenuated animism with skin-deep green-ness and liberationism which somehow involved a new generation of well-educated young women in labourintensive macrobiotic kitchens. It took a lot of them a long time to untie the homespun shackles, and the Greens have yet to establish their bona fides in that department.

Kerryn Goldsworthy comes at the question of what the Real Story is in a meditation on the magical harmonising powers of physical contact: the genesis of any plot from Biblical onwards, the ‘incarnation of intention’.

A voice such as Max Charlesworth’s, on the other hand, seems to me to be a voice in the wilderness, reverting to the Grand Narrative of God’s plan. He invokes the ‘divine’ (and human stabs at it) with never a query as to the effect all the forms of transcendentalism have had on huge populations down the centuries (surely the bane of the planet). He takes for granted those hierarchical schemes in whose terms the material world is always the Lower Depths and whose logic authorises religious and social orders created in the image of Man.

(‘The white male god was winning. Not a result I fancied’, says Moorhead.)

Helen Daniel’s letter of invitation to contributors asked them to respond in ‘any mode, from portentous to ludic’. This elicited the sometimes twee larrikin in some of the boys, such as Jack Hibberd, Barry Oakley, and Dinny O’Hearn. O’Hearn’s character is the mickey-taking, reactionary sceptic cast in the role of Antichrist in a staged Apocalypse organised by a very cagey and charismatic Aboriginal ‘Saviour’ and his manager. Oakley’s is an octogenarian ‘Fosterball’ faithful and Hibberd’s a resurrected James Joyce down under, where the survivors are ‘Americans, AustraloAmericans and Japanese’.

For others, millennial whisperings came to them from the past. Futuristic fiction has notoriously cast the time to come in the form of the past, often projecting fantasies of brutish origins onto an imagined future stripped bare by holocaust and taking new-old brutish shape. Here, some of the writers make monkish tales rather than monkey-tales (Robert Dessaix and Andrew Riemer) and David Brooks offers a tale-out-of-time whose characters have Romaniansounding names and in which, in poverty and cold and in a barn, a Virgin Birth takes place. This one works rather well, but I think Dark Ages clerics are best avoided after the death-defying efforts of David Foster in Christian Rosy Cross. (Why isn’t David Foster in this book?)

Humphrey McQueen locates the need for new languages with which to speak the future – not just new vocabularies of the mechanical or flippant kind invented by Hoban/Burgess or Samuel Butler, say, but one emerging out of and reflecting new social conditions. On that point, it seems to me a pity not to have included contributions by cultural critics/theorists who might have done some useful contextualising of the other pieces by placing them where they fit among the discourses of the late twentieth century (Meaghan Morris, Liz Grosz?).

There are good stories, too, notably Rod Jones’s and Janette Turner Hospital’s, which is perhaps my favourite in the collection. ‘The Endof-the-Line-End-of-the-World Disco’, set in a bar in remote Queensland around which the waters are slowly rising, and away from which calmly sails Gladys, free at last, ‘higher than the clothesline, euphoria bears her upward … Any second now, the broken legs on the back lawn will come rushing to meet her, but she doesn’t care … a child on the last big dipper’.

I can’t indicate all the approaches, all the styles; I’ve talked mainly about ideas. There are exhilarating pieces, lots of them, from the formal angle, containing more submerged ideas: Mary Fallon, Nigel Krauth, Tom Flood. Flood’s story is powerful, though there is a danger in recounting a precise violence in emblematic and archetypal terms in that it seems to authorise violence as awful but preordained.

Daniel has written an evocative, resonant introduction and uses selected phrases as leitmotifs at the bottom of all the pages in each section, the sections themselves being labelled with such phrases (for example, ‘Backwards is forwards, pontificated the ruddy giant’). While I’ve complained about omissions (I’d have liked some journalists in there; Adele Horin or Marian Wilkinson?), there are evident attempts to include essential perspectives. Nick Jose suggests the Wisdom of the East – a little sentimentalised. Archie Weller’s is rather a lone Aboriginal voice, although Whites, encouragingly, include that perspective with humble determination, as in John Hepworth’s endearingly optimistic ‘Remember the Future’. John Bryson’s representation of the Dyak chief and the cycle of selection, harvest, redemption (that is, sacrifice), worried me. I like Michael Cathcart and Victor Kelleher a lot. Marion Campbell is darkly suggestive and Robyn Williams amusing but worrying in the amount of mileage he takes out of a few unflattering Iron Curtain travellers’ tales. Don Anderson reflects on the apocalyptic titles of volumes of literary criticism in a worldweary kind of way.

You should read this book. Buy now and save to give as Christmas presents in 1999.

Comments powered by CComment