- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Diaries

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I first came across the name of Eric Michaels through a review article he published in the journal Art & Text titled ‘Para-Ethnography’. The article rigorously critiqued Chatwin’s The Songlines and Sally Morgan’s My Place, situating them as ‘para-ethnographic’ texts. It was very impressive. The note at the end remarked that ‘Eric died on 24 August 1988 after a long period of illness’. I heard later on that he had died of AIDS.

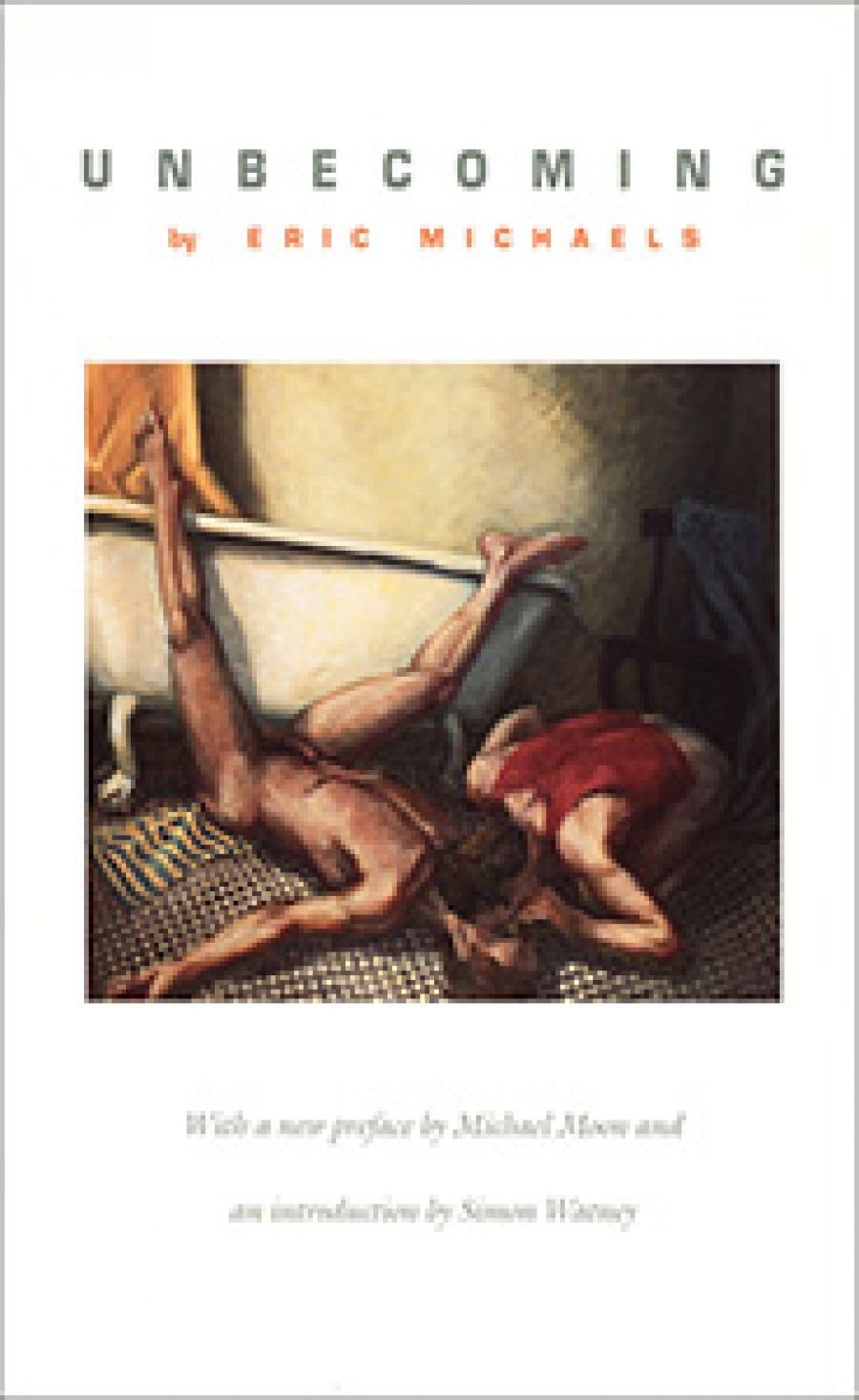

- Book 1 Title: Unbecoming

- Book 1 Subtitle: An AIDS Diary

- Book 1 Biblio: Empress Publishing, 197 pp, $19.95 pb

Eric Michaels’ name and work may only just be starting to circulate, so a very brief introduction may be in order. An anthropologist from America, Michaels came here in 1982 to take up a fellowship at the Australian Institute of Aboriginal Studies. His task was to research the impact of television and video on remote Aboriginal communities, Yuendumu in particular, in the Western Desert region north of Alice Springs. His publications include The Aboriginal Invention of Television in Central Australia, 1982–1985 and For A Cultural Future: Francis Jupurrurla makes TV at Yuendumu.

As well, he published many articles, five or six of which (like ‘Para-Ethnography’) appeared in Art & Text. Later, he got a lectureship in media studies at Griffith University in Brisbane – ‘banal, horrid Brisbane’, as he calls it in his diary. Much of his diary is written from the Infectious Diseases Ward at the Royal Brisbane Hospital.

The connection with Art & Text was important to Michaels, providing him with an appropriate, if small, audience for an anthropology that was, to some degree at least, poststructuralist, always tuned in to postmodernist debates. Michaels became an advisory editor to the journal, Art & Text Publications published For a Cultural Future, and Paul Foss, the editor of Art & Text, writes the foreword to Michaels’ AIDS Diary. Foss, Juan Davila and other Art & Text ‘names’ make up the ‘perfect guest list’ at a party thrown for Michaels in Sydney. A community of intellectuals and artists is established which Michaels both relishes and ironises. It gives him a certain local ‘celebrity’ status, even a ‘cult’ following. His reputation preoccupies him and the diary contains its share of self-promotion.

The small and contained circulation of Art & Text (‘non-mass media’) reminds him by contrast of the new communications technologies he works with, with their ‘instantaneous access to a global mass audience’. A fan of Dallas, Michaels often imagines himself connected to such mass audiences in his diary – he complains bitterly about televising policies in Australia that enable different episodes of Dallas to be run in different states, prohibiting that comforting feeling of being ‘in some quasi-mystical union with Dallas audiences everywhere’. Michaels was a Dallas fan who worked with remote Aboriginal communities; it is difficult to avoid the postmodernity of this predicament.

Indeed, a version of the tension between the local community and the global audience underpinned Michaels’ work at Yuendumu. The introduction of TV facilities into remote Aboriginal communities obviously raises problems – not least because information in Aboriginal communities is strictly regulated, whereas TV makes information appear freely available to anyone who watches it. Restrictions surrounding death are particularly affected. The dead person’s name cannot be uttered, and in every sense he or she cannot be ‘seen’. If that person is on film, then of course these restrictions are violated.

The same goes for the filming of certain ceremonies. ‘It is not unusual’, Michaels says in one of his articles, ‘to view programs containing restricted secret rituals and other violations of Aboriginal copyright’. Favouring the local against the global (hence his uneasiness with postmodernism), Michaels argued strongly for communities to determine their own cultural policies. Aboriginal visibility should be determined at the local level.

The AIDS Diary is itself a ‘local’ piece of writing made public. The effect is to make Michaels more visible than he ever was. Not everyone will thank him for this, of course. Michaels is often scathing about other anthropologists in the field, as well as colleagues, administrators and so on. In public one could never be so bitchy. The tension between the private and the public also often produces anxiety.

For example, Michaels, not known for his lack of confidence, occasionally expresses doubts about the nature of his rapport with Aboriginal people. Anthropologists aren’t supposed to admit to this. Elsewhere, and consistent with the frame of this diary as a history of Michaels’ sexuality, he becomes confessional, seeking out his own private space in the public world at Yuendumu:

I carefully nurtured a small gay video collection (safer than magazines), and used to cherish the rare occasions of privacy that provided an opportunity to jerk off to them (privacy soon becomes the most cherished and rare commodity for the modern Westerner living in most tribal societies).

This diary, stretching from September 1987 to August 1988, just a fortnight before Michaels died, is relentlessly analytic. He juxtaposes a commentary on Australia itself – its Aboriginal communities, its TV, its Bicentennial rhetoric and displays, its mannerisms – with a commentary on his own body as AIDS makes itself manifest. Michaels was a handsome man, and AIDS turns every part of his body into something other than handsome. ‘I take some perverse pride’, he writes, ‘that my cock should succumb last’.

At a particularly confessional moment (the private made public again), Michaels remarks that he feels much less self-conscious about the visible marks of AIDS on his body when he is with Aboriginals: ‘They seem a good deal less concerned.’ The identification with Aboriginal people in this diary, especially through Michaels’ remarks about his ‘rights’ in death, would be worth pursuing.

I’m aware of the reviewer’s limited role in recommending a book. One would hope, however, that Eric Michaels’ AIDS Diary circulates far beyond its intended (or imagined) circle of readers. Of course, for all its brilliance and soul-searching ideological soundness, this isn’t a sacred text. Michaels, always anxious about his reputation in the Art & Text cultural studies community, anticipated the criticism to come as his posthumous visibility grew: ‘they’ve got the axes oiled and ready, and even being so outrageously politically correct as dying of AIDS may not buy me another inch at this point.’

A recent issue of the journal Continuum is dedicated to Michaels’ work, combining a deep-felt admiration with devastating critiques. Certainly Michaels seems to have been, in Bob Hodge’s words, a ‘cowboy anthropologist’, riding into the Western Desert ‘with six-guns blazing’. Hodge goes on to expose some of Michaels’ ‘Aboriginalisms’, his unreflective use of the term ‘dreaming’, for example, and his view of ‘translocal’ Aboriginal communities as somehow inauthentic. Incidentally, Michaels’ ‘quasi-mystical union with Dallas audiences’ sits oddly with that latter suspicion of the translocal (and may sit more oddly still with the ‘dreaming’).

Michaels’ notion of ‘community’ seems to be most vulnerable here. Launching his book For a Cultural Future in April 1988, the Aboriginal activist Marcia Langton pre-empted Bob Hodge’s criticisms, taking Michaels to task for isolating the Walpiri people from the ‘pan-Aboriginal nation’.

Elsewhere in Continuum Tim Rowse fragments Michaels’ notion of community from within. Certainly in the diary there is a nostalgia for cohesive communities. And this is where Michaels’ interest in Aboriginal politics intersects with his own gay politics. The diary contains a short essay Michaels wrote about being homosexual in the 1970s before AIDS entered the arena. The end of this essay illustrates this intersection, giving gay politics a representation – a history and a future – that, interestingly enough, parallels a particular kind of Aboriginality:

But wouldn’t it be lovely if we could reclaim our lost community, our arts and our skills, of our own initiative, in response to our collective boredom. For starters, we need to take some responsibility for our own history, for conveying it to our young. It is not nostalgia. If one is going to go to all the trouble to be gay, one ought to do a more interesting and useful job of it. Models exist in our very recent past. They should be recalled.

Of course, this is nostalgia – and something more besides. While he was dying Eric Michaels went to all the trouble of writing a diary. I can’t think of a better model to convey to this journal’s readers.

Comments powered by CComment