- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Tolerance and passion might seem, at first thought, to be peculiar bedfellows. Charmian Clift, in this series of essays first published in the Sydney Morning Herald and the Herald, Melbourne, combines the two in a dazzling and compellingly readable collection.

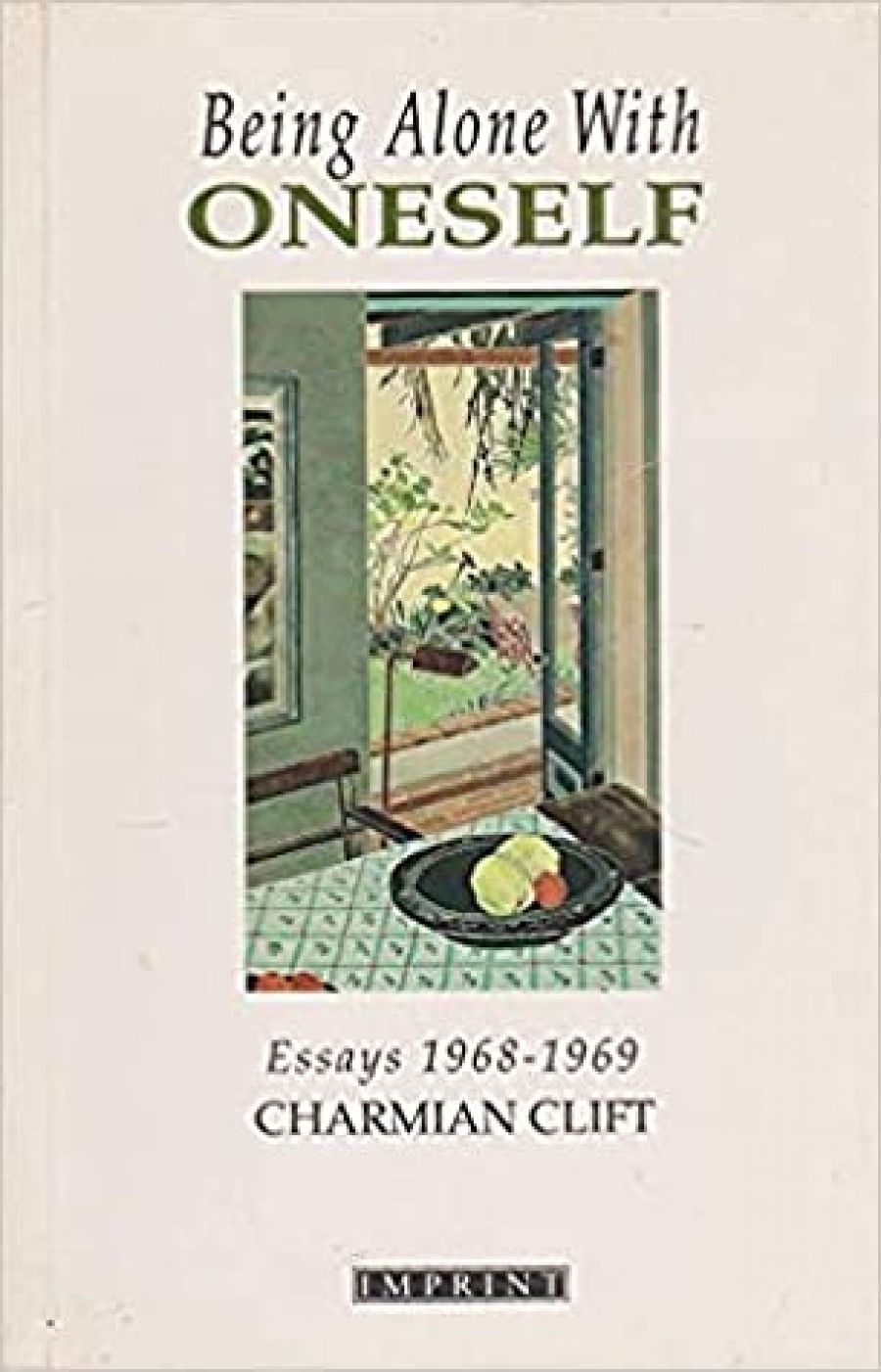

- Book 1 Title: Being Alone with Oneself

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus & Robertson. 333 pp, $16.95 pb

These essays, Clift’s last writings, were originally published in 1968 and 1969. Although an avid reader of her work, I had not read any of these essays before, being Elsewhere at the time. Mainly published in the women’s pages of the newspapers, I found them all the more astonishing when seen in the context of their layout, facsimiles of which are reproduced in the book.

While British newspapers allowed the Jean Rookes of this world an expansive (and usually unbroken) spread, Clift was surrounded by advertisements for wrinkle cream, Grace Bros and Walton’s stores extolling the advantages of a new refrigerator or washing powder.

A stirring cry for democracy in Greece was accompanied by an ad for a colic remedy, and the title essay, ‘On being alone with oneself’, played second fiddle to a Grace Bros ad for Watersun bathers – or cozzies.

That her writing (and readership) survived these indignities speaks for itself. As is evidenced by letters received by her, male readers also followed the jigsaw of her essays into the women’s pages.

Whether tackling the injustices of the means test in relation to widows, abortion, the manipulation of human genes, the temperament of her cat, charity balls, her children’s unwashed clothes, or even the letters written to her in response to her essays, the writing appears effortless, dashed off in a spare five minutes without needing any reworking.

But, as Nadia Wheatley points out in her thoughtful introduction, Clift was a painstakingly slow writer, whose method did not fit comfortably with the way she had each week ‘to think up a topic, and then often research it, plan the structure, draft it and draft it and draft it again’ before the Sydney Morning Herald car came on Saturday afternoons to collect the copy.

Often in ill health and low spirits, she had no respite from the demands required to eke out a living with a husband in hospital and teenage children requiring new school uniforms and food and shelter. Sometimes she touched on these aspects, but never in a self-pitying way. Her existence and well-being were precarious, but still the tolerance and passion remained in full strength.

In ‘Death by misadventure’ she writes about abortion:

It is a criminal act. But who is the criminal? The woman who seeks deliverance from the callous demands of nature, the doctor who helps her from compassion or uses her dilemma for gain, or the law which makes a relatively simple operation clandestine and therefore open to abuse?

Strong stuff, next to the ads for wrinkle cream and corsets.

Her championing of the student demonstrations in Sydney and Melbourne (this was 1968–69, remember) led to her being deluged with pamphlets, paperbacks, periodicals, and student publications. She thought their aims and ideals eminently sensible, but cautioned that destruction of the system was not defensible unless a new system could be instituted.

Similarly, while she made a stand against the Greek colonels (a situation she admitted feeling diffident writing about since she did not entirely understand it), she went on to write passionately of her experience of living for ten years in Greece and to caution decent middle-class Greeks not to become complacent in a way that allowed the Nazis to take over Germany.

Arrogance and bitterness were obviously not in her arsenal when it came to putting words on to paper – instead, passion and tolerance untainted by any of her professional or personal experiences shone through. Her sanity, compassion, and honesty reached out into the lives of suburban readers, bringing a new perspective to yesterday’s headlines.

Comments powered by CComment