- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

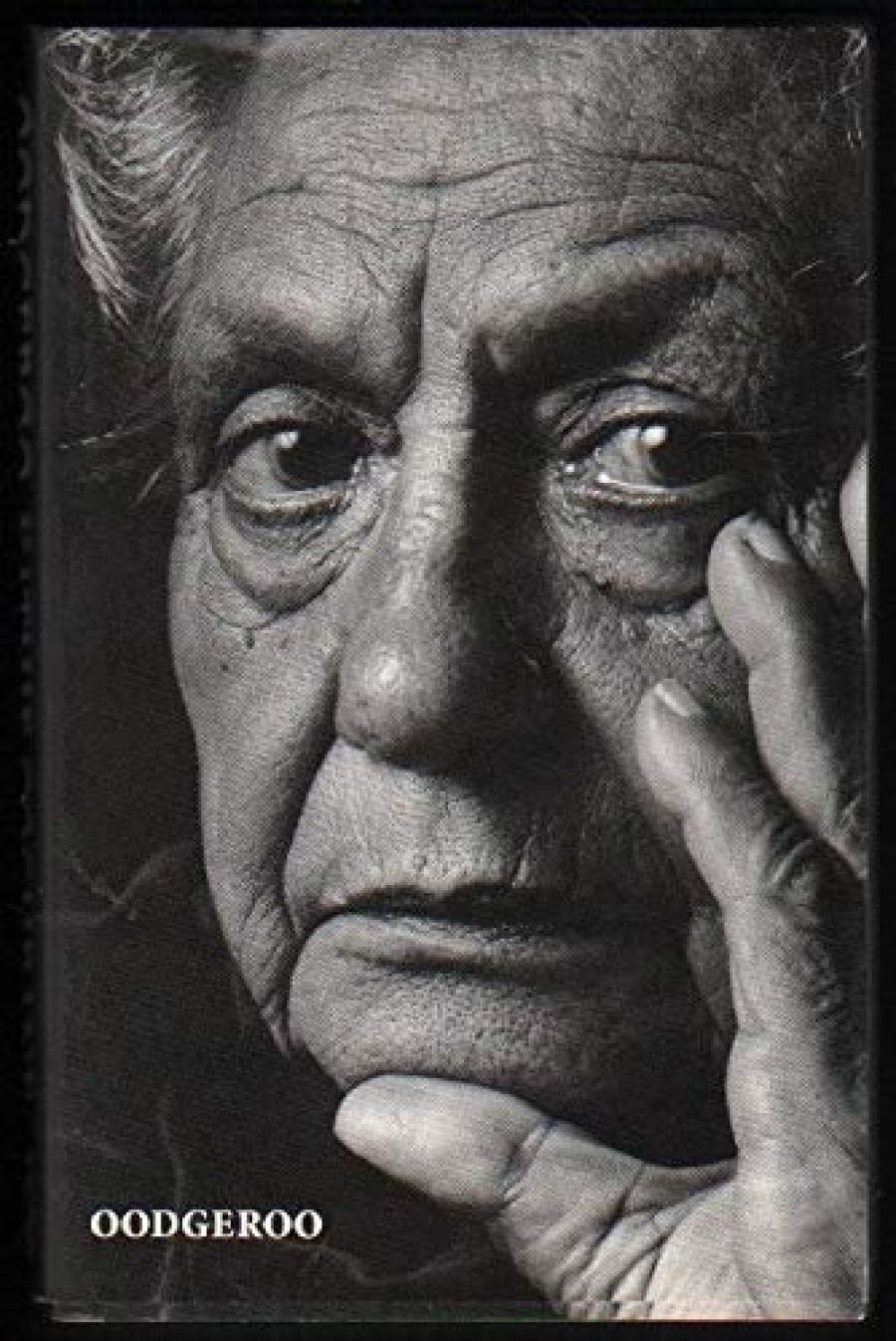

A striking black-and-white photograph on the front cover of Oodgeroo implacable and wise. And then the publisher’s blurb on the back cover

- Book 1 Title: Oodgeroo

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $16.95pb

Kathie Cochrane is not an Aboriginal but was authorised by Oodgeroo to fulfil the role of biographer. Her book is a testament to that long friendship and a sensitive portrayal of Oodgeroo, who she was friends with for thirty-five years. Cochrane first met Oodgeroo in 1958 when she and her husband were involved in the formation of an activist group for the improvement of the social situation of the Queensland Aboriginals and Torres Strait Islanders. The Cochranes asked Aboriginal people to become involved in the group and invariably found their invitations politely declined. The suggestion kept being made that they should see someone named Kath Walker (later Oodgeroo). Such was Oodgeroo’ s reputation in the Aboriginal community at that early stage.

Oodgeroo at the time was a single mother who had already served in the Australian Women’s Army Service. Like many Aboriginals she found that the Army with its emphasis on conformism and regimentation provided a space in which Aboriginal and White could meet without racism. Oodgeroo had also been involved with the Communist Party and while not comfortable with the comrades wanting to write her speeches for her, had sharpened her political skills under their guidance. She was already writing and was a member of a group called the Realist Writers. Oodgeroo’s involvement with Cochrane’s fledgling organisation led to the friendship that leads to this biography. As well as providing a narrative of Oodgeroo’s life Cochrane provides a personal history of these early attempts by socially concerned Whites to improve the lot of Aboriginals in Queensland.

As a writer Oodgeroo’s achievements are all the more remarkable in light of the difficult hand she began with. Leaving school at thirteen Oodgeroo became a domestic servant. A line of work that exposed Aboriginal women to the depredations of White men and which could erode the self-esteem and pride which are features of Oodgeroo’s poetry. Judith Wright contributes a sensitive appreciation of Oodgeroo’s poetry and the context in which it was written. Wright, who was a reader for Jacaranda Press when Oodgeroo’s manuscript for We Are Going first arrived, writes:

Was it poetry? It could be set against the general run of largely boring and cliché-ridden verse that thudded on to publisher’s desks every day and was promptly sent back; in Queensland in those days there was a lot of it, as I had cause to know, not only as a reader for Jacaranda but in past days for Meanjin too. Ideas were few; fire and urgency were nearly non-existent. This stuff was alive.

Cochrane’s biography is the biography of a friend and in some ways this is its limitation. It can be difficult reconciling affection with analysis and criticism and in view of the sensitive issue of White biographies of Aboriginals may be best avoided.

At the end of Oodgeroo’s life, her stature in the Australian community was probably the highest it had ever been. Her poetry was being read seriously; and as feminist; earth-mother; environmentalist and elder she was able to embody many of Australian society’s popular concerns. Part of this remaking of Oodgeroo happened after her retreat to Stradbroke Island in 1971 when it seemed she had been made redundant by a new era of Aboriginal affairs bureaucracy and activism. A more explicit examination of the processes and individuals who were part of this re-making of Oodgeroo would have been valuable.

The book presents in a transparent manner Oodgeroo’s relations with Whites. Oodgeroo’s life, at least from young adulthood, was characterised by diverse and reciprocal relationships with Whites. An accomplished sportswoman who represented Queensland in cricko; photographs in the book show her being chaired off the field by White team mates. She formed friendships with Whites while in the army. As well as her involvement with Whites in political and literary circles Oodgeroo also had close relations with the establishment Cilento family. Sir Raphael Cilento was a co-editor of the Queensland Centenary publication Triumph in the Tropics. In the words of Ross Fitzgerald this publication, ‘contained racist attitudes unequalled almost anywhere in the world at that time’. These complexities don’t sit easily with Oodgeroo’s simplistic definitions of assimilation or descriptions of Aboriginals who achieve in the tertiary system as Jackys and Marys. But I would suggest that of deeper concern is with the equanimity which some Whites accept such simplifications.

This biography is a depiction of a ‘modernist’ era of White/Aboriginal relations that began in the 1950s and continues into the present. One of the dispositions that characterises this period is the attempted displacement of White guilt, homelessness or lack of national identity through the mediation of representative Aboriginals and narrow readings of representative Aboriginal texts. The texts and the ‘representatives’ (who can be radical or conciliatory) play important roles in the psychic economy of White individuals and White society. Judith Wright’s poem ‘Two Dreamtimes’ is a revealing example of this drive to resolve guilt through a representative individual, and a recognition of the impossibility of its fulfilment. The two women, two poets, meeting as sisters, each a shadow to the other:

My shadow sister, I sing to you from my place with my righteous km, to where you stand with Koori dead ‘Trust none – not even poets.’

Comments powered by CComment