- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: White drifts towards black and becomes technicolour grey

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

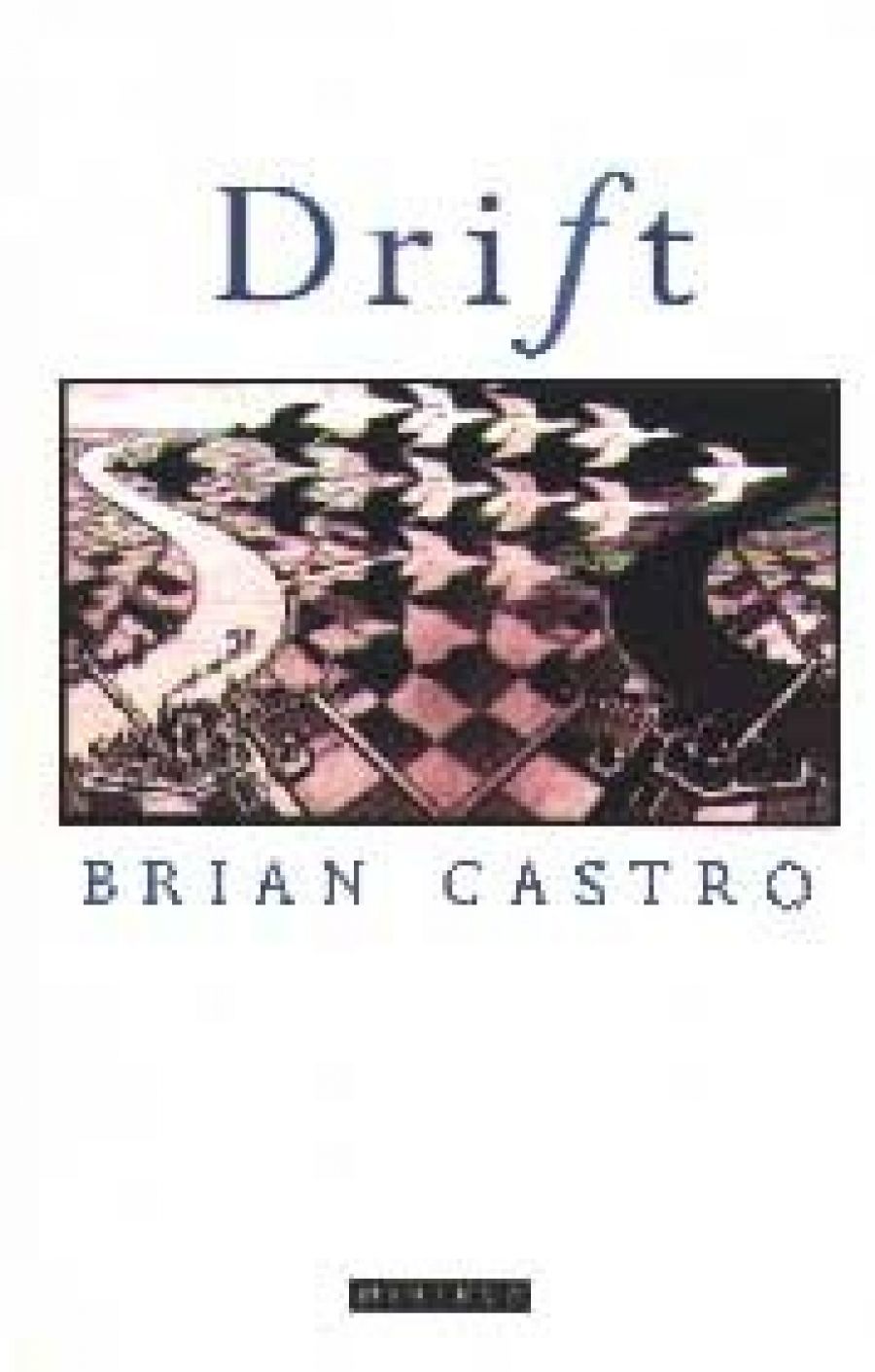

You can’t help wondering which came first for Brian Castro – the theme/structure of his new novel or the M. C. Escher woodcut reproduced on its cover. It doesn’t seem possible that such an organic match should be fortuitous, although one of Escher’s soubriquets is ‘the poet of the impossible’, and among writers Castro is a prime candidate to share the title. Now that it has been drawn to my attention it is also of course obvious that the seaside hotel in After China was built to Escher specifications.

- Book 1 Title: Drift

- Book 1 Biblio: WHA, $24.95hb

The print – entitled Day and Night, though that would be among the least of the dichotomies Castro draws from it – shows a pair of waterside towns, one dark, one light, joined by a patchwork rural landscape which metamorphoses – drifts – into the shapes of birds: complementary black and white geese shapes, the black flying west into the light, the white heading east against the dark, the eye of the beholder caught now by one, now by the other, so that as the angle of focus changes wings beat and the birds stream in opposite directions across the page.

It is a brilliant trick, a triumphant sleight of hand/eye that Castro reproduces and builds on magnificently, infuriatingly, in the novel. Paradoxically, perhaps, if you like things in black and white – fixed premises, unequivocal answers – this is not the book for you. As on its cover, so within: everything moves and shifts and comes round again in subtly altered focus; trying finally to pin down meaning can lead to madness.

Castro bases his novel on the fact of an important but little-known experimental novelist, London-born Bryan Stanley Johnson, and proceeds to make a fiction of him, while pointing out in the Preface that Johnson’s own unpopularity was a function of his insistence on subverting fiction with fact. Castro, in the guise of his character (Johnson’s character) the Tasmanian Thomas McGann, ironically rechristens Johnson ‘Byron Shelley’, and sets out to complete his projected Matrix trilogy on the grounds that the first volume – the only one Johnson (Bryan Stanley fact or Byron Shelley fiction) had actually finished when he suicided in 1973) – contained a single unmistakable reference to Tasmania, and that the writer invited his readers to finish the other two volumes for themselves (a notion which is casually and typically subverted further down the track).

Given that the Preface is assigned to the character ThomasMcGann, what credence can the reader give anyway to these so-called facts? The dust jacket – another traditional, if traditionally unreliable, repository of facts about the fiction to follow – gives B. S. a different character’s date of death and ascribes to his pen an unlikely selection of Australiana. See how Escher-esquely convoluted, how Mobian we are already, and we’re only up to the Preface! The discovery at this stage of an entry in the current Oxford Companion to English Literature for B(ryan) S(tanley William) Johnson (1933-1973), experimental novelist, was for this reader the ultimate in dislocation: that I found myself doubting the Oxford Companion rather than the novel is an odd but effective measure of the power of Castro’s invention.

It is from Tasmania that Johnson, now penning his own obituary/life history, starts to receive fanmail from Emma McGann, black twin of the albino Aboriginal Thomas, descendants both of Thomas ‘Sperm’ McGann, who was transported in 1799 for baring his fifteen-year-old bum at mad King George. McGann survives (in two different versions) indentured servitude and unrequited love and escapes both to become a whaler. Stark and evocative descriptions of an elemental nineteenth-century existence on Tasmania’s rugged edges interweave Johnson’s accounts of life and love in Hammersmith and South Wales; subjugation and unrestrained slaughter of humans, whales, seals, make a bloody physical counterpoint to the writer’s predominantly urban introspection – yet not without some sense of camaraderie, even of love: Castro’s great strength, like Escher’s, lies in his shaping of the shades between the illusory simplicity of black and white.

Dichotomies abound, and it as Castro’s delight to explore, exploit, explode their duality, whether they be black/white, male/female, north/ south, writer /reader, fact/fiction, truth/lies, life/ death or the contradictory/complementary meanings of his one-word title. Castro defines his polarities and then plays in the grey area between them. Very little, in the long run, is as it seems: a bizarre but effective exercise in empathy means that Johnson’s white is soon black, particularly next to the albino black McGann; McGanns of two generations, and Johnson on his self-delusive search for truth and justice in Tasmania, die the deaths of Saturday cinema matinee heroes, constantly resurrected against all odds to fight again another day; who is to say that the already disputed death of 1973 (1993?) will prove any more permanent?

This is a funny, fascinating, fabulous book – a quirky celebration of unsung genius, an earthy intellectual comedy, a swag of vividly picaresque adventures, a tragedy of licence and waste, rape and slaughter made arrestingly, challengingly real. In a dazzlingly pyrotechnic display of often irreverent erudition Castro has borrowed from everywhere: there is scarcely a phrase which doesn’t call up echoes across the novel itself and into literature, history, Christianity, so that a relatively small book explodes into a vast network of shared reference and experience. Much of this reference is necessarily grounded in the English-speaking West, but it may not be far-fetched to suggest that the novel in its entirety (as distinct from its variously entertaining and thought-provoking parts) takes its significance from the East and represents a Zen-like search for enlightenment which attempts to transcend dualism, to step outside of logic and to divorce truth from the words which so equivocally convey it.

Comments powered by CComment