- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Theatre

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The subtitle of this book, ‘The Revolution in the Australian Theatre since the 1960s’, is the clue to its subject and its thesis. If it is plain that Australian theatre and, in particular, Australian drama, is now an established fact, a splendid feature of the cultural landscape, this is only a recent growth.

The author has been peculiarly placed to watch this growth, to assist it and even to inspire it. Since 1974, as theatre critic for the Melbourne Age, he has seen and reviewed more than 2000 productions, more than 1000 of them plays by Australian writers.

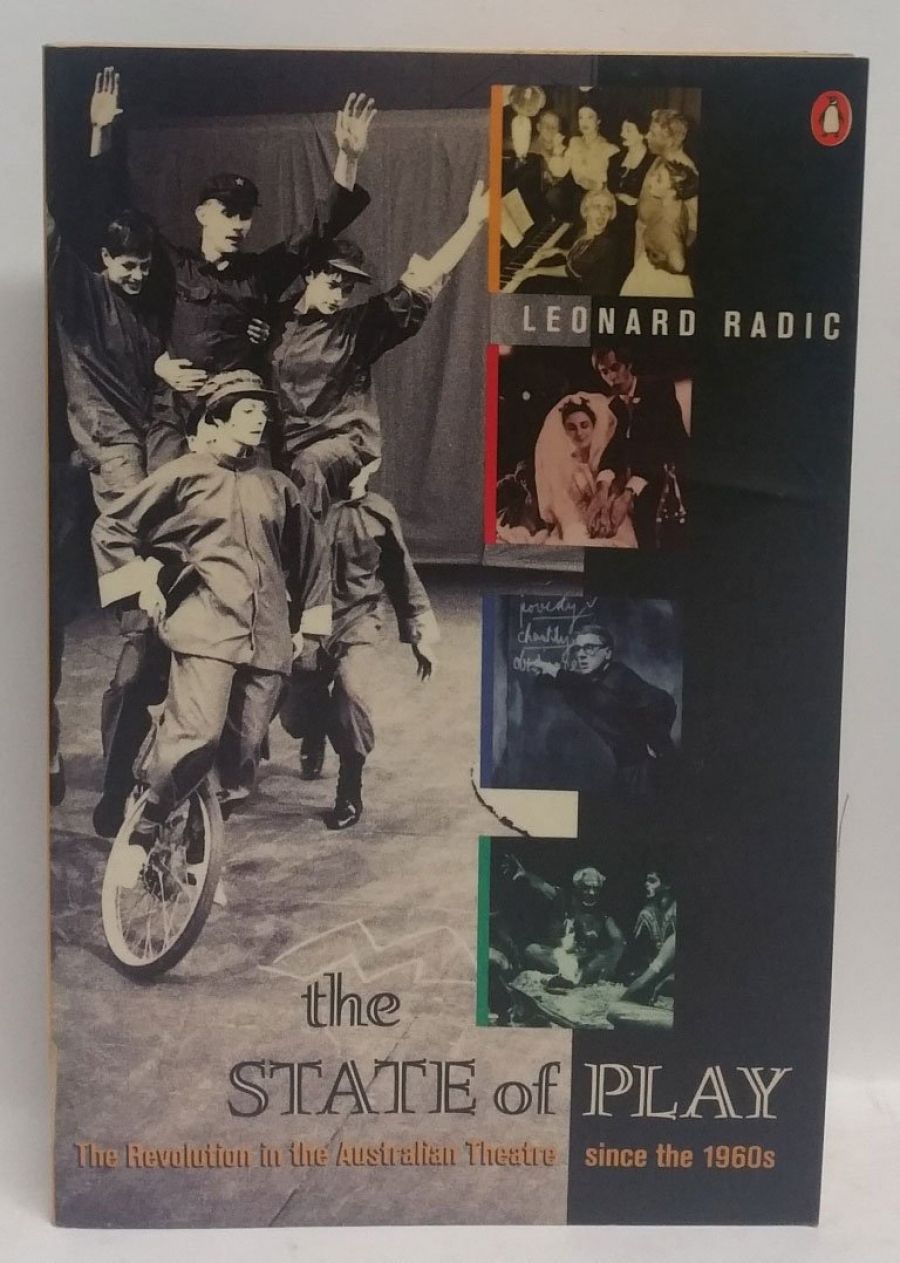

- Book 1 Title: The State of Play

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, 259 pp, $24.95pb

He himself has produced scripts and libretti for stage, radio, and opera. He has often, by the regularity of his fair-minded pronouncements, stood as a kind of sentinel to drama, ready to hear and judge all those who care to raise their voices in public. Both his critical and creative practice have helped Australian drama to ‘stand on its own feet’.

Let there be no mistake, the decision to devote one’s life to a certain thing, and not to another, is crucial. Barry Dickins attended a performance of Beware of Imitations at the Pram Factory in Melbourne in 1973 and felt his life was changed, resolving to write plays himself. That’s the kind of event from which cultures grow. Many people have made such decisions in the last thirty years, and our cultural life is the richer.

The State of Play is generally well considered, thoroughly researched, and capably written. It treats briefly the precursors of modern Australian drama (Esson, Palmer, Roland, Elliott, as well as the later Lawler, Beynon, Seymour, and White) but it reserves for its main billing for the new writers of the 1960s and 1970s. Even now it is possible to relive the audience’s delight on first seeing plays by Hibberd, Williamson, Hewett, Buzo, Oakley, and Romeril.

The discussion of writers such as these and companies such as La Mama, Nimrod, and the Pram Factory, the ventures, hopes, and dreams involved, is never less than interesting, but unfortunately rarely more. The very judiciousness, diligence, and stamina that mark Mr Radic’s long service as a critic, while they preserve him from error or unfair dismissal, seem to rob him of passion and fervour. All is dissolved in a bland, neutral analysis, and his highest praise is the laconic ‘warmly recommended’.

He shares the fault of many Australian reviewers, a dislike of enthusiasm for real pleasure in his responses and, consequently, in his choice of language. One play he describes as ‘enchanting’, and then remarks that this ‘is not a word reviewers often get to use’.

Quite. But the problem may lie in the observing eye, as often as in the object seen. Is enchantment really so rare? Without debasing the currency, some American zest or English precision would enhance his, and many other reviewers’, critiques.

His approach explicitly rules out many of the elements that go to make intriguing theatre; acting, music, direction, and choreography. For all his long acquaintance with the stage, he seems immune and indifferent to many of these essentials, and his literary (though not academic) bias is everywhere plain.

Not surprisingly, theatre that relies more heavily on these elements, where the written text has proportionately less importance, often goes unnoticed and unappreciated. His discussion of musical theatre, for instance, is proverbially inadequate. Theatre, where words, sounds, and images are presented by real people, is much more than words alone.

His critical practice is also, at times, simply inconsistent, not to say contradictory. He writes:

In the early plays [of Patrick White] the novelist and the dramatist are at war with each other, with the dramatist resorting to intrusive devices – to use the chorus or commentator to interpret the actions of the characters, for example – for which a playwright, more confident of his technical mastery, would have felt no need.

What does this mean? That a dramatist, presumably in contrast to a novelist, should not employ a chorus? Both Aeschylus and Megan Terry, to take two disparate cases, have found it a dramatic necessity to use a chorus in this way. And isn’t this division between the dramatist and novelist a little too simple?

And isn’t the use of such devices further proof of White’s non-naturalistic concept of theatre – for which he is praised a page or so later? There is something both patronising and ill-considered in this area of the writer’s thinking – some of his seemingly fair, magisterial conclusions seem little more than disguised versions of ‘I didn’t like it’.

The State of Play, then, as a study of its subject, is both assured and authoritative, and a welcome addition to our shelves. As a reference book and work of cultural history, it will prove useful, but unfortunately it lacks passion, force, and rigour.

Comments powered by CComment