- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthology

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: The camaraderie of others

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It is curious that in a culture where physical contact and affection is far more freely expressed among women than men that the lifestyles of lesbians are thoroughly submerged. The old bigotries are still prevalent, but it seems that the factors that have placed male homosexuality on the public agenda – gay liberation and more recently the AIDS crisis – have done little to enhance the profile of lesbians.

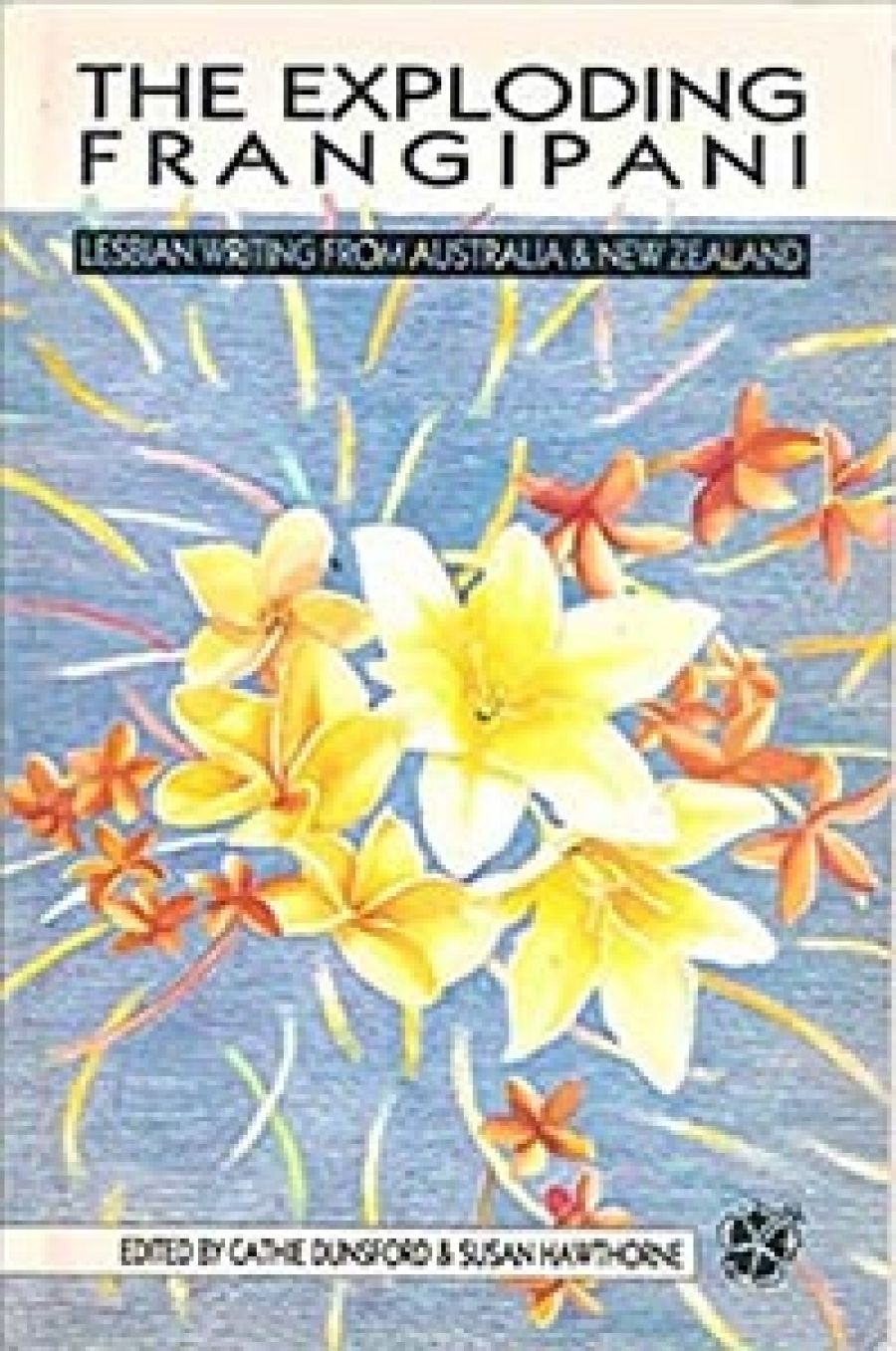

This silence, compounded by the apathy and stereotyping in the mass media, makes an anthology such as The Exploding Frangipani a potentially important book. But the overall assembly of the collection, and some of its more dogmatic contributions in particular, left me feeling unconvinced. I was uncertain, to begin with, at whom the book was aimed: lesbians, would-be lesbians, devotees of gay literature or, that elusive being, the ‘general reader’.

- Book 1 Title: The Exploding Frangipani

- Book 1 Subtitle: Lesbian writing from Australia and New Zealand

- Book 1 Biblio: New Womens Press, 149pp, $12.95 pb

It’s a problem that perhaps stems from a slight contradiction in the book’s manifesto, as defined by Cathie Dunsford and Susan Hawthorne in their introduction. On one hand they emphasise the ordinariness of lesbians, their commonality with the rest of society, while on the other they seek to delineate the unique and very special character of gay women’s camaraderie. The desire to establish lines of demarcation sits uneasily with the impulse to overcome social boundaries.

The editors have selected contributions, mostly poetry and short stories, that are both by and about lesbians. I suspect that if the criteria for inclusion had been slightly broader, following a theme which one might describe as ‘sexuality amongst women’, the argument for the ordinariness of lesbianism might have-been strengthened. Instead, the editors have drawn their material from a selected enclave which, Hawthorne and Dunsford suggest, has created a definable literary genre.

The editors write: ‘We are reclaiming our power as women, and as Lesbians. A vital part of this reclamation lies in exploring language and inventing new languages.’ Hence they align themselves with the now well-established feminist strategy which seeks to disrupt the patriarchal hegemony that becomes institutionalised in speech and writing.

Perhaps the most successful and interesting innovator represented in The Exploding Frangipani is the Melbourne-based poet Thalia. Having won a certain notoriety for her works set in concrete, she has contributed to this collection a set of ‘visual poems’ that create pictorial images from carefully adapted shorthand symbols. A piece called ‘Solidarity’, for example, employs the hieroglyphs for Solidarity, Social, Solid, and Partnership. The result is an abstracted face or pair of faces, whose gaze flows in one direction and where each figure is individual yet symmetrical.

Thalia’s work is particularly interesting because it resituates a language which has traditionally been instrumental in the subordination of women (the managerial/secretarial relationship) and yet which has also been an exclusive domain of women’s knowledge. In these picture-poems the calligraphic marking is explored and adapted, new meanings are developed, and the knowledge itself is publicly decoded in a small legend in the corner of the page.

The evocative character of these poems, their deliberate layering of meaning, furthers my conviction that quality in art, and thus the efficacy with which the writer’s thematic message is communicated, can only be achieved through commitment to the process of image-making. The sincerity or conviction of one’s political standpoint is irrelevant to the final success of the written text.

Some of the contributions in this book give little more than propagandist tirades. Eva Johnson’s ‘Alison’ protests against racism towards Aborigines, a sentiment that I thoroughly respect, but the angst-ridden manner in which it is expressed does little to sustain my interest. Susan Sayer’s short story ‘La Gnu Age or Music To Our Ears’, set at a Lesbians and Language conference, is also disappointing. The scenario is unoriginal and the attempt at verbal cleverness is a meagre substitute for genuine poetic inspiration.

The most captivating works are those that establish and follow a linguistic current, such as Wendy Pond’s evocative and haunting prose piece ‘Love Affair With Boat’ where the dreamy motion of sailing a trimaran is encapsulated in the action of ‘fishing up old images’.

Sydney writer Lou Gironde provides the most effective character study in her short story ‘Heather’, a portrait of a wild and irrepressible woman who dies of cancer. The title story, ‘The Exploding Frangipani’ by Louise Simone, gives a humorous and satirical account of the trendier aspects of the dyke scene, shifting in locale from a gym called Lesbian Ligaments to Oestrotown’s Sapphic Liquid Embroidery Co-Counselling Therapy Group.

Ngahuia Te Awkeotuku’s story ‘He Tika’ is complex in its scenario – a girl is sexually assaulted by an aunt, then seeks help from her other aunts who are loveable old lesbians. The author renders the Maori idiom most effectively, especially in the tormented monologue of the panic stricken and drunken child.

And so, The Exploding Frangipani is not without moments of enjoyment or interest, but maybe it could have crossed more and different boundaries. This might involve the creation of characters who are unlike the authors: straight women or (dare I suggest it!) even men. I say this not because l am male but because the adoption of a male viewpoint might help illuminate the nature of patriarchy which in this book is a looming but ill-defined presence.

Perhaps also the editors could have been more generous in what they consider to be ‘lesbian writing’. Now that the ‘creative’ aspect of nonfictional prose is being more widely acknowledged, some of the fine feminist scholarship that is presently being produced might have been appropriate. In this regard, Sue Chin’s autobiographical prose work ‘Sydney’ was a welcome if solitary contribution.

Comments powered by CComment