- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

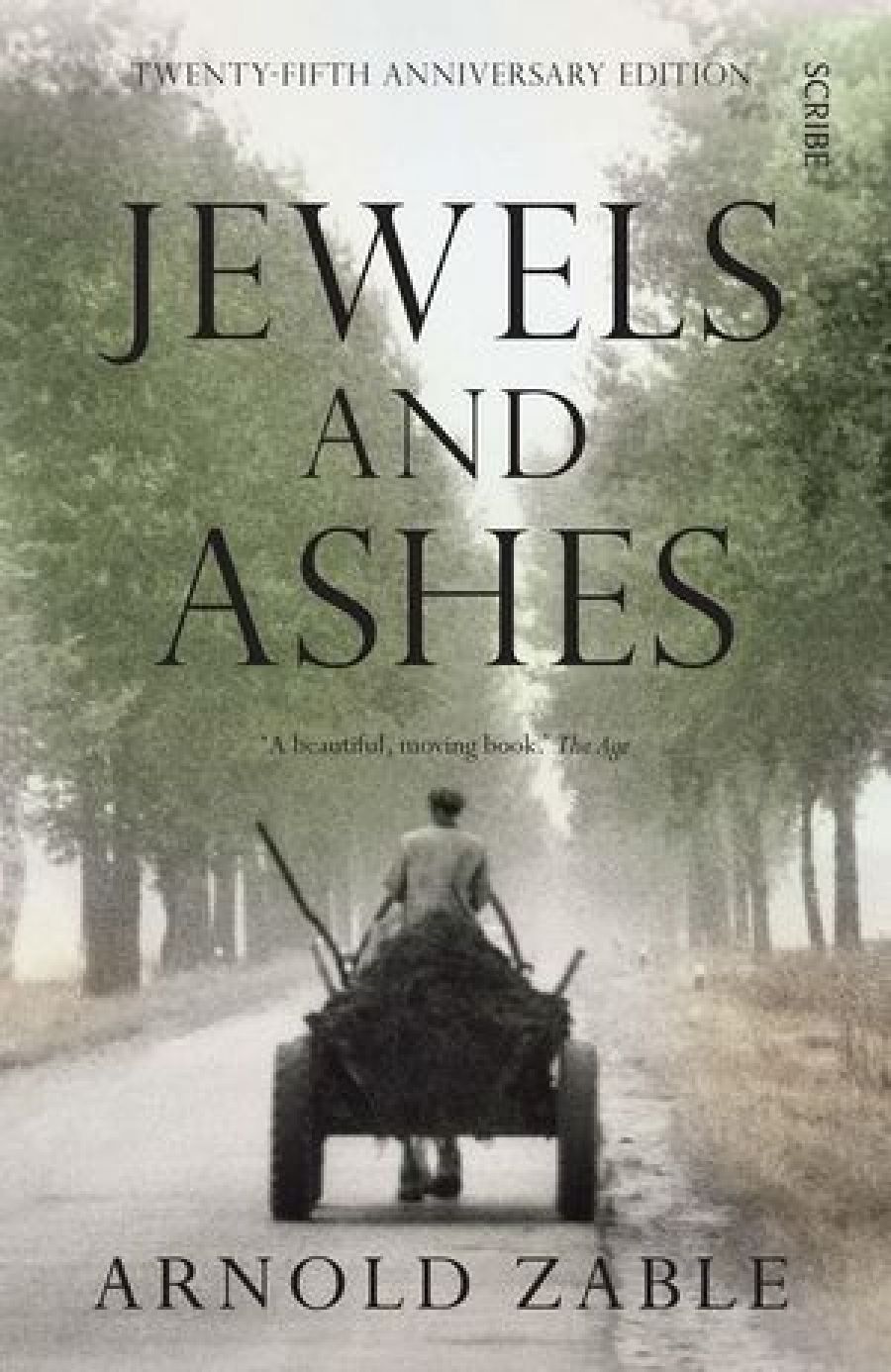

In the opening pages of Jewels and Ashes a man of eighty stands on a chair, his arms outstretched, describing the tree he remembers from his childhood. How beautiful and tall and wide it was, as it stood in the forest called Zwierziniec, on the outskirts of Bialystok, Poland. How strong his family was, how it branched and grew and prospered, in those years before 1939!

- Book 1 Title: Jewels and Ashes

- Book 1 Biblio: Scribe, 210 pp, $14.99 pb

Not that he hadn’t had years of stories, songs, books, discussions, and explanations of who was who, and what was what, and how the remnants of his family had come to sit in Curtin Square, Carlton, under the Moreton Bay figs, for Arnold’s father, Meier, is a good talker, and a philosopher. Listen to him:

The whole of existence is contained in words ... words are the source. This grass must eventually fade, whereas words eternalise our experiences and express the sum total of what we have been in our lives.

But there is that which can’t be captured in words – the silences of his mother, the sighs. Sometimes they can only be fathomed by a journey. Zable the younger describes his travels to the old country, to which he had been bound through time and space by a cord of imagination. Bialystok was the central destination, where the thriving Jewish community had worked and learned and prayed, where his grandfather Bishke Zabludowski sold the Jewish paper, Unzer Lebn, on street comers for forty years, where there was even a thriving Jewish underworld.

Zable starts in Beijing to catch the Beijing-Moscow express, in a trip that takes him west to Poland – a straight line on the surface but really a circling, hovering approach to the history of his family, his culture and his times.

Just put one foot in front of the other, and don’t stop moving until you have extracted your full measure of life from the day.

What can we hope to find in a place that we have never seen, in a town that holds only remnants of the community from which we sprang? Will we find people who look like us, think like us? Will they hold their arms open, and recognise us, take us in?

Beware of sentimentality. That is why I have lived so long.

Zable’s journey is taken with his father’s good advice. He has avoided sentimentality (a trap many of his contemporaries have fallen into when dealing with such matters) and travelled with clarity and insight to wander the roads and highways of his history, to meet the last, mad, delirious, driven Jews who stayed. Some did so to be with the brave Poles who saved their lives, and who they later married. Others stayed to tend the graves of the fallen, another, this elderly man on a tractor in the middle of the night, stayed to work the precious land.

The retracing of his family’s steps leads him on a trip to Auschwitz, the place of ashes, and of the great silence that punctuated the speech of his parents. Zable writes with great sensitivity and understanding, skilfully moving between history and immediacy, between myth and experience.

Comments powered by CComment