- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Against the grain

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

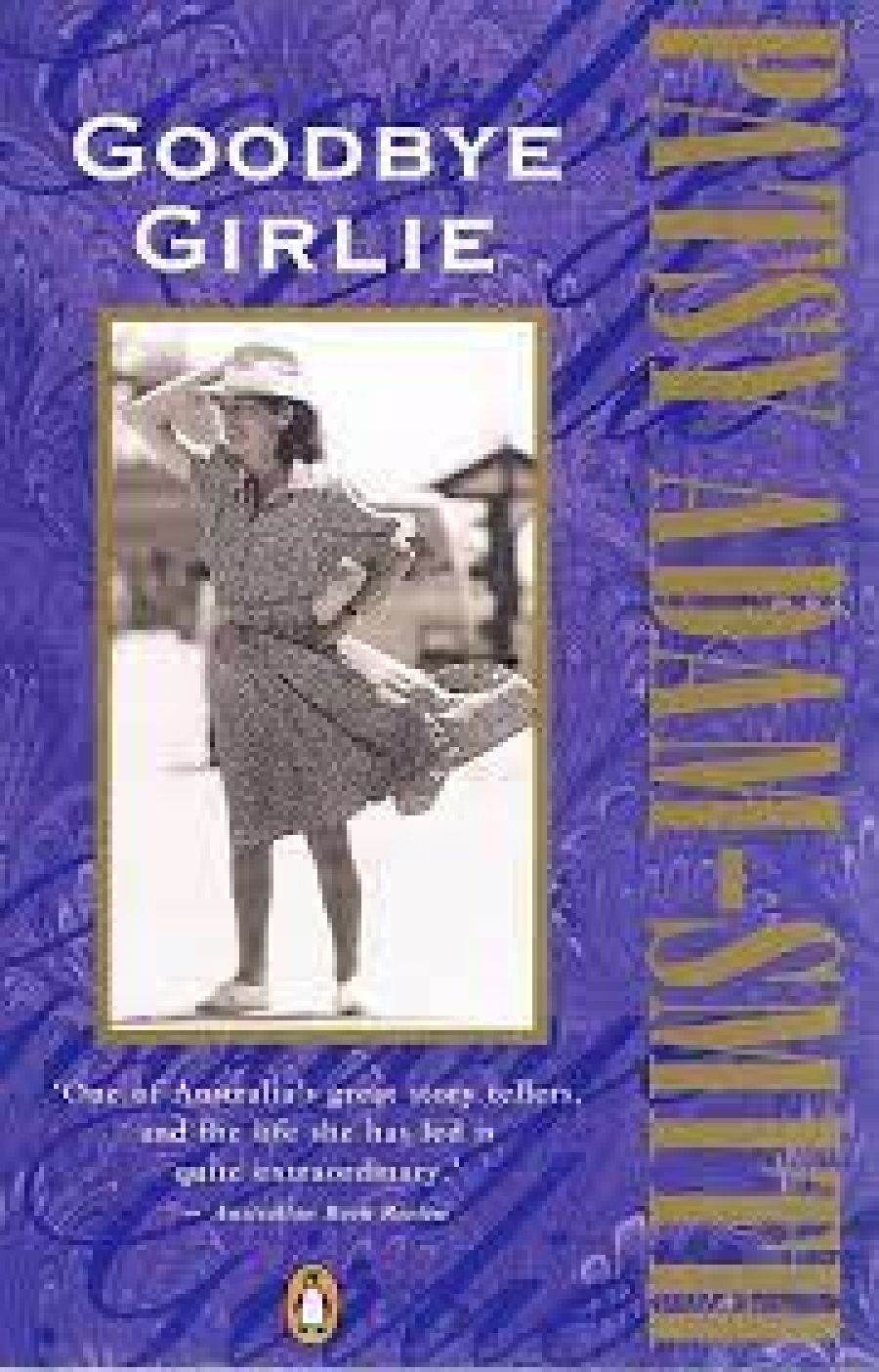

It’s a clever and provocative title that Patsy Adam-Smith has chosen for her autobiography. She is a woman who has said many ‘goodbyes’ in her rich and adventurous life; and she is of an age and disposition where ‘girlie’ is heard as an endearment, not a put-down. Patsy AdamSmith is one of Australia’s greatest writers, although you will rarely hear the literati or the academics say so in public. As an historian she has been more widely read than Manning Clark (it would be interesting to know how many of the purchasers of Clark have been able to finish each volume); and she and Wendy Lowenstein have listened to the histories of more Australians than probably the rest of us put together. But she remains insignificant in the eyes of the theorists of oral memory and historical consciousness.

- Book 1 Title: Goodbye Girlie

- Book 1 Biblio: Viking, $29.95 hb

The trouble with Patsy is that she is unfashionable. First she takes great pleasure in close friendship and solidarity with other women and has deeply loved her mother and her sister. But she also has always liked men, and not the reformed sensitive New Age Guys either, but the men of the bush and the sea, including even the boozers and the bruisers. It started with her own father, a railway ganger who was unforgivably maimed by World War I, but who remained a gentleman who loved the women of his family beautifully all his life. To her horror Patsy Adam-Smith has found her life story rewritten by academics to readjust her father into the brute working-class fathers are expected to be. So she has been a lover of men, not all of them as a lover, but as a workmate or comrade, and she understands the ways working-men have dealt with frustration and tedium because she too needs freedom: it ‘is the sweetest thing and I ran headlong into it’ she begins her autobiography.

She married early and miserably, and when it became intolerable she took her adored children and walked out. She was a working-class girl who left school at fourteen, yet who wanted to support herself as a single mother while writing. She ended up going to sea as a radio operator (and extra deck hand) on small ships in Bass Strait and became the first woman to receive signed Articles in Australian waters.

She discovered sexual passion after a frozen marriage and she also discovered that she wanted to remain independent, and so when a six-year relationship fell apart, she went to sea again. When her lungs went into complete revolt against the Tasmanian cold, she knew she would die if she remained and so she went to the Kimberleys. There she joined a man minding cattle stations for absent owners and began her other life amidst the people of the outback: ever since she has returned to winter in the Kimberleys.

Patsy is also unfashionable because she comes from working-class respectability – puritanism born of necessity and pride. Her mother was always ‘a battler’:

It meant not to ‘get on’ but merely to survive, to hold her family together, feed and clothe them decently, gi.ve them dignity while avoiding the dogooders – those whose supposedly ‘good works’ were always repressing because of their firm belief in the social order of the rulers and the ruled.

But one of the cardinal rules of working-class life was that one should never get ‘above oneself’, because if you did, you could not survive. Patsy, however, was ‘a duchess’, so dubbed when in front of visitors she screamed ‘I’m not going to scrub floors’. This was not a refusal of family duty, it was all the awfulness of the future of poor rural girls:

‘I’m not going to scrub floors!’ There was no time for silence or shock. Mum had leapt up as if she expected this. ‘The Duchess, eh? Too big for your boots to scrub floors, eh?’ And all the while she shouted it I knew it was something else that contorted her face: she knew there was no other employment and there was no more schooling for me. I would have to go out as a slushy. Had we been alone it wouldn’t have boiled over like this, she may have discussed it, said it wasn’t real flash but what else was there? But now the lines were drawn. I screamed ‘I’m not going to scrub floors!’

She was always a ‘goer’: dancing, playing the piano, planning plays at school, writing screeds because writing was a hunger like food, reading whatever she could scrounge because there were no books at home. She is one of the most remarkable autodidacts we have had in this country, but she is not acknowledged as she should be because autodidacts are too often assumed to be male. She would be among the best-read Australians of her generation, but the self-developed intellectual life cuts little ice these days with the academy. Her historical writing is dismissed as ‘popular’ and ‘uncritical’, when in fact it is driven by a hunger for the ‘truth behind and within’ and yet at the same time is written amidst the people she is writing about. She has pioneered what you could call ‘participatory history’, and the companionship of the historians’ subjects quite changes the rules: suddenly the historian has to learn charity and respect and to understand from within.

Above all Patsy Adam-Smith is ruthless in the way writers need to be: obsessive, perfectionistic and sufficiently convinced that what they have to say is worth all the pain they inflict on both others and themselves. In the end she is one of Australia’s great story tellers, and the life she has led is quite as extraordinary as the many she has salvaged for posterity.

Comments powered by CComment