- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: A venerable war journalist

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

The celebrated journalist Peter Arnett’s new autobiography Live from the Battlefield partly solves one mystery for me. For the last eighteen months, whenever I discussed Arnett and his forthcoming memoirs with my husband (who was trying to research Arnett’s relationship with news network CNN after the Gulf War), I found myself constantly and inexplicably analysing Thackeray’s Vanity Fair and the characterisation of the ambitious, fragile Becky Sharp.

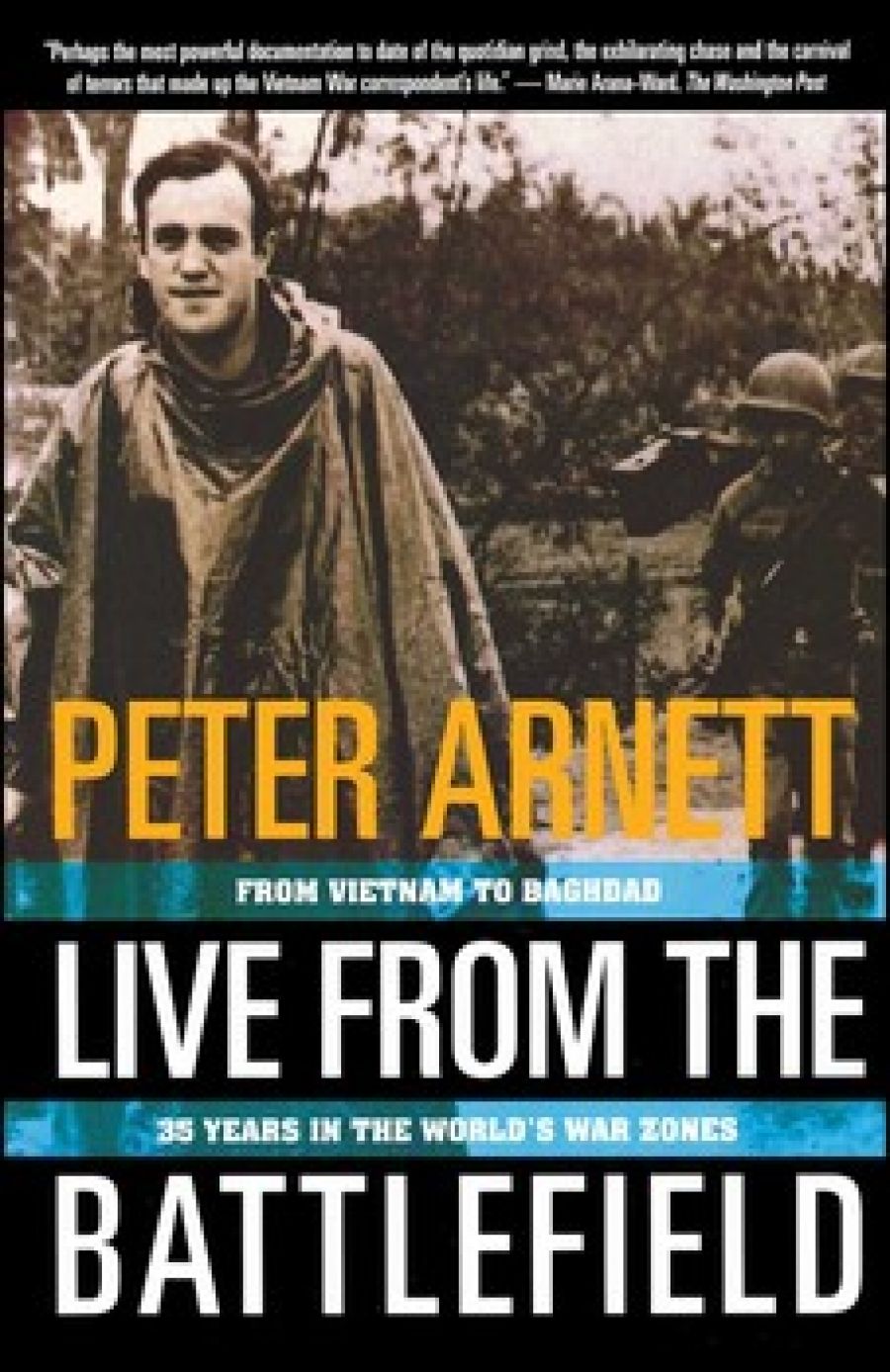

- Book 1 Title: Live from the Battlefield

- Book 1 Subtitle: From Vietnam to Baghdad, 35 Years in the World's War Zone

- Book 1 Biblio: Bloomsbury, $39.95 pb

Apart from illuminating (or complicating) my Becky Sharp puzzle, however, Arnett’s autobiography is layered with unsolved mysteries and dogs (perhaps like the dogs in Patrick White, kicked because of what they have seen) which don’t bark in the night. Not that this makes it a less powerful volume. Like that other small, bald, polite, sallow, deep-eyed watcher, Death in Bergman’s The Seventh Seal, Arnett bases his potency on his lack of analysis, disclaiming any knowledge beyond the physical facts.

The selection and focus of these facts, however, can be questioned. While in no way patronising or pathologising Arnett as being principally a Torture and Trauma survivor, I was reminded by his writing of the early drafts of many of the intelligent professionals I’ve worked with as gadfly writer-in-residence at the NSW Torture and Trauma Rehab. Unit, and many other literary workshops. I’ve read few other published or unpublished autobiographies which gave me the same sense of rigid ego-boundaries between the writer and reader as this one. The attitudinal style never softens into self-discovery. Surely his editor could have kneaded the dough a little, let in some air? The relaxing questions (‘Who were your father’s friends?’, ‘What did your mother look like?’, so many I’ve assembled a T&T manual of them) don’t need to be awkward or intrusive. The new facts don’t have to be value-judgements.

This lack of sense-data is particularly distancing in the account of Arnett’s NZ childhood. There are invincible flashes of life, as in the photo of his Maori great-grandmother, ‘her dark mischievous eyes challenging the world’. But of the prestigious, despicable Waitaki College, he only manages:

Waitaki Boys High was run like a boot camp for unruly children. [It] attracted a clientele both of genteel parents anxious to give their heirs a helping hand up the social ladder, and successful businessmen and farmers. It fielded a competent, generally sympathetic staff. But the pretty English gardens and handsome sandstone facade hid a repressive authority determined to go to great lengths to rein in and rein over youthful excess. This outlook enlivened the novel Tom Brown’s Schooldays, but to read about it is not to live it.

I remember the darker side of my boarding school days intensely. The record will show that most students survived the experiences, indeed are convinced that it made them better men and citizens. They regret the ending of the disciplinary traditions in recent years. I don’t.

No, indeed. In fact, he could have added that Waitaki was a soul-freezing archipelago of Greeneland which produced haunted people such as a mildly successful poet (Charles Brasch) and a much more successful Russian spy (Ian Milner, the headmaster’s son). It was obsessed with war (the dorms were named after First World War battles), welted by corporal punishment (and its consequent complex emotions of duplicity), riddled with chronic germs, and naked to the painful sea weather. When Arnett was there, it was probably also conflicted by the ghosts of two incompatible ideals. The powerful Headmaster Frank Milner was obsessed with promoting the British Empire and the League of Nations, and stocked the Library both with addictive imperialist fiction such as Kipling and much more dry Internationalist magazines, In other, Americanised forms, these two ideologies – maybe now in balance – seem to inhabit Arnett to this day.

Arnett doesn’t mention his Waitaki reading here (why did no one ask?) but elsewhere he has said, ‘I was Kipling’s “Kim”’ – and the idea would have signified for other reasons.

Kipling’s Kim is a clear-eyed British child brought up as .an Indian street boy in the Culture of the Raj, first guiding a holy man nimbly and then embroiled in the notorious ‘Great Game’ of powerplay between Russia and Britain for Central Asia. The last chapter of Arnett’s memoirs and his carefully timed return to CNN concentrate on the after-effects of CIA plotting and funding in Afghanistan, in terms of brutal local feuding and the training of Muslim Fundamentalist terrorists. He inevitably links this in with the N.Y. Trade Centre bombing and the CIA assassinations in Langley, Virginia. The whole TV package was delayed to coincide with his autobiography, and is very interesting, very tight and very inoffensive to all but sceptical N.Y. lawyers and devout Muslim radicals.

It was the safely manoeuvred return he may have decided he needed after his last Baghdad stand-ups in 1991, when he criticised the vindictive effects of UN sanctions.

As in the Great Game itself, however, Arnett’s Afghan account in this book and on CNN favours one Afghan military leader over another in a rather Edgar Wallace Sanders of the River manner which Kipling himself (in his greatest piece of writing) outgrows for an unusual metaphysical humanism, at Kim’s conclusion. There, the old holy man transcends his own hard-won nirvana and re-incarnates as himself to save the stripling spy Kim, his individual beloved. It is one of the most beautiful examples of total dehierarchisation in all literature, and Kipling never approaches it again.

Which brings me back to Arnett’s engagement in what Joyce (in Finnegans Wake) calls the ‘penisolate war’ of writing. There is an imposing and dismissive profundity – even a macho exclusiveness – about any accumulation of disasters, as Sophocles put it at the end of Women of Trachis:

Women of Trachis, you have leave to go.

You have seen strange things,

The awful hand of death, new shapes of woe,

Uncounted sufferings;

And all that you have seen

is God.

(From the Watling translation)

As a critic, I felt I had sometimes to brace myself by summing up all my own childhood horrors, and adult ecstasies and torments, to confront the Arnett style without, in R. D. Laing’s phrase, ‘Inauthentic Guilt’.

And Inauthentic Guilt is an occupational hazard for Warcos themselves. Despite his genuine reporting in China after his contrived persona in New Guinea, it made George Johnston feel such a ‘voyeur’ (Arnett uses this word once, too) that he abandoned journalism for fiction. But it still chimes through his My Brother Jack trilogy like the knoll of retribution, depriving his work of the full self-forgetfulness of art.

I’ve noted the same residual chronic unease in other Observing Professionals who have often had no authority to make decisions in a crisis. Many old midwives, paramedics and nurses have a firm, gentle, sceptical quality like old Warcos, and are also seriously scarred from their work. The Cynical Toughened Reporter (still lurking in Caputo novels) is an American myth, of course.

Inauthentic Guilt may be one reason that some Warco’s styles are at their most precise and artistic when describing their own physical pain. Tim Page (who worked with Arnett in Vietnam) does this superbly in his underrated autobiography, Page after Page.

But the Penisolate War ... There is no need to presuppose a ‘dark’ torture earlier than Waitaki to take into account the NZ childhood atmosphere in which Arnett grew up. Arnett has Maori ancestry, but with ‘Polynesian blood enfeebled by intermarriage’, and he says,’ outside the house I lived in a land that hundreds of thousands of settlers had turned into a mirror-image of England. My parents were lovingly insistent that I brush my teeth, eat my greens and keep practising the piano.’

Sylvia Ashton-Warner has written about Arnett’s generation, and the difference between Maori and White children, in her autobiographical Teacher. She describes a white child named Dennis:

... in a nursing home with a nervous breakdown. Plunket upbringing [footnoted as a method of child rearing successful physically but disastrous psychologically J and a young ambitious mother bent on earning more and more the picture I have of his life waiting for him, ... pursued by the fear unnameable, is not one of comfort.

Of course, Arnett wasn’t Dennis, but as a child he did win the Bluff Anglican Church’s Bible Study Prize five years in a row and his father, he says, ‘planned to educate his children to a higher level of achievement than anyone in the family or the town before’.

Whether or not one sees Arnett as a T&T survivor of a ‘repressive’ childhood, the quest for a safe position in a benign hierarchy and his unease and iconoclasm upon finding one are a constant theme in his memoirs. He has trouble on the Wellington Standard when he criticises the efficiency of his National Service Command, and is later fired by the Sydney Sun. His self-justifying account of this unconsciously confirms Pat Burgess’s version in his autobiography Warco that Arnett was still sensitive and defensive about it in Vietnam, explaining other colleague characterisations that he seemed as ‘hard-boiled as a ... Chinese egg’ by then. In Burgess’s version, the News Editor told Arnett he would never be a journalist.

He has problems with various institutions in various countries (including expulsion from Indonesia) until – well before CNN in the 1980s and 90s – he settles to work for Associated Press in Vietnam in the 1960s, and lives on a tightrope between the Authorised USA Version of the War and the reality he sees and hears on the ruthless battlefields and duplicitous streets.

Whenever I teach journalism, I have always found Arnett a rich catalyst for useful classroom debates. In particular, I like to read out bits of his 1970s college lectures about watching a monk self-immolate in Saigon, photographing and reporting it objectively without interfering. Then I read from Bowden’ s wonderful biography of Neil Davis, which quotes Davis’s engaging taped version of himself and Arnett rescuing a South Vietnamese officer and his son by forcing them on to a bus during the fall of Saigon. These accounts do inspire lively verbal sparring about when and how journalistic intervention is desirable, but Arnett’s autobiography disturbs me regarding the latter incident. His version of it does not involve Davis but one of Arnett’s AP colleagues, and it becomes much more an evidence of Arnett’s generalship, presence of mind and persistence than in Davis’s more naturalistic account. Strangely, though, Arnett seems more attractive in the Davis story, repeatedly crying out to the bus driver that the imperilled Vietnamese father was ‘the AP Photo Chief’, and earlier confronting a Vietnamese officer rationally and with courage. My first reaction was that Becky Sharp’s dark mischievous eyes had discerned the prejudices of the American market. Then I reflected that Davis had been the unofficial dope-provider for half of journalistic SE Asia, and it seemed impossible to learn whose memory had clouded. Anyway, Davis is dead and Arnett is hierarchised beyond asking.

It is true that Arnett also doesn’t mention Davis’s role in filming General Loan’s extraordinary street execution, or really do justice to Davis’s immortal monopoly in filming that Vietcong tank entering the gates of the Presidential Palace (a scene, I believe, at which Arnett’s later media rival for Baghdad, Tom Aspell, was present but lowered his lens out of caution). But an autobiography is by one man, all in all.

So back to the Penisolate War and the Burning Monk Business. Arnett’s rationalisations for not interfering are gentler here than the fierce objectivity he preached after Vietnam, perhaps taking into account his growing post-Baghdad USA middle-liberal power base. Nevertheless, it also seems because of a much more likeable lapse into self-reassurance. Certainly the rationale now is that the Buddhist monk and his supporters would have abhorred any interference (and been murdered by the Saigon police anyway) but really Arnett’s action narrative stresses that Arnett was too startled and transfixed to react very much physically.

His narrative technique for the immolation incident is well worth analysing, as it is typical of his memoirs’ style for action sequences:

As the taxi sped off, the man pulled a small jerry can from his bag and squatted down on his haunches in the lotus position. The tiny yellow flame flickered as he touched it to his garment. He returned his hands to his knees, making no sound at all, even when the red flames burst around him. As the blaze leapt up to his face, I had to back away from the searing heat. I saw him wince and grit his teeth, but that was his only expression. But I was remembering Madame Nhu’s mocking description of these Buddist immolations as ‘barbecues’. I clicked my camera a Jew times and tried to make notes but my hands were shaking with terror. Essoyan was ashen-faced next to me. A low moan rose from the gathering crowd. I heard a woman laugh hysterically ...

This is not the style of Arnett’s early despatches, even those that won the Pulitzer. His earlier wire service style (still surprisingly distinctive) used conventional truncated sentence action build-up (mirroring and re-creating quick breath and pulse-beat) interspersed with a few (sometimes well worn and slightly inappropriate) similes, such as’ moths to a flame’. I realised the pacing function of Arnett’s early similes when I was looking at H. B. Gullett’ s impressive Second World War memoirs, Not as a Duty Only. Gullett stylises his narrative to convey speed and stoicism, with relentless volleys of short sentences. But as compelling as it was, Gullett’s style wasn’t physically reproducing the rhythms of danger.

These are, in fact, best reproduced in a slightly longer but reliable rhythm interspersed with dying reflective fall – like that moment after falling asleep when one’s lower blood pressure makes the heart seem to pause unpredictably. Arnett’s action prose is really a sequence of classic iambic stresses in a predictable single adjective and noun pattern, interspersed with a stretch of slow trochees (replacing the earlier similes) which both grip and destabilise the reader’s response. It works very well.

There is a surreal quality in Arnett’s writing that comes from his perfect attentiveness to the confounding of his expectations. He is evidence of my favourite Simone Weil aphorism: ‘Moments of attention and insights of genius are not different in kind.’ It seems doubly sad that he hasn’t turned that objective attentiveness to wider areas. Or, since his career seems so enormously timed, planned and disciplined, perhaps that’s what he has done, in the confidence of this effort’s success.

In the meantime, when Arnett’s attentiveness lapses and the long lists of sequential generalisations take over, the prose degenerates into the memoir one might expect from Henry the Warco in Drop the Dead Donkey:

Bangkok was also my finishing school for sensual experience. The rich colours and smells and sounds were an intoxicant that liberated the libido.

Of real sex he writes nothing yet. He must be wary of the fact that in USA culture to sexualise something is to trivialise it. Perhaps he meant to write of it, because he has set a stage. Surely few journalists could forget him at the Washington Press Club after the Gulf War, brandishing a Sydney Daily Terror front page picture of his fiancée dimpling down at him with exactly the same expression of mischievous tenderness as Bernini’s Angel stabbing St Theresa, and the whole thing entitled ‘Baghdad Peter’s Kiss of Love’? The tone was not The Blue Angel but of someone dancing before the Arc of the Covenant, and the persona wasn’t Indiana Jones.

The genuinely important lapse in style and self-confidence in Arnett’s autobiography is his need to establish the persona of an action-hero. I was astonished at how often Arnett uses the verb ‘figured’ throughout. It was a verb I tried to dodge for my own thriller hero, as I thought it would make the writing sound too much like a genre whodunit. Even if this stereotyped diction is intended to appeal to the USA market, Arnett’s action-hero persona keeps slithering out of place attitudinally. Shortly before pretending middle-aged surprise at his young colleagues’ carton of condoms (although there are winking references to girlfriends and bar-girls throughout the book) he is shopping for supplies in Baghdad with the producer, Ingrid Formanek: ‘She stocked up with superior brand whisky and cognac. “The minders”, she said, “drink like fishes. They’re more interested in this than sex.” I figured Ingrid would know.’

‘Miss Ingrid’ was the ribald but, apparently, frigidly chaste heroine of Live from Baghdad, the skilful Hunter S. Thompson-esque book by Arnett’s producer, Robert Wiener. Arnett’s sour innuendo badly undermines the tolerant, experienced characterisation Arnett has established in general. Arnett tends to exude enormous maturity almost inadvertently; an admitted sexual maturity would have solved much of the book’s attitudinal unsteadiness.

In fairness to Arnett, many Greene or Le Carré-style fudge-constructions like ‘a kind of’, ‘something like’, and ‘of course one knew’, aren’t present here, and could be. The photo of Arnett by Annie Leibovitz in December’s Vanity Fair made him look like Alec Guiness in a designer trench coat. The new USA ‘Arnett legend’, as he calls it, may be like nothing on earth.

The Leibovitz photo is reinforced by a David Halberstam article praising Arnett’s character mightily and saying little about the book, except that it is ‘the exceptional testament of a magnificent reporter’. Halberstam repeats his usual comparison of the young Arnett to Jean-Paul Belmondo and reflects, ‘How Arnett found the inner strength to keep going ... I do not know. Arnett seemed to get stronger. And he never lost. He grew as a man as well, I thought ... emerging [with] infinitely greater subtlety and sophistication.’

If we’re considering movie stars and subtlety, it occurred to me that Arnett’ s boyhood modelling of himself on Marlon Brando has come true in his 1990s TV appearances, where his face has softened and subtilised. It may be another example of Proust’s law that we only get what we want when we don’t want it anymore, or it may reflect a quality of grace.

The Halberstam piece seems to have been the fanfare in a huge American PR campaign, including the colour front page of the New York Times Book Review. This is the five-star limo of War Correspondence. Certainly there is the welcome aspect that many journalists are using the book to vindicate Arnett’s difficult position in Baghdad. I remember my irritation when the Australian ABC publication, 43 Days: The Gulf War stated that Arnett was trying to signal that the bombed milk factory (still not fully functional, by the way, in a malnourished country) wasn’t one at all. When l pointed out the reverse to the publisher, the chapter author Jonathan Holmes admitted that Arnett had judged it a milk factory, but no addendum slip was ever printed for remaining copies. Until now, the remnants of Arnett coverage have contained such confusion.

The new Arnett PR causes different problems. My husband had the devil of a time trying to research Arnett through CNN, which refused to answer letters or give any complete reliable information. Our only real information came from academic and external media sources, including the obliging Dean of Humanities at the University of Columbia in New York and the Editor of People magazine who faxed us an unpublished interview. This didn’t really solve much, as it quoted Arnett as intending to return to CNN months before he did so, and as having to perform on Dutch TV with Joan Collins and a trained seal (the latter proved true).

When I tried them, CNN seemed chilly and formal, and the organisation to be composed almost entirely of Vice Presidents and interns; I thought that maybe Arnett had re-found his safe childhood hierarchy at last.

His Washington PR lady, Lisa Dallos (yet another Vice President), had a crisp, patrician, threatened manner. I suspected an unofficial embargo on Arnett to coordinate his Afghan special with his book. To my written requests (sent with a copy of my last Penguin, which includes a respectful Arnett poem) the only response was a pleasant form letter and autographed postcard from Arnett – to my husband. I joked that the CNN structure resembled New Zealand, but future study of it does seem important, considering its influence as a news source. Arnett himself remarks: ‘There were younger journalists who felt as I did. Not enough of them were on CNN’s payroll.’

But the Penisolate War: there seems to be no doubt that there is an atmosphere of protectiveness around Arnett which may not always be useful to him. Arnett himself has written that CNN successfully ‘protected’ him from some of the criticism during the Gulf War. It seems to me that Warcos and other professional witnesses are certainly like Torture and Trauma survivors in that they learn an air of vulnerability to survive at all. When this quality clings over into everyday life, however, I think there is a danger that other people’s protectiveness will impede the growth of the survivor’s learning and artistic processes. Arnett has often been physically and politically defended by his friends, and he features this protective circle repeatedly in his conversation. For example, in his interview for the New York Times Book Review, he tells a story about Alan Simpson, the influential mid-west Senator who attacked Arnett’s role in Baghdad; Simpson, he says, told him at a party that he’d discovered Arnett had more friends than he.

But there is no doubt Arnett has built up a power base of colleagues. The status of being a celebrity perhaps offers a protected hierarchical place just below the highest level. You are very important but there is always some safeguarding from above. According to Arnett’s autobiography, AP campaigned thoroughly for him to win the Pulitzer in 1966, and when he won he wept abandonedly in bed as he had ‘never won anything in [his] life’. But this is a form of crying I associate with at last feeling safe. Arnett seems to practise that I like to think of as ‘the skyscraper method’ of witnessing: you brace yourself as little as possible and absorb the maximum impact of the events at the time to sanity-limit, like a skyscraper accommodating the weather, and then let yourself straighten slowly back into place.

To straighten back one needs to incarnate the senses very simply and there is always a strong element of luxury and hierarchisation in that. After a recent, deeply emotional Torture and Trauma workshop with Central and South American women, I went out and bought a metre of embroidered blue silk on special and hand-sewed it into a shift for my daughter so I could feel it trickle under my thumbs.

It is a pity that Arnett doesn’t mention his own need for artefacts in this volume. His bargaining and collecting is one of the most famous and intriguing things about him. Bargains are important. They are like little unexpected gifts or prizes from God, which point one in new directions. If one was a schoolboy in the slow starvation of Waitaki, one would soon learn sensibly to organise small divine gifts for oneself.

Arnett’s collection ranges from Luristan bronzes to a petite tenth-century Vietnamese stone goddess. Even the most factual attention to such treasures would have enhanced the volume’s breadth enormously, and delineated other aspects of war and endurance.

When considering Arnett, I pondered not only Becky Sharp but also Conrad’s Nostromo (which I trust is also jogging along in Arnett’s kitbag as the souvenir of some other shambles), and it seemed once again that Conrad was right about politics, however much I dislike his other tendency to stereotype evil in human form. When Conrad’s pure, radical-liberal Don Martin suicides on an island as he loses faith in humanity and in waiting for Nostromo, and when Conrad depicts the great character of Nostromo (impetuous, fluctuating, full of irresistible appetites, allegiances, emotions and ideals) as the one of the two which is politically humane and viable, I agree.

It is quite clear that Arnett’s residual irritation at the peace protesters in Baghdad is because of their anger at him, and he’s right to be irritated. Someone more ideologically acceptable to them would have lacked credibility and effectiveness; Someone less eager, less compulsively and necessarily corporate, less betrayed, less conflicted, less a perpetual restless vector, might not have wanted to be there. ‘All neuroses’, as Lawrence Durrell has it, ‘are made to measure.’

If this book is, as Halberstam says, ‘a testament’, it is composed of encrustations, cobbles from earlier drafts, blacking-factory avoidances (there is a Dickensian preoccupation with the seepages of the dead) and nervy contradictions. But its intention, existence and reputation for brave observational candour will certainly save souls.

Occasionally I have theories about an Afterlife (which is probably much easier to research than Arnett’s relationship with CNN) and one of them is that an Afterlife would in some ways be concurrent with this one, but free in time and multi-dimensional, like an autobiographer. One could visit one’s oblivious, incarnate self wherever one chose and freeze-frame some moment, with access to all of one’s being, at any level of feeling. And there is no doubt that Arnett the ideal autobiographer would freeze-frame himself for a long while in Vietnam and Baghdad, incarnating integrity ...

Then I close my eyes and the images are an archetypal spectral male figure – older and deeper than Hades or Jung or any Tarot – in front of his quiet queue of black, charred, wet bodies ... and of Becky Sharp at the last – caught up wistfully in the penury of the real Peninsular Wars, and still pursued by the fear unnameable.

Comments powered by CComment