- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

What do we do, where do we go to get beyond the routines of the self and the paradoxical alienation it produces in both ourselves and in others? Is it possible to break down the shell of separation and deal with others from a perspective that is neither ‘self- or need-observed’? These are the questions that occupy Bruce Beaver in many of the poems in this collection, and one that he traces through an engaging variety of forms and themes.

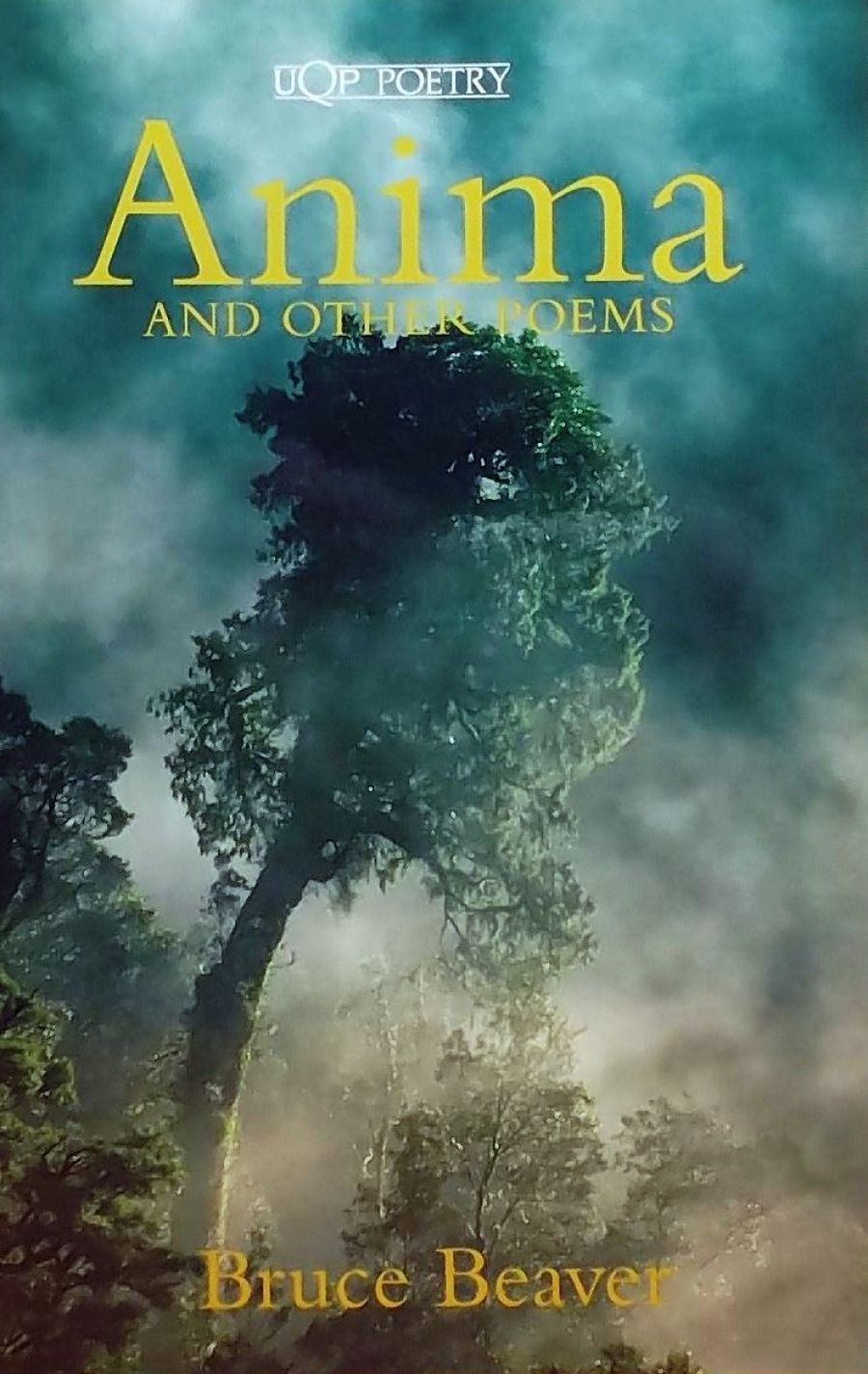

- Book 1 Title: Anima and Other Poems

- Book 1 Biblio: UQP, $14.95 pb

There are both lyrical and philosophical dimensions to the answer he provides. In ‘The Lovers’ it is the ‘leaf of love’ which splits ‘the adamant of selfhood’. In the more densely speculative ‘Out of the Race’, he puns on the multiple meanings of the word ‘race’ to suggest that the problem resides in a fixed sense of who we are and the competitiveness we bring to every interaction (‘to beat time and each other at the last/ post, winning another’s loss and leaving/the rest for dead, or worse ...’). For want of a better word, he describes the condition of’ calm passed all believing’ as a form of love.

The long title poem, ‘Anima’, is about this very same love in all its bewildering ferocity. Written in effortless blank verse, it is both a poignant depiction of consuming passion between two unsuspecting people and a ruthless confession of weakness and betrayal. The love described here is at first predominantly erotic, but as the narrative develops and the relationship evolves, there is a growing sense of mutual respect.

I found Beaver’s evocation of an intimacy that accepts the sexual and yet exceeds the physicality of immature passion (‘a knot of limbs/an extended mini-orgy’) very moving. A voiding the pitfalls of sentimentality and embarrassment, he manages to evoke in words ‘that shared immediacy of always’. While there has been much discussion recently about the writing of eros, ‘Anima’ reminds us that it is perhaps this intimate togetherness that is harder still to capture.

The three poems of ‘Night Watch’ evoke an absence of intimacy in the view of an inhuman city skyline. Lying awake in a hospital ward in the early hours past midnight, the poet is amazed to see a businessman dictating to his secretary in a nearby office building. Struck by the oddness of their activity, Beaver meditates on the comedy of self and the drabness of the mundane. His musing delights in the incongruous: a banana-shaped balloon, businessman as devil incarnate, Sibelius’s celluloid collars.

Yet despite this encounter with the forces of darkness, it is the promise of another day that imbues the poetry with an understated optimism. I can imagine some readers finding Beaver’s work old-fashioned or even deliberately archaic in its use of language, but while his register is often elevated, there is nothing overblown or impossibly obscure in his choice of words. His facility with demanding forms is made clear in the six sonnets ‘From Norfolk Island’ and the nine-line stanzas of ‘A Nest of Nonnets’, a tribute to Gwen Harwood. There are also two examples of the infernal sestina, a form with all the charm of a cryptic crossword.

Although Beaver manages them admirably, it is interesting to note that it is here that he aband9ns personal themes for historical and mythological concerns. To its credit, ‘The Amazons’ attacks the ‘sexist blather’ of Robert Bly’s reactionary Iron John, but I wonder whether readers will have as much fun decoding Beaver’s satire (involving Achilles, Thersites and Penthesilea) as the poet had in writing it. While I admire the formal perfection with a rather abstract appreciation, my predilection is for the singing lines and richly detailed narrative of poems such as ‘The Dispensation’ with its feline hero George:

From the sill

onto the desk, into my something like

serenity you once again erupted

like lava recollected in tranquility,

flowed over all my best and worst

intentions

of work and caused me to make my first

mistake:

a saucerful of milk reluctantly relayed

to ever thirsting and rebarbative

tongue.

Equally resonant are the three poems of ‘Pellucid Days’, each line a lapping wave of sound across the page. Beaver is here unabashed in his word-and-water worship and fashions a liquid language fit to match the rhythms of the sea. He is, however, sensitive to the need for contrast, and provides a couple of memory-driven prose poems (‘The Lovers’ and ‘Earth and Fem-Softened Rock-Face’) which give scope to a more restrained lyric voice.

In the second of these, he juxtaposes landscapes of memory and imagination and leaves us with a wistful reminder of how limited we can be in our helpless selfishness:

We set everything in a landscape: our real and imagined encounters with ourselves and others. We inhabit our minds and rarely learn to get out there beyond the backyard, over the tall fences or, better still, up the steep track to the left and on, overlooking the yard, the house, the harbour, the world, past all that holds us captive in ourselves.

Comments powered by CComment