- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

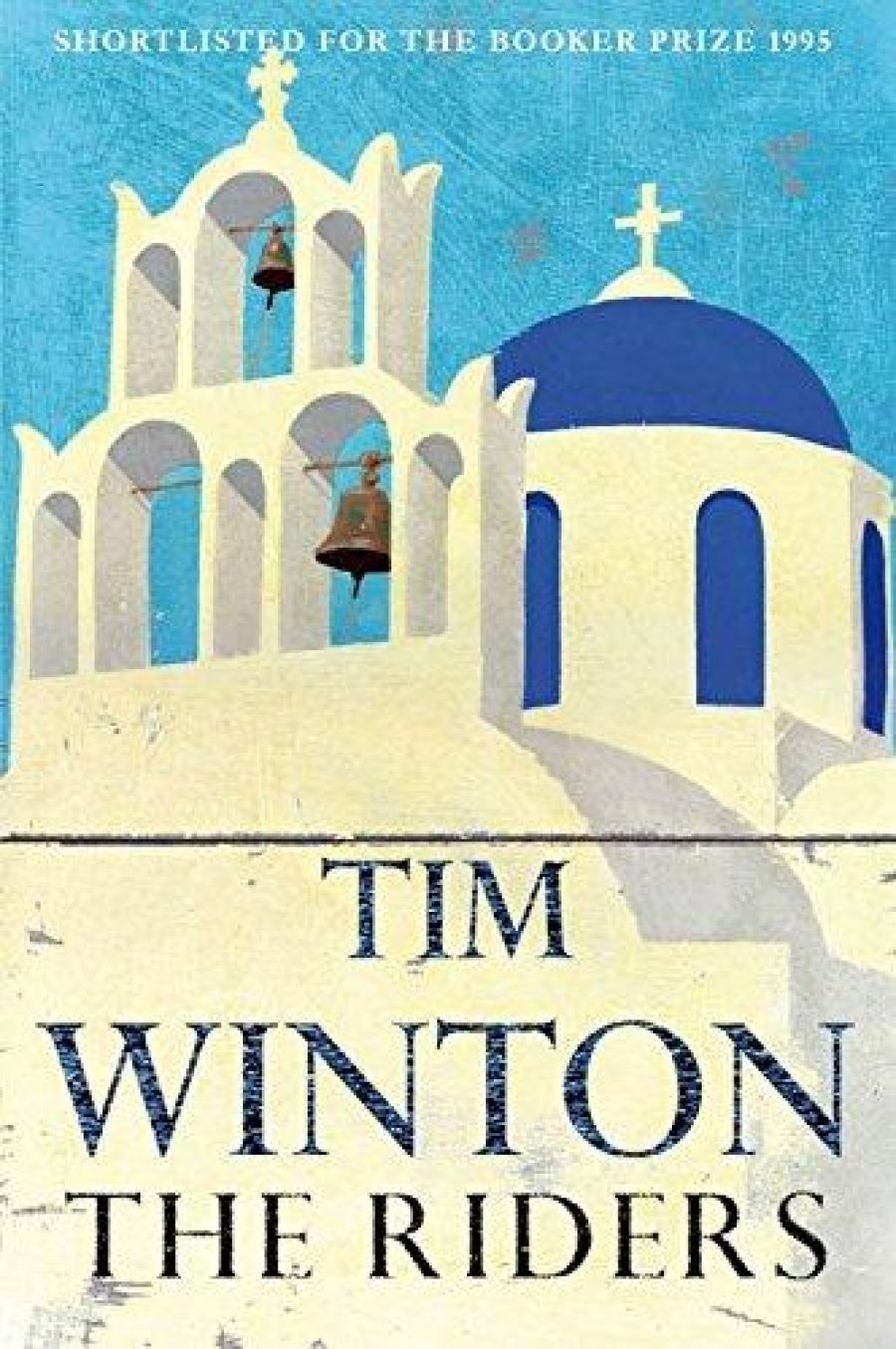

- Article Title: Riding to hell on Tim’s back

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Okay I’ve just finished reading Tim Winton’s The Riders. I’ve scribbled notes on pages all the way through, but I don’t want to go back and consult them. Who wants to return to hell?

- Book 1 Title: The Riders

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, $35 hb

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/Gjggxk

Frederick Michael Scully (‘Scully’ to his mates, his one-night stand, his seven-year-old daughter, Billie) refurbishes a ruined cottage in Ireland, expects his family to join him, discovers his wife has left him, and spends the bulk of the novel chasing her across Europe (Greece, France, Holland) with his increasingly scarred daughter in tow. And his search continues to the last page.

It’s a nightmare. It’s hell. (I know I’ve said that already.) It’s the return ticket on all the paradigmatic journeys that make up the Australian male tradition. It’s a transportation to the convict settlement of the male mind; it’s an expedition to the dead male heart; it’s a landing on the Gallipoli Aussie men have made of marriage.

Okay. Scully’s wife, Jennifer, is lovely. She has legs that speak all languages. (All male languages, at any rate.) She wants to be a writer, or a painter – anything of ‘genius’, Scully thinks. In male language we are told what she is. In female language, it seems, she wants to know who she is. There’s a difficult border here. It’s obvious she just wants to be herself, but Scully can’t handle or comprehend that. It wipes the Mercator lines off his map.

Scully is a mass of inferiority complexes – working-class, non-intellectual, antipodean. But worst of all is his Quasimodo complex. He thinks he’s ugly. He carries a huge hump of molten fears and guilts and recriminations to pour on the world – especially to pour on Jennifer. But everyone else gets splashed with the acid too, especially his devoted daughter.

Need I go on?

Scully is jealous. Scully thinks he is trusting and victimised and misunderstood. Scully fantasises the worst scenarios about his wife. Scully blames women for everything. Scully reckons he is in hell. Scully is an obsessive madman. Scully inflicts monstrous traumas on his loving little daughter. Scully wants to kick a woman. Scully then fucks the same woman for the price of a train ticket.

Need I go on?

This is a wild novel, an awful harrowing of the hell of Australian male consciousness. Tim may have been diving in the shallows in past novels, but this is the real thing – the dive to the bottom, the bends.

Women will hate this novel, I believe, because the novel seems to hate women. Men will be scared to tears by it, because it tells ugly truths.

Okay. I’m talking to males now. What do we do in the post-feminist world? What do we do with all the Australian male culture we were brought up on? How do we cope with knowing that all our knowledges/ attitudes/ certainties/ presumptions/ understandings/ orientations are gone for nought, are struck from the record, are no longer currency?

We have to look in the mirror with Scully, I’m afraid. We have to see what a hash he makes of everything. We have to acknowledge that our mates (the female ones, you idiots) will never be found where we think they are no matter how hard we search for them there. They’ve gone. They’ve moved on. They’ve found a better place. We don’t define them, or where they stand, anymore.

And our love/hate-crazed representative, Scully, searches wildly for them for us. He goes to Hydra where the classic Johnston-Clift relationship happened. He scours that territory. His wife is blameless there. He goes to Paris where the classic Frenchman threatens. There is nothing to be uncovered there either. He goes to Amsterdam as well, right into the maw of the celebrated European sex supermarkets. He finds nothing. No alien stain on a sheet anywhere. But he does get hit over the head with a hard, outsized dildo.

Silly bastard.

Okay. I’m talking to females now, if I may. I don’t expect you to listen, having listened to bullshit for so long. But perhaps Tim is the most honest of us (males). He’s confessing on behalf of us (males). He’s showing what dills we (males) are. But also he’s saying that there are reasons.

Okay. Now I really know you’re not listening. But the riders don’t want to be riders anymore. (Not the intelligent ones, anyway.) We want to be ridden too. We want to share the riding. We want to find, at the end of the search through the maze of cultural constructions, an equality – a new place. We don’t want that Eliotesque return to the point from which we were started.

Perhaps I should have consulted my notes, after all.

My notes said (I think) that The Riders is a marvellous examination of the relationship between a screwed-up father and his got-it-together seven-year-old daughter. Billie is a superb creation in the mould of Helen Garner’s Poppy, in The Children’s Bach. Her viewpoint, when used, keeps tipping the novel back from the brink of insanity.

My notes said (I think) that Tim is a brilliant viewer of landscapes and seascapes, no matter which hemisphere he applies his embracing senses to. His countrysides roll out from the page and plant themselves firmly beneath your feet; his tides wash past your ankles.

My notes said that Tim’s language is rich and pearly as fresh-landed gouts of hot sperm. (Maybe my notes didn’t say this. Maybe I’m just remembering the regular references to Scully’ s balls. Scully reacts to the world a lot through his balls. Silly bugger.)

And I’m sure my notes said a lot else besides.

It’s a hell of a novel. It’s probably a hell of an important novel. You find your own way through it.

Comments powered by CComment