- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Anthologies

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

A few years ago, there was a great song on the radio, a song about remembering riding with an assortment of brothers and sisters in the back seat of the car. I don’t even recall the name of the song, much less the name of the band, but there was a line in the chorus that used to wipe me out: ‘And we all have our daddy’s eyes.’

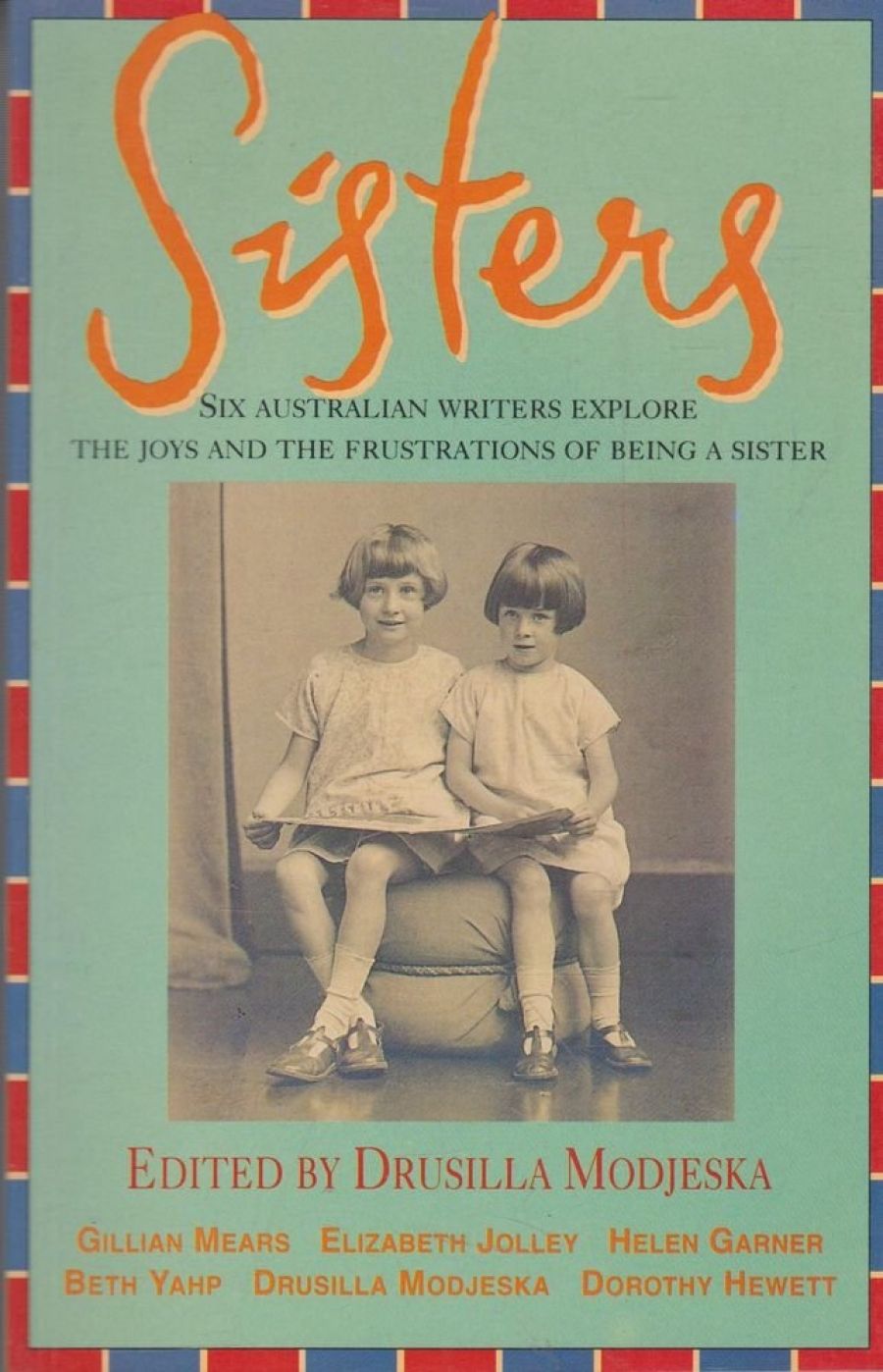

- Book 1 Title: Sisters

- Book 1 Biblio: Angus & Robertson, $16.95 pb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/nqJNa

So female siblings, sisters, exist in a no-man’s land of sameness, and difference where the acknowledgment of and pleasure in resemblance coexists with sometimes, and sometimes necessarily, violent assertions of uniqueness and autonomy. ‘There is something ecstatic, brakeless,’ writes Helen Gamer of herself and her four sisters, ‘about the way we laugh together ... laughing together is a way of merging again into an inchoate feminine mass. (Again? When was this previously the case?)’

Dorothy Hewett’s, on the other hand, is a powerful vision of difference:

In your brown velvet dress with the lace collar you looked like a gypsy. That was how you went to the RSL fancy dress ball, dressed as a gypsy. I was a fairy in spangles and wire wings with a silver cardboard star in my hair.

Each of the six contributors to this book is one of a number of sisters. Helen Gamer (the only one who also has a brother), Drusilla Modjeska, Dorothy Hewett, and Elizabeth Jolley are all firstborns; Beth Yahp is the second, and Gillian Mears the third, of four. They were given, says Modjeska in her introduction, ‘a simple brief’:

to write about the vexed relationship between sisters in any way, in any form, they liked: essay, fiction, autobiography ... this book is less a collection of case studies on the vexations of sisters than exercises in writing, in telling, in remembering.

Much is implied by those suggestive variations on the word vex, with its origins in the Latin word for jolt and its echoes of hex and vixen-witches, foxes, something female and hypernatural wielding uncanny kinds of power, kin but other. The tension and intensity generated in and by all six of the pieces (even Jolley’s, the gentlest and least equivocal) are sometimes frightening, and it’s to do with the nature of the sister relationship, oxymoronic and inescapable. You are the same as and different from these creatures whom you love and hate and will never elude: ‘women’, as Gamer puts it, ‘for whom I have feelings so dark and strong that the word love is hopelessly inadequate’.

‘Sisters are good at punishment,’ writes Modjeska in her introduction, ‘and they have long memories’. Sisters invent each other’s memories, and invent each other in memory, and sometimes the mark of memory is etched in skin and bone. ‘There is a long scar’, says Beth Yahp, ‘by her nose and lips that I put there, neither hesitant nor thin’. ‘We scar easily,’ says Gillian Mears, ‘and remember everything’.

Some of the similarities of content among the six pieces are remarkable; it’s as ‘exercises in writing, in telling, in remembering’ that they vary most. The mother of the ‘Mears girls’, and her approaching death, is at the centre of Gillian Mears’s ‘The Childhood Gland’, and the writing circles meditatively around that focal point. Beth Yahp’s piece is called ‘Houses, Sisters, Cities’ and uses notions of space, cultural difference and cosmopolitan sensibility to compare two generations of sisterhood. Helen Gamer’s ‘A Scrapbook, an Album’ combines a number of imaginative technical moves to do with polyphony and collage. Drusilla Modjeska explains in her introduction that in writing her piece, ‘The Cuckoo Clock’, ‘my strategy of avoidance was to press into service once more the parallel family, not mine, yet like mine, that I invented for Poppy’.

Dorothy Hewett slides back and forth between ‘straight’ autobiography and an extremely powerful and convincing horror story concerning ‘The Darkling Sisters’. Elizabeth Jolley’s ‘My Sister Dancing’ begins in episodic memoir mode, moving unnoticeably towards a moment of family crisis. What gradually becomes apparent is the difficulty of articulating sisterhood at all, much less telling any kind of truth about it. ‘The conversations on which this essay are based, writes Garner, ‘have stirred things up … I feel panicky. We are five sisters and it doesn’t seem right to name us. The others wouldn’t like it.’

The two women I quoted at the beginning of this review appear to be speaking different languages. One of Drusilla Modjeska’s achievements in her various projects over the last ten years has been to develop ways of saying both of those things, both of those kinds of things, in, so to speak, the same sentence. Like each of her previous books – Exiles at Home, Inner Cities, Poppy – this one concerns itself with complex questions of language, gender and memory. But she has never succumbed to the temptations of what Judith Brett has called the ‘bureaucratisation of writing’ and Sisters, like all her other work, constructs a heterogeneous readership with endless good and variant reasons for reading: an appetite for gossip or theory or story or style, or even just a desire for small particular illuminations of that dark mad camp, the family.

Comments powered by CComment