- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthropology

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The title of Gillian Bottomley’s lively study addresses both the major theme of migration and her own position as an academic anthropologist. Bottomley targets specialist studies with hard and fast disciplinary categories and attitudes and rejects the tone of impersonal scholarship which such works frequently adopt.

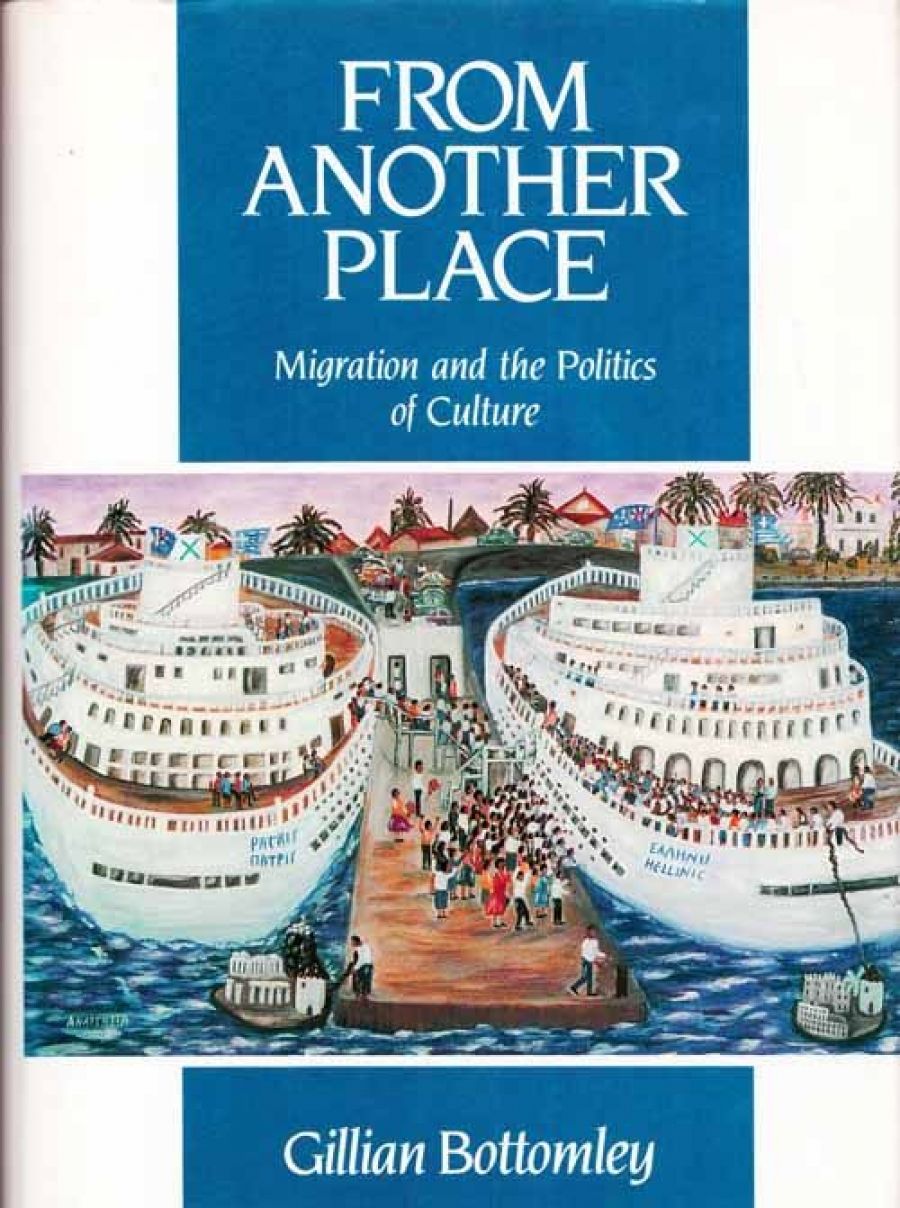

- Book 1 Title: From Another Place

- Book 1 Subtitle: Migration and the politics of culture

- Book 1 Biblio: CUP, 192pp, $39.95 pb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/yRP2E2

Bottomley is an Associate Professor in Anthropology and Comparative Sociology at Macquarie University with an extensive record of research and publication in Greek-Australian studies. She is uneasy about her formal academic label and claims a set of experiences that nourish a different self-understanding. The other Bottomley is a female student from a rural, ‘poor-white’ background. This is her different place.

It is a hazardous business to cast oneself as the creative misfit in the sterile world of academe, a figure radically different from ‘most academics’. Academe is full of people who see themselves in just these terms – brave, feisty souls pitting themselves against the powers and refusing to fill in forms by the due date. Where would staff clubs be without them? While I applaud Bottomley’s motive in declaring her hand, the self-portrait is too lightly drawn, too lacking in ironic detachment and, finally, too self-serving to achieve its purpose. More would have been better, including, perhaps, more on the ways in which universities foster some people and inhibit others.

Bottomley’s approval of the creative role of non-specialist ‘outsiders’ is also apparent from her observation that ‘literature is necessary to sociology’. She commends Athol Fugard, Nadine Gordimer, Salman Rushdie, ltalo Calvino, and Patrick White among others, for the light their work throws on migration and the politics of culture. While these writers are pushed to the front of the queue of lively minds whose influence is generous1y acknowledged, their writings are not subject to substantial analysis. They form part of the cultural capital drawn up against the hardline specialist.

The core of Bottomley’ s book, the product of twenty years of research and teaching on migration, culture, ethnicity and racism, lies in her sustained examination of the meanings and usages of the term culture for students of migration. Linked with this project is an argument against the separation of class, gender, and ethnicity as if they were distinct, unrelated categories. Throughout her book Bottomley demonstrates the ways in which they interpenetrate.

Bottomley’ s discussion of culture is particularly illuminating. A quote from Eric Wolf pinpoints some of the historically specific meanings of culture in a manner that Bottomley approves. She quotes Wolf as follows:

Once we locate the reality of society in historically changing imperfectly bounded, multiple and branching social alignments, however, the concept of a boxed, unitary and bounded culture must give way to a sense of the fluidity and permeability of cultural sets.

Towards the end of her book, Bottomley considers culture in its Australian, or Australianist, context. She is critical of the failure to give immigration a significant place in studies of nationalism and national identity. She may be right in insisting that it has been ‘surprisingly ignored’, but she, in turn, does not mention James Jupp’s The Australian People, a major project and a serious attempt to give immigration its due. Bottomley’s brief, but pointed, criticism of Australian studies for overlooking non-Anglophone people flows directly from her rejection of boxed and bounded understandings of cultural identity. Her book charts interesting territory for those within Australian Studies who wish to explore Australia’s cultural interaction with the world beyond our shores.

Fresh approaches and new subject matter are particularly evident in chapters which examine dance, music and the dowry in the middle section of the book titled ‘Practising Cultures’. Bottomley asks: ‘How can dance (and mime) ‘speak’ to us about abstractions such as ethnicity and identity, about interpersonal relations or the construction of subjectivities?’. And in the process she also asks why dance and mime have been downplayed an muted in examinations of migration, ethnicity, and culture.

The central guide to this study, the person to whom the author refers most often and most approvingly, is Pierre Bourdieu whose Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgement of Taste looms large. But Bottomley has ranged widely in her reading and commends illuminating texts with enthusiasm. She refers to Jacques Attali’s Noise: the Political Economy of Music as an ‘exhilarating and revealing’ study’, while Jane Cowan’s Dance and the Body Politic in Northern Greece is a ‘superb study’. And so on through many books and articles.

It is one measure of a good book that it can shift our perceptions and another than it sends the reader galloping to the library in search of exhilaration. From Another Place scores well on both counts.

Comments powered by CComment