- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Suspicion in two languages

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

It may seem flippant and insensitive to call this account of political threat and persecution a highly enjoyable book, but it is precisely that. Fang Xiangshu and Trevor Hay have fashioned a beguiling tale out of Fang's experiences during the Cultural Revolution and China’s political and social turmoil in later years. The product of their collaboration strikes exactly the right note. They have made no attempt to capture the idioms of Shanghai speech, but have substituted a restrained Australian colloquialism, judiciously peppered with examples of Chinese maxims, proverbs, and quotations from classic poets to give their prose something of an exotic flavour. Their narrative is constructed with great skill, negotiating expertly between the past and present, China and Australia.

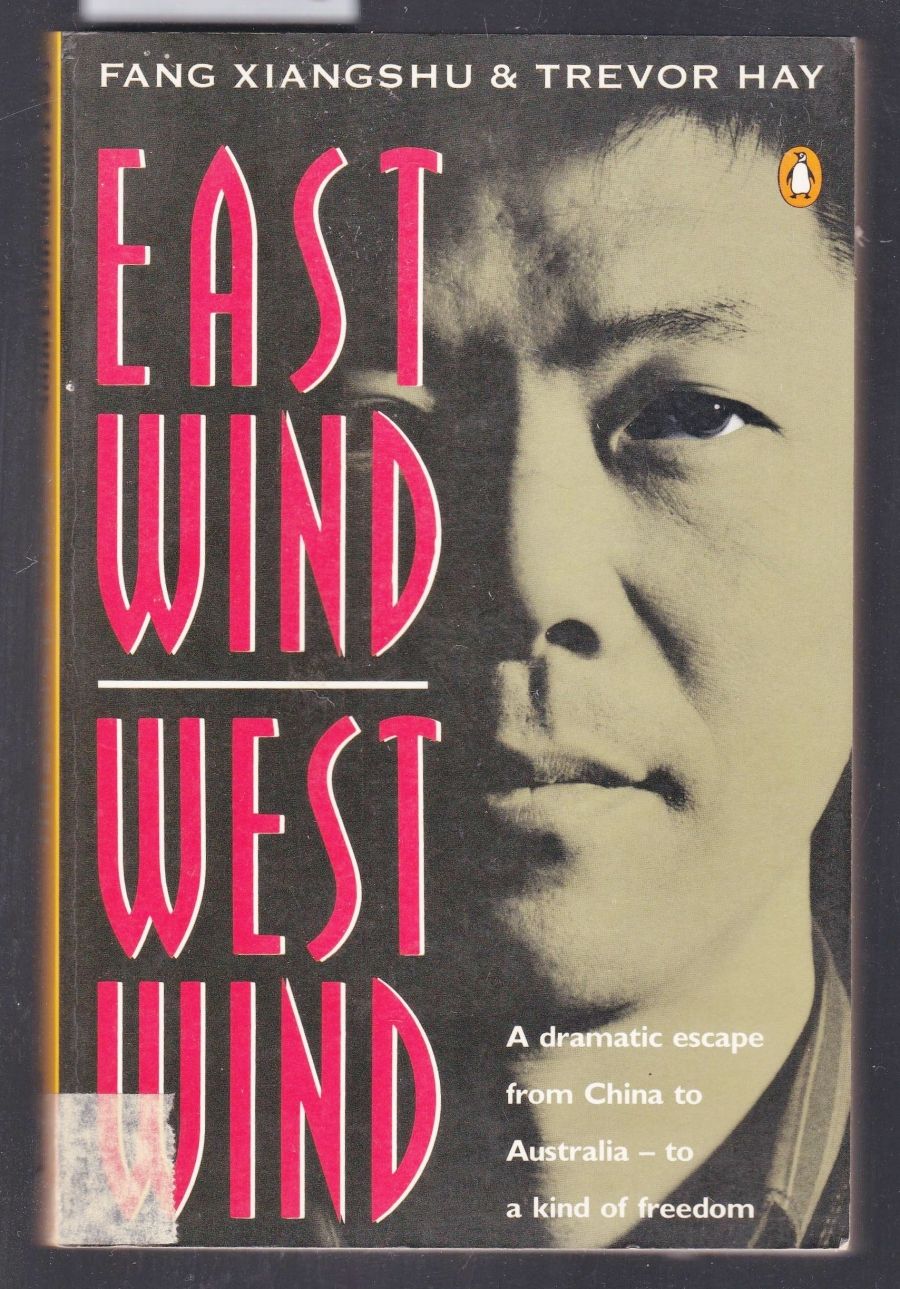

- Book 1 Title: East Wind, West Wind

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $16.95 pb

Despite its considerable literary merit, however, East Wind, West Wind will inevitably attract most attention for its subject matter and for its candid account of one person's experiences of a vengeful world. Fang Xiangshu was born in 1953 in Shanghai into a family who were to be persecuted for revisionist bourgeois tendencies during the Cultural Revolution. Fang’s father was sent off to be re-educated, as were Fang and his sister during their adolescence. A grim episode describes the hardships and humiliations the Fangs – and millions of others – had to endure in a forced labour camp, underfed, obliged to work almost beyond endurance, malnourished and constantly racked by disease.

Eventually, with the decline of the influence of Madame Mao and the Gang of Four, Fang’s lot improved. He was given a place in the Nanjing Teachers' University to study English. His linguistic gifts gained him the approbation of his teacher – a wonderful passage describes his triumph at the public entrance exaltation where his ability to count in English was admired and cheered like a high-jumper’s attempts to scale greater and greater heights. A privileged life seemed to be in store for him. He gained a teaching position in the University and then, in 1984, the ultimate accolade, the chance to study overseas – not (it is true) in America, the Ultima Thule as it were, but in Australia, which was better than nothing.

In Australia, Fang dropped the caution and reserve he (like everyone else) had to exercise in a volatile and tricky political climate. He made friends with several Australians and married a young woman from Nanjing. Then, without explanation or any warning, he was recalled. Almost as soon as he arrived in Nanjing he realised that he was in disfavour. Cold-shouldered by his colleagues, denied accommodation, given no teaching, he could find no reason or explanation for this swift change in his fortunes.

As often happens, though, Fang’s troubles stemmed not from some major misdemeanour of indiscretion, but from suspicion, from malicious denunciations by envious or ill-intentioned colleagues and superiors, and from the extreme sensitivity of all brutal regimes towards what is considered unorthodoxy.

The closing sections of the book contains an engrossing account of Fang’s attempts to discover the nature of his misdemeanour, the source of the charges laid against him and their likely outcome, for which that clichéd term ‘Kafkaesque’ is inevitable. East Wind, West Wind ends as Fang, with that remarkable resourcefulness victims of oppressive regimes are obliged to learn, effects his escape to Australia. There he becomes entangled in lesser, though no less, distressing, dangers and difficulties until at length and after much bureaucratic obfuscation and even malevolence, he and his wife are granted resident status in 1990. ‘What have I learnt of democracy and justice?’ he asks in the final paragraph:

What can I say to those still dreaming in China, as I once did? I still believe that the differences between China and the West are reality, not just dreams. But my nights are still troubled. Not so long ago, I had a nightmare, in which Red Guards paraded me through the streets of Shanghai, wearing a huge wooden collar like criminals wore in feudal times. I was kicked to my knees in front of a screaming mob, and made to confess my crimes. But my crimes were confessed in English and I had to bawl out that I was a ‘prohibited non-citizen’ and a ‘flagrant liar’.

East Wind, West Wind is the story of modern China told from the perspective of one of its victims who had been more fortunate than many others. Fang Xiangshu managed to escape; he managed to persuade the Australian authorities to allow him to settle here; he has found friends and supporters such as his co-author Trevor Hay, whose own brush with authority – the result of a stoush with the police over an alleged driving offence – provides an ironic undercurrent to this tale of political persecution. The book is therefore a valuable documents not merely of recent Chinese history but also of our own society’s responses to the upheavals to our north. What is has to say should command the attention of all those who imagine that complex and confused situations and relationships may be solved by means of slogans or dogma.

On another level the book speaks of an all-too-familiar world. Though the setting of Fang’s tribulations is China, his predicament is that of anyone who has experienced life in a totalitarian regime. One episode stirred a long-buried memory for me. Fang describes his parents’ feverish attempts to obliterate all signs of their ‘bourgeois’ past – books, letters, pictures – as the Red Guards are advancing on their Shanghai flat. I remembered the day in 1942 or 1943 when my parents stuffed piles of books and documents into the great tiled stove of our house outside Budapest because Hungary, until then only a half-hearted participant in the madness of the time, was falling under the domination of Nazi Germany.

As with my parents, or with millions of people in wartime Europe, in Pinochet’s Chile or, no doubt, in the present-day remnants of Yugoslavia, Fang’s experiences reveal the horror of such worlds. The brutality and persecution are, of course, well known and have provided our century with familiar infernal icons – icons that reappear in this book with commendable restraint. East Wind, West Wind records, with equal restraint and with a nice sense of irony, another, less spectacular but no less dangerous aspect of such regimes – the vain, at times bumbling but always malevolent petty officials, grey bureaucrats, time-servers, and opportunists who flourish in such circumstances.

There are some marvellous accounts here of the arbitrary power such people are able to exercise – the truth of King Lear’s remark that a dog’s obeyed in office is fully confirmed in these pages. And yet there is one little note of hope – just as there were instances of hope for those of us who experienced similar dangers half a century ago. That hope is not so much that truth and justice will prevail, it is rather a recognition of the inefficiency of some of those pompous bureaucrats and backyard dictators. How Fang managed to escape from China provides a wonderful illustration of the way such functionaries contrive, at times, to defeat their own purposes. In that, there is at least a small grain of comfort.

Comments powered by CComment