- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The usher of the book’s title is T. Nelson Downs, long-time resident of Burleigh Heads. (The T. Doesn’t stand for anything; it was a parental whim.) He’s one of those wonderful, original, exasperating people full of impossible ideas (such as marketing gigantic ice sculptures for public occasions using skilled tradesmen brought out especially from Florence).

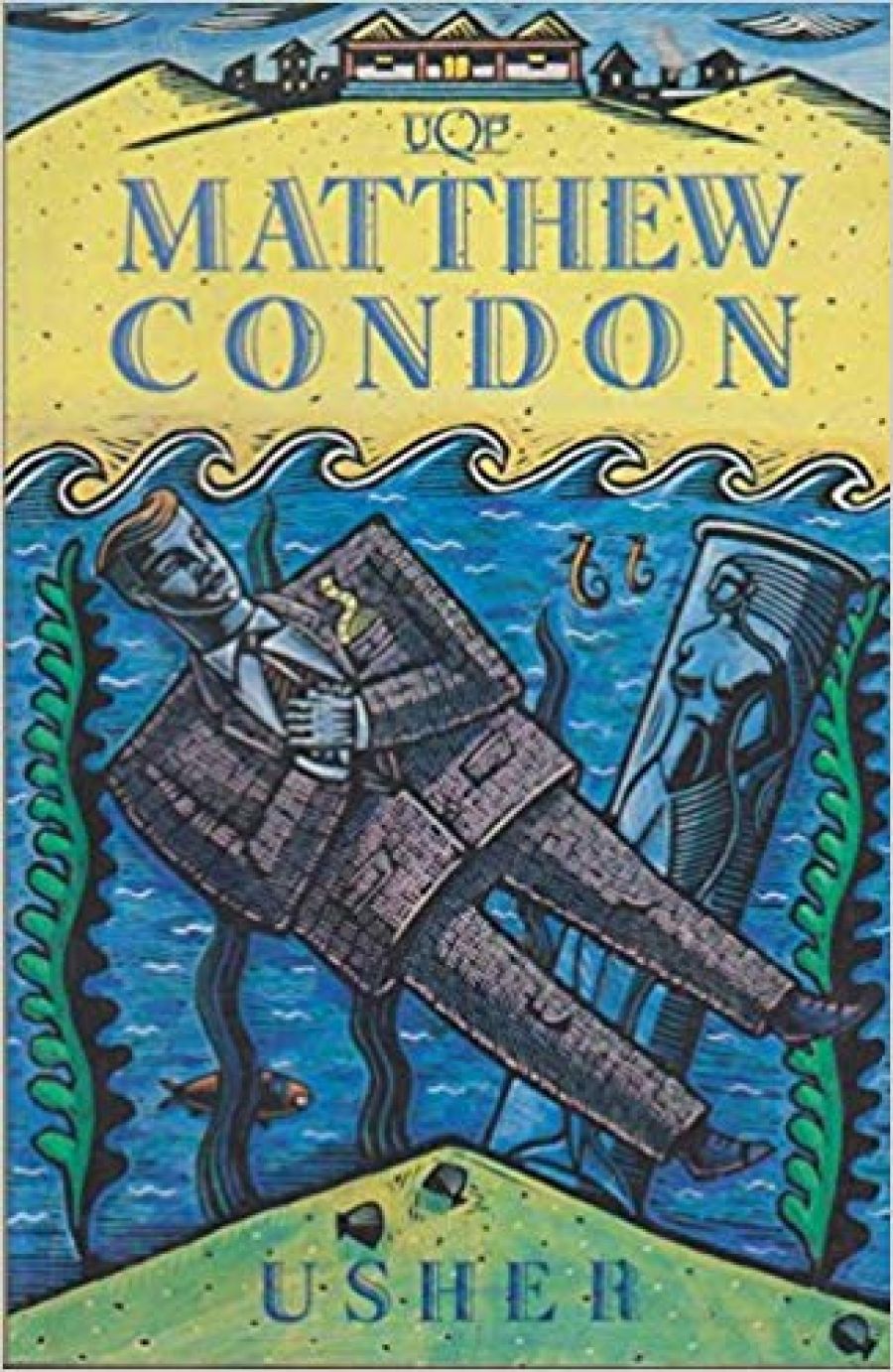

- Book 1 Title: Usher

- Book 1 Biblio: University of Queensland Press, 260 pp, $19.95 pb

As the novel opens, we learn T. Nelson has disappeared into the ocean off Burleigh Heads while screening Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. T. Nelson’s son Samuel, fleeing from grief on a journey of discovery that will take him around the world, protests ‘my father couldn’t be dead because I didn’t really know him yet’. Usher becomes T. Nelson’s obituary, something, Samuel the son believes, every person deserves because otherwise, without their story, all that is left is mere ‘meaningless junk’.

In this ambitious new work, Matthew Condon further develops themes evident in his earlier much-acclaimed The Motorcycle Cafe. In Usher, a son must come to terms with a father’s life in order not only to give himself a sense of place but to validate his father’s existence. In so doing, Condon creates a fable for our times.

A sense of family reaching across the generations pervades this novel. Urban Downs, T. Nelson’s father, has been a sucker to salesmen in his day, and T. Nelson himself succumbs to sweet-talking from ambitious politicians. In a section that it at once sensitive, comic and satirical, Condon presents beautifully T. Nelson’s gradual immersion into enormous folly. At the suggestion of a Burleigh Heads councillor who’s running for mayor, he gets in ahead of the plant poachers and ‘culls’ endangered plants for a government scheme. A politician doesn’t need a high profile, the wily councillor tells him. ‘The public don’t have to see him, not at all, but if they see green they know he’s doing his job.’

T. Nelson, the scapegoat, disappears. But is he dead? He is, after all, the usher of the Universe, where ‘the magic power of light and picture and screen was the creation of God’.

If T. Nelson is God, or a prophet, then he is a limited one. ‘You start digging and you might find something’, his son warns him. ‘Dreaming of the moment of discovery that would place the entire history of his nation in perspective’, T. Nelson does dig (literally) – another of his grand ideas – but misses the significance of what he finds. It is left to Samuel to become the keeper of the truth, the undertaker to corruption, the one who must go on shouting out the true story if T. Nelson’s achievement is to be more than that of a tragic clown. And after Samuel, his daughter …

As Samuel’s horizons widen during his around-the-world odyssey, his understanding of the past deepens. The style of this interesting and challenging book is apt. It consists of a series of non-sequential sections juxtaposing T. Nelson’s adulthood, his childhood, his father Urban’s youth, his son’s present journey and even the future (though by the time the book is a few years old it will have caught up). I found Samuel’s peregrinations across the United States less engaging than other parts of the novel; at times the pace flags. The author’s intention is clear – to present a series of vignettes, picture postcards, of a tawdry, sham world in which nature is never itself but everything is a representation – but sometimes these ‘strange fables of our private stories’ fail to bear the weight of the meaning Condon attaches to them; epiphanies that don’t quite incandesce.

Condon does achieve a fine sense of the past, the present and the future, particularly in the T. Nelson sections, and this extends the novel’s meaning beyond the Downs family and beyond Burleigh Heads. He also makes pleasing use of the four elements as metaphor. The sea becomes a resonant symbol. Around a great-grandfather Downs there has grown up a legend of a noble death at sea: the truth turns out to be much more banal. Through his son’s efforts, the life of T. Nelson Downs accrues more significance than that of his ancestor. T. Nelson becomes a sort of Everyman who lives on despite his watery disappearance. And, in a wonderful surreal section, Samuel by choice almost repeats his father’s fate but is rescued in order to make sense of it all.

Usher is overall a humorous book, warm-hearted, satirical, and in the end I think a sad one; a crier’s bell for our times. Condon presents a wicked picture of Joh’s Queensland that won’t necessarily disappear with the exit of any particular politician. Samuel, travelling across the United States by Greyhound bus, visits a tarted-up Indian reservation where he comes across another set of caged creatures – performing birds and animals including the ‘Gambling Galar’. And what, after all, has T. Nelson been to a large degree but a performer who gets dumped when no longer useful? If, as the blurb says, Usher presents a vision of a future purged of a corrupt past, it’s a fragile vision and Samuel, polishing the sham animals in an amusement park, will have to shout loudly to make himself heard.

Matthew Condon is an exciting new writer. Since the Universe, T. Nelson’s world-reflecting cinema, is so integral to the book, I’ll give Usher a David Stratton star-rating: ★★★★.

Comments powered by CComment