- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Where women lead, men generally have the sense to follow. Eventually. Feminist fiction, lesbian fiction have developed ahead of gay fiction in Australia. This is one of the many ideas acknowledged or explored in Dennis Altman’s welcome addition to literature about homosexual relationships.

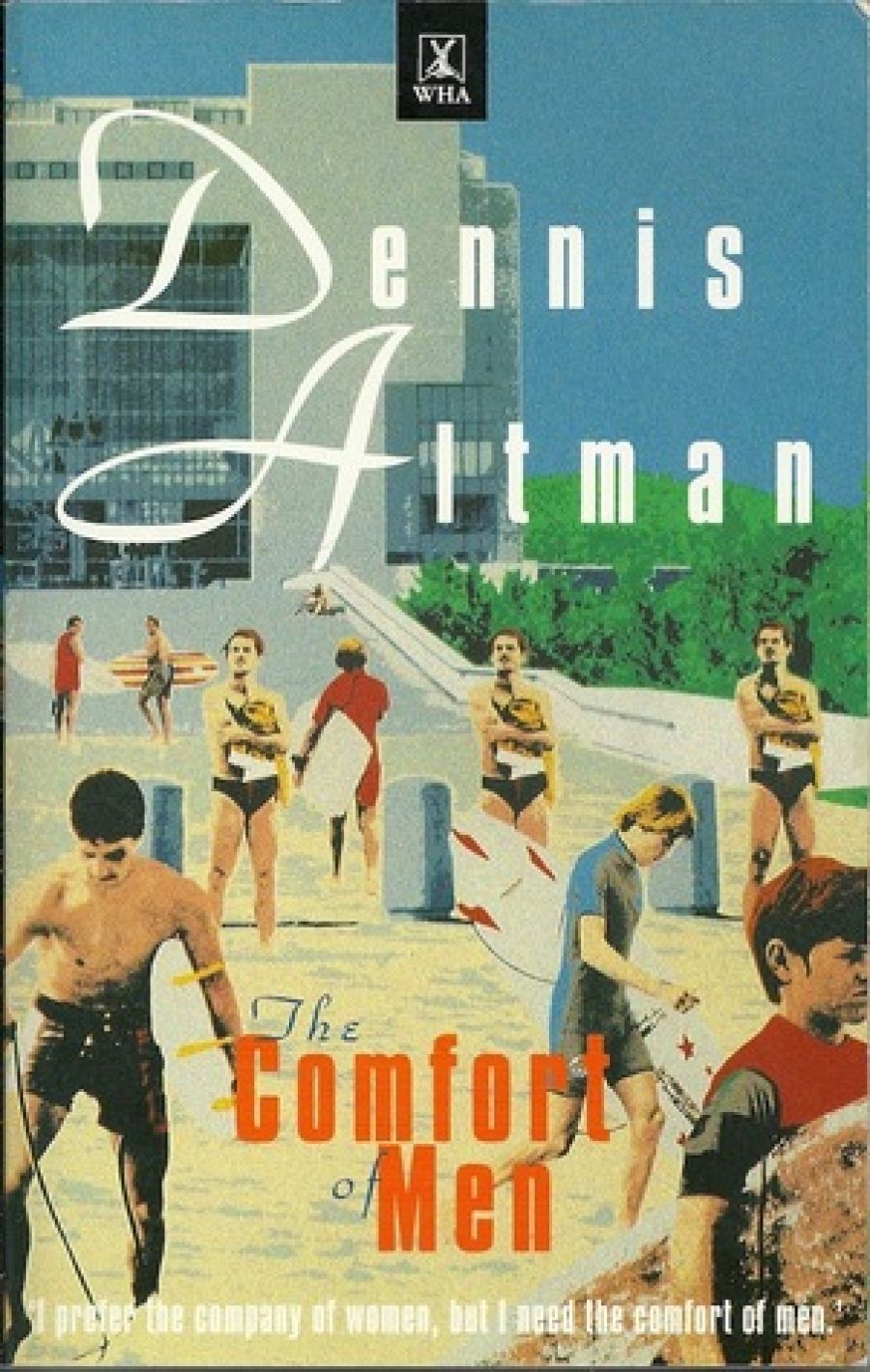

- Book 1 Title: The Comfort of Men

- Book 1 Biblio: WHA, $19.95 pb, 0855614196

The narrator is Steven and he looks back from the present and tells the story of his past to his lover, James, who is dying of AIDS. Steven’s story involves that of his gay friend, Gerald, and the life of two highly individual women, Hester and Susan. Much of the novel is set in Hobart, where in the last flatulence of Victorian moralism and social conservatism an increasingly successful Independence movement is led by a man appropriately named van Gelder. Tasmania is presented as the fig leaf covering Australia’s prudery and hypocrisy, whereas Sydney and Melbourne become for the characters the unveiling of the possibilities of personal, sexual, and political freedom.

Altman is grimly convincing about ‘a new and independent Tasmania’, ‘held together by respect for the eternal verities of the Bible and the British way of life’. This is a society where AIDS sufferers find a new virus in the disintegration of personal freedom, for they must prove that their illness was ‘innocently’ acquired or they will forfeit their civil rights. Altman is sadly compelling about the Neo-Puritan, no-saying 1990s.

Yet this novel is also warmly optimistic about the possibilities of some human relationships. Particularly strong is the portrait of the narrator, ‘terrifyingly naive’, an ‘outsider’ who looks back in peaceful wonder at his ‘sense of confusion and terror about my sexuality and the fact that I both disliked being homosexual and could not imagine any other way of being’. Altman shows himself to be an assured storyteller as he moves this narrative of ‘self-hating’ and ‘social stigma’ into the story of the Tasmanian Independence movement. He indicates how fragile the fabric of our society is and how repressive and demagogic politicians of any persuasion can be when the light on the hill turns out to be the magic lantern of their own personal ambitions. Altman is affirmative, even romantic about both the 1960s and homosexuality. However successful this novel is, I doubt if it will be listed in Who’s Who as the favourite reading of politicians in either Canberra or Hobart, which indicates its political and imaginative force.

Powerful as this novel is in the portrait of Steven, whom much of society sees as justly suffering the loneliness of the long-distance sinner, it is also strong in its account of two women who are outsiders because they are women who refuse to pin their hopes to the Hill’s Hoist of female stereotypes.

Here, I think, there is a structural weakness in the novel, as Altman wants to decorate his cake and eat it too. On the one hand he asks the reader to believe that Steven is reconstructing the lives of Gerald, Hester, and Susan from observation, letters, conversations. The narrative gets to points of intimacy and detail in their lives where it is hard for the reader to keep suspending disbelief. On the other hand, James, to whom the story is told, remains elusive.

With regard to this second point, Altman himself refers to Scheherazade telling her stories to King Shahryar, who remains another forgotten politician who happened to be good at listening. But we remember Scheherazade, as we remember Steven from this novel, but not James. Steven also tells us that he needs to accept his past in order to begin his present grieving. I have no quarrel with any of this, but merely note that the process of dying remains the last taboo of contemporary fiction. Thus I read this novel with a certain sense of authenticity denied and confrontation avoided at particular moments. On the question of authenticity, I suspect that some readers will note with me that in this novel lesbian and heterosexual relationships are unfulfilling and love is presented as fulfilling only in some painfully achieved gay relationships.

I emphasise that these are minor hesitations about an intelligent, forceful, and moving novel. I also have a few qualifications about Altman’s use of language which is generally precise and imaginative. Just occasionally it gets lost in its own lushness or clatters into cliché. A morning that is ‘hot, sweaty, sultry, soggy’ and that carries ‘that sticky, slightly rotting smell of Sydney’ is sweating too many adjectives. Van Gelder has ‘piercing black eyes’, Menzies has a ‘stentorian’ voice, a would-be lover has ‘saturnine dark looks’, the past was now ‘literally’ dead, and Steven has ‘thick, curly, russet hair, the colour of the desert at dawn’.

The reader has to accept the fact that Steven is a romantic, who is also at times witty and wry. Altman tells this story with verve and confidence. In extending the personal and the sexual to the political, he challenges us imaginatively and intellectually in a way that is emotionally rewarding and memorable. The Comfort of Men is a significant step forward for a writer who has already moved a long way in developing contemporary Australian consciousness.

Comments powered by CComment