- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Seduced in the same old way

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Lyn Hughes’s One Way Mirrors begins with a white horse impaled on headlights. It’s autumn, ‘the stars look cold and pinched’. You know it’s going to end badly and it does, mostly.

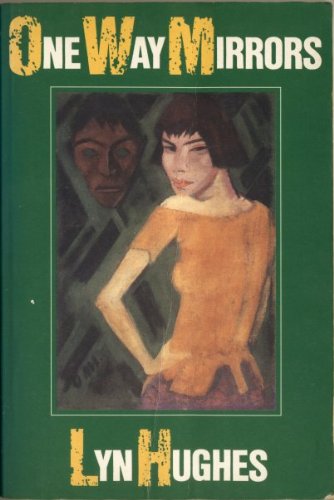

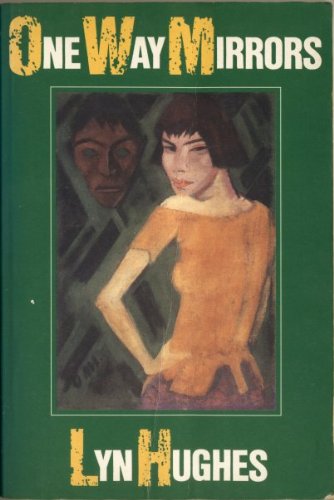

- Book 1 Title: One Way Mirrors

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $14.95 pb

- Book 1 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 1 Cover (800 x 1200):

Rosemary Williston, a childless but fairly comfortably-off suburban wife in Johannesburg, feels herself ‘jaded ... growing old’ as she approaches forty. David, her husband, seems to make love ‘more for comfort than lust’. Looking for some new meaning for her life, Rosemary begins drawing classes given by the independent, attractive, Louise Tolley. At their first meeting, ‘Rosemary’s thumb caught on a brooch above Louise’s breast ... It drew a bead of blood.’ Later, having ‘eased the legs apart’ of several easels, Rosemary ‘broke a nail before she felt the supportive strut give way’. Sexual attraction and pain are both suggested by these images and certainly encountered in the following affair between Rosemary and Louise.

For Rosemary it’s a new, strange and exhilarating experience. But for Louise it’s just another relationship, time out from her political activities with a black revolutionary group. Rosemary is, in a way, a mid-life innocent but Louise is a kind of sexual predator and eventually goes off with someone else (isn’t that just the way?). Rosemary is left to try to renegotiate her relationships with her equally unhappy women friends and her tolerant but damaged husband and as well decide if she wants to be involved in any further politics.

While only a partial account, this does suggest something of the sitcom romance quality of One Way Mirrors. The characters, especially Louise, are stylised, perfunctory and often stupid. Louise becomes a shallow and unsurprising adventurer although at first she was interesting, ‘a vicious beast ... always causing pain’. She is all too quickly subsumed by the conventions and power roles of popular romance. Rosemary, too, deteriorates from being an ambiguous central focus for a number of complex tensions (childlessness, social status, wife) to become drippy and querulous – a classic ‘helpless female’. And the male characters are ineffectual or boorish.

There are constant comparisons with male dominance which seem defensive: ‘Men are such a cross and yet we swear they’re our salvation’; “Much better than a cock”, she sighed, rocking high above her.’; ‘... her thighs and muscled breasts were leaner than a boy’s’.

One Way Mirrors sets out to challenge conventional notions of heterosexual desire in a relationship, especially the inscribed powers of male sexuality. As such, the sexual scenes are described with a fine sense of the detailed wonder of arousal. (But is there really any qualitative difference between the sexual excitement of gay and heterosexual partners? These passages provide much evidence to the contrary.)

Most difficult though is the political dimension with which the novel plays. Louise’s soliciting of Rosemary is a seduction into politics (we realise later) but it seems an afterthought and is unconvincing. Louise’s political activism seems part of her exotic attraction, another dimension of plot interest, background, rather than integral to the situation in South Africa. Her interrogation by the police seems unreal and awkwardly polite – it’s hard to believe they can’t cope with questioning a woman whose love letter to another woman they have read. It’s a bit coy.

There are, however, moments of fine writing, as when Hughes combines – in one paragraph –a sense of what is seen and felt and imagined; as for example in this scene of an accident:

The policeman’s foot bumped the dead man’s boot and set it rocking. He is dead, she thought. She gathered colour for Louise. The cropped trees with their insufficient shade. The people crowding underneath. The policeman’s hand, brushing to and fro against his gun, bulging in its scuffed brown holster. When Charlie was little he had played with his genitals like that...

Also the sense of Rosemary’s husband’s inarticulate pain is well done. As is the account of the disintegration of her ‘manic-depressive’ friend, Claire. The puzzling sense of domestic and sexual politics when Claire’s husband and her doctor seem to be in collusion is palpably disconcerting.

One Way Mirrors is, on the whole, a bit of a mixed bag. (Aren’t most mirrors one way? Perhaps it’s meant to indicate the impossibility of escaping from conventional social constructions.) It can’t seem to make up its mind whether it wants to be a feminist novel, a romance, a political or a post-colonial novel. Hughes’s best work is still to come.

Comments powered by CComment