- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

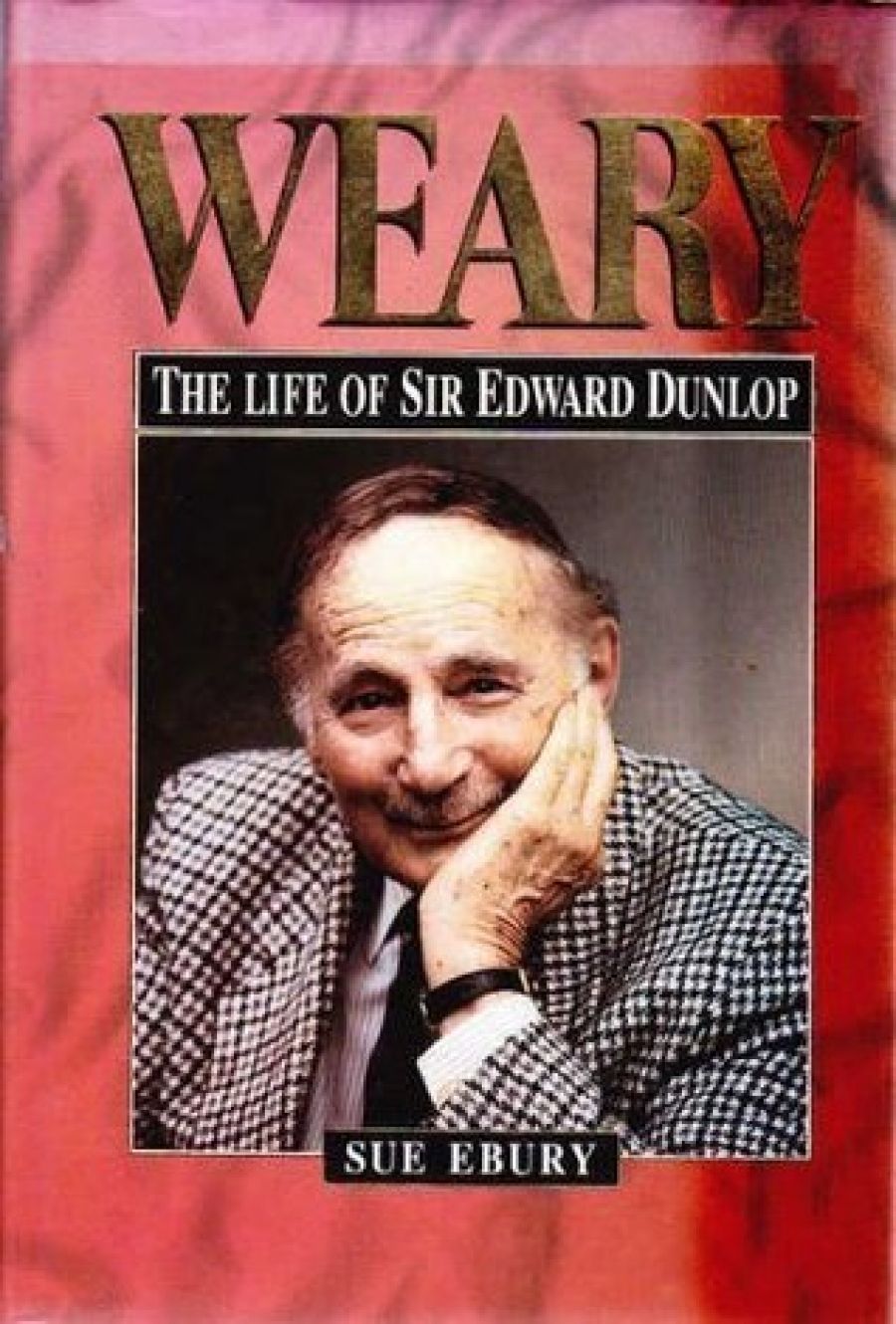

Over 35,000 copies of the hardback edition of Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop’s war diaries had been sold before they were reissued in paperback. Now Sue Ebury, who edited those diaries for publication, has written an accompanying ‘Life’. An impish picture of the older Weary in a sportscoat looking rather smaller than he really was grins beneath his name written in gold on a red silk background. In the paper edition it will surely be embossed.

- Book 1 Title: Weary

- Book 1 Subtitle: The Life of Sir Edward Dunlop

- Book 1 Biblio: Penguin, $45 hb

Two-thirds of the book is devoted to the story of Weary’s life before he arrived in Java in 1942 and after he returned from Thailand in 1946. Given the reputation of this ‘farm boy, scholar, sportsman, surgeon, soldier, diplomat, statesman’, it is unlikely readers will need to be told who he is. Those who knew and loved him when he was alive will undoubtedly read every detail of his boyhood experience, academic career and sporting triumphs with pleasure. Names seem to be quite significant, a clue perhaps to the character of the man.

Christened Ernest Edward, known as Ernie or Em in his Benalla boyhood, he accepted Weary for popular consumption but preferred the more elegant Edward for professional purposes. If you are interested in the initiation ceremonies by which he became an ‘Ormond man’, or how many times and in what manner he broke his nose playing football, every detail is here. Indeed, it becomes very difficult to decide what in the dense narrative of his early life is really important for understanding how he became the man he did.

The story gains momentum where it is based on the war diaries, but becomes anecdotal again after the war, when he returned to surgery in Melbourne. A man of action with a temperament that enabled him to press on when many others would be dismayed by the odds or the likelihood of defeat, he practised surgery also in an ‘up and at ’em’ manner, tackling cases on which no other surgeon would risk his reputation, and worked constantly as an advocate for ex-POWs. Through his friendship with Richard and Maie Casey he became involved with the improvement of medicine in India and South-East Asia, and in 1969 returned briefly to the field with a medical team in Vietnam.

A younger generation, no longer in touch with the memories of the Second World War, may wonder why they should read this book at all and what all the fuss has been about. For much of the time its atmosphere reeks of masculinity, the single-sex school, the football changing rooms, the camaraderie of the operating theatre, and of course war which is so often described in sporting terms. We have moved away from the kind of sex-segregated society in which men like Weary Dunlop revelled. (He took female help for granted, expected it to be totally efficient and completely sexless – the nurse utterly in the Nightingale tradition.)

‘He gave his country a vision of sacrifice, compassion and service’, the author concludes. This may be true, though would any of it have been possible, or would he have achieved the same recognition without the death and suffering of thousands of lesser men in war? Unnatural conditions produce unusual leaders, but how well do they serve as ideals for different times, other circumstances? Without the war, what kind of man would Weary Dunlop have become – an ageing ex-hearty, a crusty conservative, driven to ever more heroic surgery? Ghosting through this story of action, mateship, aggressive high spirits and sheer bloody-mindedness, is a wife and family whose lives were a tragic counterpoint to his. In a way it would be better if, as in more old-fashioned biographies of such men, we knew nothing of Lady Dunlop. She is an embarrassment, not relevant to the main action. Weary was a man’s man and many readers would probably feel more comfortable if this were a book entirely about men’s business. And yet, reading now the accounts of his work in Thailand, it is striking how much of it was really the kind of work performed daily by most women in their capacity as housekeepers and mothers – maintaining hygiene and order, monitoring health, juggling a limited budget to ensure a proper diet and adequate clothing. Housekeeping in the POW camps and hospitals of Thailand was heroic work. Weary Dunlop inspired and was revered by his men in the same way perhaps as some mothers inspire and are revered by their children. This may be the essential strength of men like Dunlop, that their ‘feminine’ side can be expressed in strong and creative ways. Like Jesus Christ – with whom he was sometimes identified on the Burma railway – Dunlop had his gentle side. Teasing such thoughts. from this account is not easy, though they lurk behind the relationship between author and subject, while the book itself is an open window for anyone trying to understand the complicated nature of leadership or masculinity in Australian society.

Comments powered by CComment