- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Interview

- Review Article: Yes

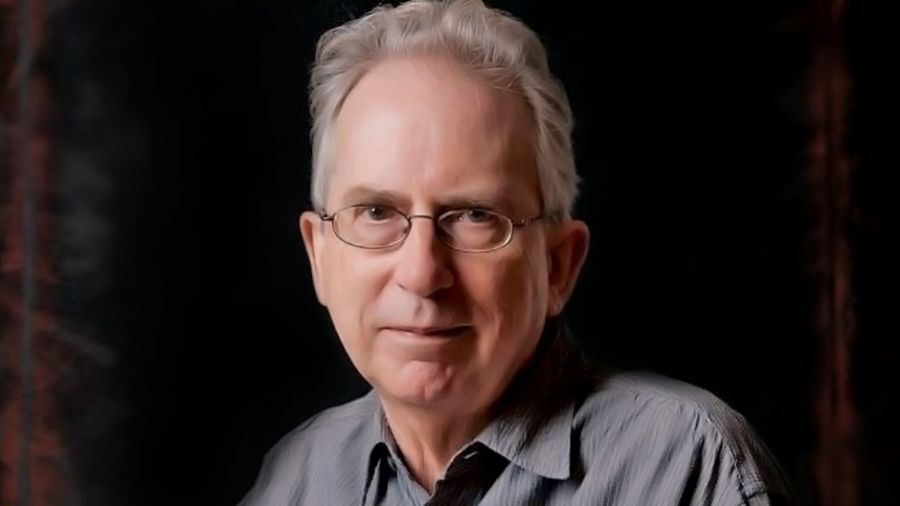

- Article Title: An Interview with Peter Carey by Robert Dessaix

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The first draft didn’t have Tristan, this deformed little character. Then I was reading to the kids, Beauty and the Beast. It was very beautifully written, terribly moving – and they were moved. I read it to them many times, thinking it would be interesting to look at that. Then, round about this time, I was walking along the street and glimpsed a terribly deformed young man in a wheelchair. I couldn’t bear to look at him yet I carried with me afterwards a vision, this bright, bright intelligence and this weird twisted-up face. It was quite moving and, having flinched from it, as from a fire or being cut, I began to make myself think about what was in there. That really goes back again to the very beginning of my work, the short stories. In the very beginning I was affected by Faulkner and As I Lay Dying because Faulkner was giving rich, interior worlds to people who you might otherwise pass by. That’s been a continual thing in my work, perhaps.

- Article Hero Image (920px wide):

RD: Yes, there’s a quasi-religious thing still there, isn’t there?

PC: Yes, absolutely. And so my characters were going to arrive in this place and be mugged or something similar and begin to live inside the mouse suit. My character was going to become immensely powerful in this society and, in fact, act out in more detail, some of the things that are suggested at the very end of the novel, where Tristan has his affair with the millionairess.

Anyway, that’s where I started. The first draft didn’t have Tristan, this deformed little character. Then I was reading to the kids, Beauty and the Beast. It was very beautifully written, terribly moving – and they were moved. I read it to them many times, thinking it would be interesting to look at that. Then, round about this time, I was walking along the street and glimpsed a terribly deformed young man in a wheelchair. I couldn’t bear to look at him yet I carried with me afterwards a vision, this bright, bright intelligence and this weird twisted-up face. It was quite moving and, having flinched from it, as from a fire or being cut, I began to make myself think about what was in there. That really goes back again to the very beginning of my work, the short stories. In the very beginning I was affected by Faulkner and As I Lay Dying because Faulkner was giving rich, interior worlds to people who you might otherwise pass by. That’s been a continual thing in my work, perhaps.

So I started to think about what was inside this person, and I thought ‘there’s a person who has a damned good reason to be in a mouse suit.’ So the opportunistic storyteller looking for a way to make things fit together, looks at that. And then I thought ‘it’s powerful, it’s interesting’ and there again it’s like a site of enquiry. Can I live with that? Am I interested to explore those things for a year or two? I was wary of the potential for writing about a monster being so off-putting to readers that they wouldn’t want to read about it.

RD: I’m interested in this question of beauty, because not only in this book, but in other works as well, certain characters have a hunger. Beauty always seems to be connected with hunger. Someone hungers for it and can’t ever really have it. It’s wonderful in this book the way this deformed child’s mother and father are so beautiful and the narrator keeps telling us how beautiful they are. Even years and years later, when they shouldn’t be quite so beautiful, their skin is burnished and their hair is shining. Tristan, all through his life, experiences an agonising hunger – how do you get what you hunger for? Art can’t really, despite what he is told early in the book, transform ugliness into beauty. Look at Benny in The Tax Inspector: he wanted to turn himself into something that erotically conformed to a fantasy, but in this book poor Tristan is simply left hungry.

PC: Tristan does imagine he’s going to transform himself, through art and through the theatre. There’s the line from Stanislavski that somebody performing appropriately, properly, even a deformed person, will appear beautiful, and Tristan latches on to that, as I latched on to it when I found it in Stanislavski.

RD: Is the power that you hunger for, is it the love that beauty brings with it?

PC: Beauty is, by definition, a highly attractive, desirable thing and I think we all respond to it. The thing about Tristan is of course that it isn’t going to be there for him.

RD: For people in these ex-colonies – still to some extent economic and political colonies – the basic attraction of Voorstand is glamour and a kind of beauty. It leaves very little else to offer. Do you think this is the main link between ex-colonies and the old imperial powers? A glamour, a beauty of a kind? An aristocracy?

PC: I’m not sure that my book addresses this, but I think because of the power of the culture, whether popular or high, that comes from these places, the colonies really grow up believing the real world is elsewhere. The periphery believes that the real world is at the centre, which of course is ludicrous, because ninety per cent of the world is on the periphery. And I think that the hunger that Eficans have for Voorstand is that hunger of the historically dispossessed or transplanted for what they feel is the real world.

RD: But the point about Voorstand in relation to Efica (and whether you care to think in terms of America and Australia, or Holland and South Africa, it doesn’t really matter), is that it’s got nothing to offer except simulacra, and things that don’t actually satisfy. I mean, the essence of its culture has to keep being (as it seems to in this novel) never quite satisfying hunger.

PC: So it’s an entertainment culture. What Voorstand is, in the book, is an addictive, glamorous entertainment, really of no profound worth at all, but yet oddly growing out of something that was original, something of real worth.

RD: But what is of worth? The question arises: what matters in a culture?

PC: Well, growing out of some principle then. In this case, you see this perhaps not very attractive, but still principled, Protestant sect – so serious about all living things that they believe that sparrows and mice have souls, and when they paint the crucifixion there are mice and sparrows. When I wrote about that I imagined rather anthropomorphic mice and sparrows there, who are vegetarians, and whose whole very principled beginnings end up in this tawdry circus. Of course that has some resonance that one can struggle with, in the reality of the United States. And although I began at that point, I really spent two years trying to invent these countries, and it becomes very unsatisfactory for me. I sometimes have to talk about the United States in order to talk about the book. And it becomes very unsatisfactory too, because I see in so many ways Voorstand isn’t like the United States.

RD: We on the periphery, though, in a kind of wash-up of colonialism, we do have to ask ourselves (and in your earlier books you keep asking) what you do with a culture. Do you try, on the periphery, to reinvent a culture? Do you try to take what you have been given from the imperial centre and transform it? Do you try to start from scratch, with indigenous roots and do something with them? In this book, one of the things that worried me was that Tristan has to get inside the Bruder Mouse suit and play their game. This is profoundly depressing. Do we have to keep playing their game? Are we always going to be just a flea circus, as somebody says?

PC: Tristan, finally, is not playing their game. The whole climax of the novel indeed is indeed what you’re saying: he’s playing their game. He’s inside the suit, he’s powerful, he’s articulate. For the first time in his life he’s actually desirable, but his true self is totally unacceptable to them. I think it’s a period of his life, a chapter or a period of Tristan’s unusual life.

RD: But that is the agony of many Australian cultural activists. That is, that you don’t know whether you’re supposed to go there and be a second-rate ‘one of them’ – writers want to be published in New York, they want to be published in London – or whether you should stay home and invent an identity for yourself at home.

PC: The truth is, we can’t be one of them, and I believe that the minute we try to be one of them we’re lost anyway. It’s a dumb move on every front. Betrayal might be too heavy a word, but a betrayal of your own culture, which seems to me an important thing. But secondly, the minute you do that, you’re of no interest to them ever, anyway. The truth is people like me who now live in the United States belong to that weird little ghetto of what my agent calls goddamned foreign writers. And living there, it’s always very clear that we’re foreigners, and Americans are not very interested in foreigners. Occasionally someone like Marquez comes to their attention. For the most part they’re interested in finding out about their own minority groups but they’re certainly not too interested in anyone from Australia.

RD: Can I ask you what living in New York has done for you in terms of language and imagination? Has it done anything?

PC: It made me very tense about language for a long time. I remember when I was writing The Tax Inspector when I was learning to make myself understood just day-to-day in New York City, arranging my sentences. We’re all so tentative and polite and say ‘excuse me, if it’s not too much trouble, would you mind if I had a bagel with butter, please ...’ In New York they go ‘bagel, with butter’. Not even ‘with’. Just learning to do that simple stuff ... So I felt quite tense and shy about speaking, so I was learning to say the word that would be understood. This happened to me for about two years. I read a lot of Australian stuff, I was so terrified. Now it’s a little bit like I’m someone who speaks two languages.

RD: Just to take your example of Americans saying ‘I want a bagel’ while you say ‘I was wondering if I could have a bagel ...’, I was wondering if that sort of thing might slowly be happening to your writing, where your narrative style, the way you address the reader, might change. But you clearly don’t feel this very strongly.

PC: No. The whole conceit of the book – placing the reader in the position of the Voorstander – was something I did quite late in the book in an attempt to clarify the political and social histories. I was finding it very difficult to get the historical and social stuff integrated with the ‘human drama’, and I was avoiding it, hoping somehow I could communicate it through the lines. I finally realised it had to be done head on, and this was one way in which, by addressing the Voorstander, you had to tell the Voorstander all this stuff about Efica. (‘You think this about us, but we’re like this ...’) I don’t know what this will mean to American readers to play this out. To Australians that’s not at all uncomfortable and the English, I’m sure, will not have that problem, but I don’t know what it will do to Americans.

RD: What about the dates business? You invent a different calendar which starts with the founding of Efica. It’s very important to you because you observe it all the way through. Was this to muddle the reader and discourage us from placing Efica and Voorstand in too real a world, geographically?

PC: I guess you could say, crudely, it’s throwing dust in the eyes, isn’t it? But if you have to start relating it to real world history, you’re creating problems you don’t need. Similarly, if I’d had to draw a map of the globe and place these countries on it, I’d be in serious trouble, because then you’ve really got to invent the whole damned planet. Having this Efican calendar lets you avoid having to confront the limitations of world history.

RD: Concentrate on the allegory, in other words ...You are a very carnivalising sort of writer and 1 was wondering again whether New York, which is like a big carnival in some ways to someone from the provinces like me, was going to intensify the carnivalesque in you as a writer.

PC: Well I don’t know. I don’t know where this is coming from in this book can’t tell myself. For instance, the theatre stuff ... I mean, I felt very timid at first about theatre, even though my wife is a theatre director and we’ve been together for nine years. I’ve learned to stay awake, in the theatre, and I know a lot of actors, and talk a great deal about theatre I always feel like this at the beginning, that I have no right to write about this. Certainly the theatre stuff in this came slowly and with some difficulty. With the Voorstand Sirkus there are two shows described – one at the end, a water circus. I figured out the performance would all be under water because I thought the Dutch have had this great fear of drowning, you know, the deluge and the inundation of the land. So maybe the Voorstanders carried this fear with them to the new country and that that fear is acted out in the Sirkus, and so I was able to construct a circus in which the fear of drowning was a major theme.

But there was an earlier performance of the Voorstand Sirkus in Efica, where I had to imagine what the Sirkus would actually be like. I avoided these things for a long time and the Sirkus was very theoretical for me. So finally, in both those cases, I confronted it. I guess I’m trying to say those things came to me with some difficulty, but because of that I did work on them very, very hard and very self-critically. Now I’m quite proud of those two glimpses of the Sirkus, which now seem to me to have grown out of the demands of story, rather than the influence of life on me. Indeed I feel some sort of timidity in approaching them.

RD: But it’s interesting how, when you feel a demand from the story, your imagination does something that virtually no other writer’s imagination does. You seem to be able to fly off at angles and land on other planets in a way that other people can’t. Most of us are very anchored to the world we actually live in. But even when you’re writing about a fairly real world as in The Tax Inspector or Oscar and Lucinda where you’ve done historical research, somehow or other your imagination is kaleidoscopic in a way other peoples’ are not.

PC: I realise that’s how I approach my novels. I don’t come at them at first through character, I come at them through idea. It’s as I explained about the water Sirkus. My way into it is a reasoned logical thing, and each step in that uses what seems to me to be a logical process. If this history is so, then how would it be ... if one wishes to have water and an audience, how would one do it? How would one get the air to them? If it is about a fear of drowning, how would you present that? How would it begin by being funny? How would you combine the electronic, video imagery and holographs with actors? I had said that there are both – well back, well before I had to think how it might work. How would you actually combine the live actor with the holography? So it’s structural...

RD: So it’s not just a great big explosion in your head at two o’clock in the morning.

PC: No.

RD: That’s comforting in a way.

Comments powered by CComment