- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Virtuoso display

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

One of the defining features of recent years in Australian ‘literature’ (as I suppose we must call it), in tandem with a perceived growth in the quantity of fiction and poetry by women, titles reflecting the ethnic diversity of origin in more and more writers, and a growth industry in Aboriginal studies, has been the remarkable increase in sophistication of approach to biography. Perhaps more specifically, cultural biography.

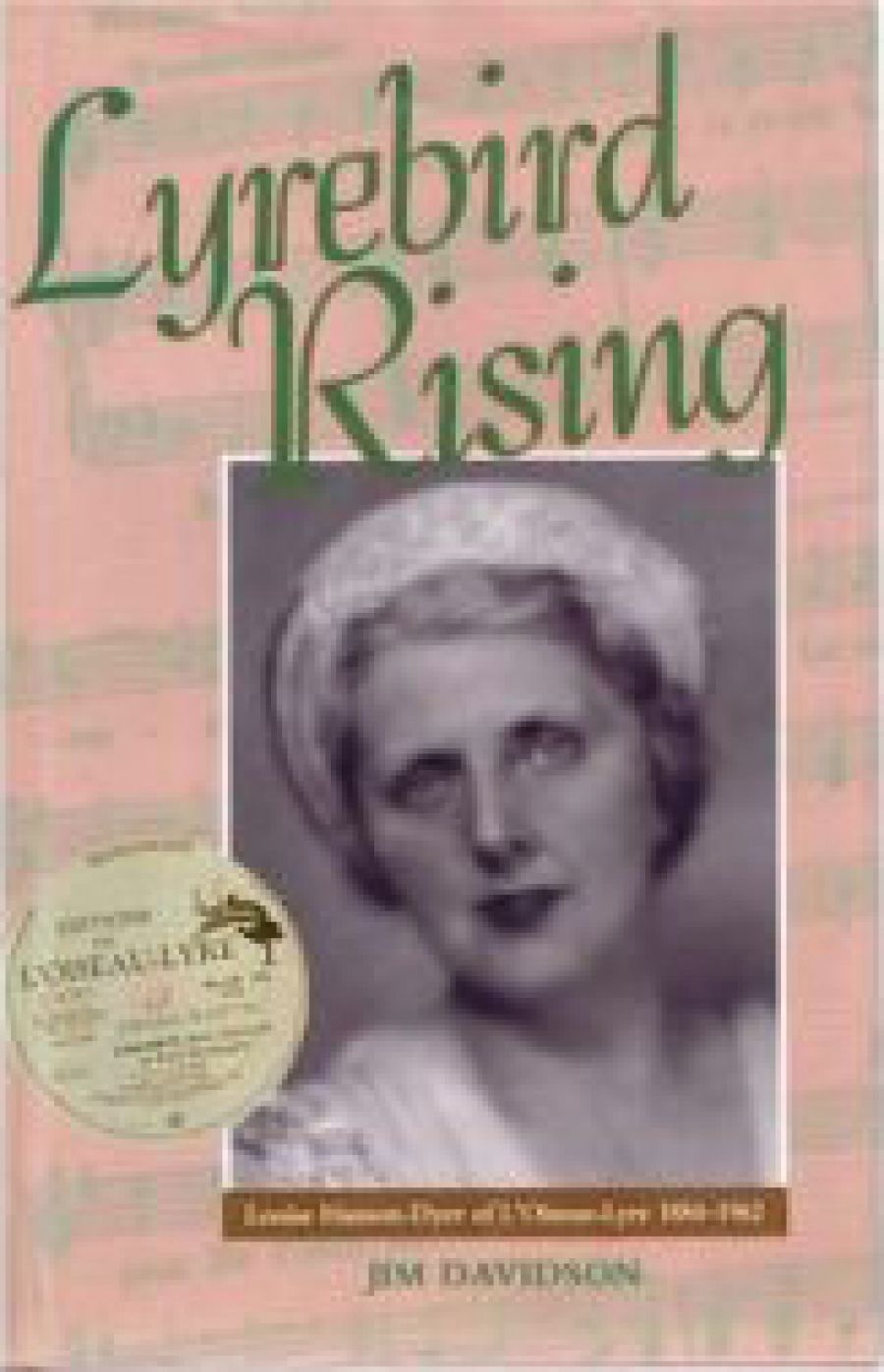

- Book 1 Title: Lyrebird Rising

- Book 1 Subtitle: Louise Hanson-Dyer of l’Oiseau-Lyre, 1884–1962

- Book 1 Biblio: Melbourne University Publishing, $49.95 hb

Books on the lives of political and socially influential figures proliferate, some of them establishing new records in sales. Others, such as Tom Boland’s on the Brisbane Catholic Archbishop, James Duhig (1986), carved out large claims for a broad contextualisation of figures otherwise thought of as marginal. Perhaps that, too, was the successful outcome of Brian Matthews’s self-conscious book on Louisa Lawson, Louisa (1987). What is intriguing is that in the burgeoning field of Australian biography literary and arts figures have moved increaseingly to the fore – in sales, as well as in critical appreciation.

David Marr’s Patrick White is the obvious watershed, though on a more modest plane such a book as Garry Kinnane’s George Johnston: A biography (1986) was quickly reprinted within its first year of publication, and Brenda Niall’s Martin Boyd: A life (1988) came out in reprint and in paperback almost immediately. To this one can add Geoffrey Dutton’s life of Kenneth Slessor and perhaps the curious doubling-up of books on Frederic Manning, by Jonathan Marwil in 1988 and Verna Coleman in 1990. The Last Exquisite indeed!

David Marr’s biography has been succeeded by Hazel Rowley’s on Christina Stead (1993), with Mary Lord’s more autobiographically titled book on Hal Porter deflecting the genre into a different sort of encounter.

Jim Davidson’s book on Louise Hanson-Dyer is something of a virtuoso display. It expands the line of historical-social treatment of its subject, rather than the personal or anecdotal – though it is filled with wellplaced anecdotes.

Like Marr and Rowley, Davidson offers his best insights in studying the development, as well as the life, of an Australian who was inescapably bound up with a specific family and regional origin but who found crucial energies through expatriatism. All three subjects – Patrick White, Christina Stead and Louise Hanson-Dyer – in various degrees developed as much through their Australianness as by reaction to it. Patrick White, finally and savagely, embraced it with amorous loathing; Christina Stead transmuted it into one of her two undoubted masterpieces, The Man Who Loved Children, and Louise Hanson-Dyer translated the image of a lyre-bird from the Dandenongs into a motif of rarefied but potent international affirmation.

With these three biographies we discern the way discourse on this particular stage of cultural review is being clarified. All treat the ‘problem’ of post-colonial development – the true preoccupation of the 1990s – through examination of early to mid twentiethcentury exemplars. Undoubtedly the fascination of Rowley’s study is the detailed appraisal of Stead’s overseas years, just as Marr’s book had as its central revelation an elucidation of the period of White’s career that led to the possibly surprising decision to return to Australia in the early 1950s.

Davidson has chosen a figure more exotic, and more nebulous, as the basis of his rigorous and sometimes rarefied study. Although it is announced that the book has its basis in a PhD thesis, this is only apparent in the thoroughness of the appendices and the fine detail of its account, in the later chapters, of Louise Hanson-Dyer’s largest claim to fame, the growth of her long-playing record imprint, Editions de l’Oiseau-Lyre. And as is rightly pointed out, this is the first study of the behind-scenes activity in one of the century’s cultural and economic growth areas. In a deft finale, Davidson charts the ripple effect across cultures and between cultures provided by the long-playing record and the musics – old and new, near and far – disseminated through their technologies.

The book is thoroughgoing in its research. It is also witty, sly, and poised with a historian’s perspective upon any number of seemingly quotidian incidents. The ‘life’ is both a personal unveiling of the subject, and a positioning of her in a way that I think does not do violence to her own historical placement. The world of the 1950s can seem impossibly remote to us now; the world of the 1930s is something we think we have set in its frame. By using the image, or token, of music Davidson shocks us back into a refreshing review of what happened, to whom it happened, and how otherwise it was to what we take for granted now.

The early chapters, describing Louise’s family and a Melbourne at the peak of its early boom period, are tidily done – though at times I had the feeling that the author was snipping his sentences too tightly, wanting to pare as if he were doing a word count.

Once we get Louise and her education, the interpretation of colonial and post-federation life is given point through musical (and sometimes literary) examples. The presence of a High German musical culture, for instance, links us into a pervasive influence that was to be suddenly jettisoned with destructive ferocity in 1914. In view of Louise’s later French connections (and her vehement rejection of things German) this is telling; but in a wider sense it also underlies a genuine multicultural prominence that perhaps only Brisbane rivalled at that time. Adelaide valued its German goldsmiths and craftsmen, and its German farmers, but Brisbane possessed in Eugen Hirschfeld a prominent doctor, agricultural scientist and state politician, who was also a patron of the arts.

Those who had heard of Louise Hanson-Dyer before this book may have been interested because of the long-playing record label she pioneered. But she was in her forties before she left Australia for good. Davidson’s account of her first mature years as a wealthy Melbourne matron and arts patron directs us to contextualise many of the incidents in that early career; for instance, this passage on the neglected Australian composer Margaret Sutherland:

Meanwhile Arnold Bax, Sutherland’s erstwhile teacher, divested himself of the opinion that ‘This is the best work I know by a woman’. Sutherland’s husband, a psychiatrist, thought that as a woman she was mad to be seized by the notion of being a composer, and had proffered himself and domesticity as the remedy.

The book is full of such felicitous taunts.

The Paris years: if in a sense these become the core of the book, they are also the biggest challenge. One of the subterranean delights a modem reader has in these biographies with their representation and interpretation of the lives of those who left Australia is the roll-call of the great and famous – the overseas great and famous – who flit through the pages. It is also the reason books on the London Bloomsbury group continue to sell and to fascinate. Almost forgotten names are revived and shoved back into a fresh context. There are enough of them to tap an instant response, and enough of the almost-forgotten to invite the reader to dip back into the era and re-tip the flavour. With the Bloomsbury group it is not the main players, but lesser figures such as Angelica and David Garnett who have benefited. In the Patrick White biography, someone such as Roy De Maistre achieves new prominence, and with Christina Stead we revisit all those left-wing writers of the 1930s in the States.

In Lyrebird Rising there are brief but fascinating glimpses of the ambitious Australian making her way and even establishing a successful salon with the influential composers of ‘Les six’, catches like Joyce and Pound, and having her portrait done by Max Ernst. The USA expatriates, much written about elsewhere, inhabit a Left Bank of peculiar isolation from surrounding French culture. Louise embraced it, even if with a hopeless strine accent and a ton of push.

The narrative engrosses, and the cultural placement is always evoked with precision, and that sly wit. More tellingly, Louise’s discovery and publication of early European music is told with sufficient grace and authority to hold the reader. What began as a social study of forty years of Melbourne life (climaxing in the petty rivalries about establishing a Symphony orchestra, a narrative that drips with import) then translates into a parallel account of coteries and rivalries in 1930s Paris. The perspective is reversed: here is a culture grappling with fragmentation and decay, rather than with growth and ambition.

The import of Louise’s initial L’Oiseau-Lyre music publications makes their stature clear, but not too heavily underlined. Accounts of the mechanics of production are enough to shrivel the less resilient. Louise was the sort of Australian-hardy we do like to claim as our own.

Her first husband was twenty-five years older and wealthy. Her second husband was nearly twenty-five years younger. One wonders how many women could have handled such extraordinary disparities, pursue a wilful career, and retain absolute loyalty. The answer has to be personal charisma. If one retains a gentle sympathy at the old man’s folly in marrying her, one also is almost convinced that the second marriage was something more than mother-surrogate bargaining; we have been gently led by the author in this.

Perhaps a final snippet from the book will serve to give something of Davidson’s flavour, and his placement of material. This occurs when Louise is quite old, failing in health, and buffeted by technological change and the mechanics of keeping up production and schedules:

Louise thought nothing of sitting at recording sessions with a stop-watch at hand, making sure that she got the full twenty useable minutes that unions permitted from each recording session. She would also gently assert her presence to all and sundry at those sessions by pouring the tea; then, at the conclusion, produce a big white handbag, from which she paid musicians their fees in large £5 notes ... But even the wackiest stories about her often had a surprising point. When Raymond Ware was visiting Louise and Jeff in Paris, and still slightly feverish from the ‘flu, she nevertheless insisted that he get into a cab and come over ... he was surprised to be told that he should drink some champagne from a slipper. ‘You need to do this twice’, she said, producing the footwear. ‘Use the heel, and hold your throat’ ... next morning he was able to report that he felt better.

Comments powered by CComment