- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Article Title: Loaded Terms

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

How do you give a plot description of this book without entering into the very language that it problematises? Ari is young, unemployed, Greek and gay ... Or Ari is a poofter wog, a slut, a conscientious objector from the workforce ...

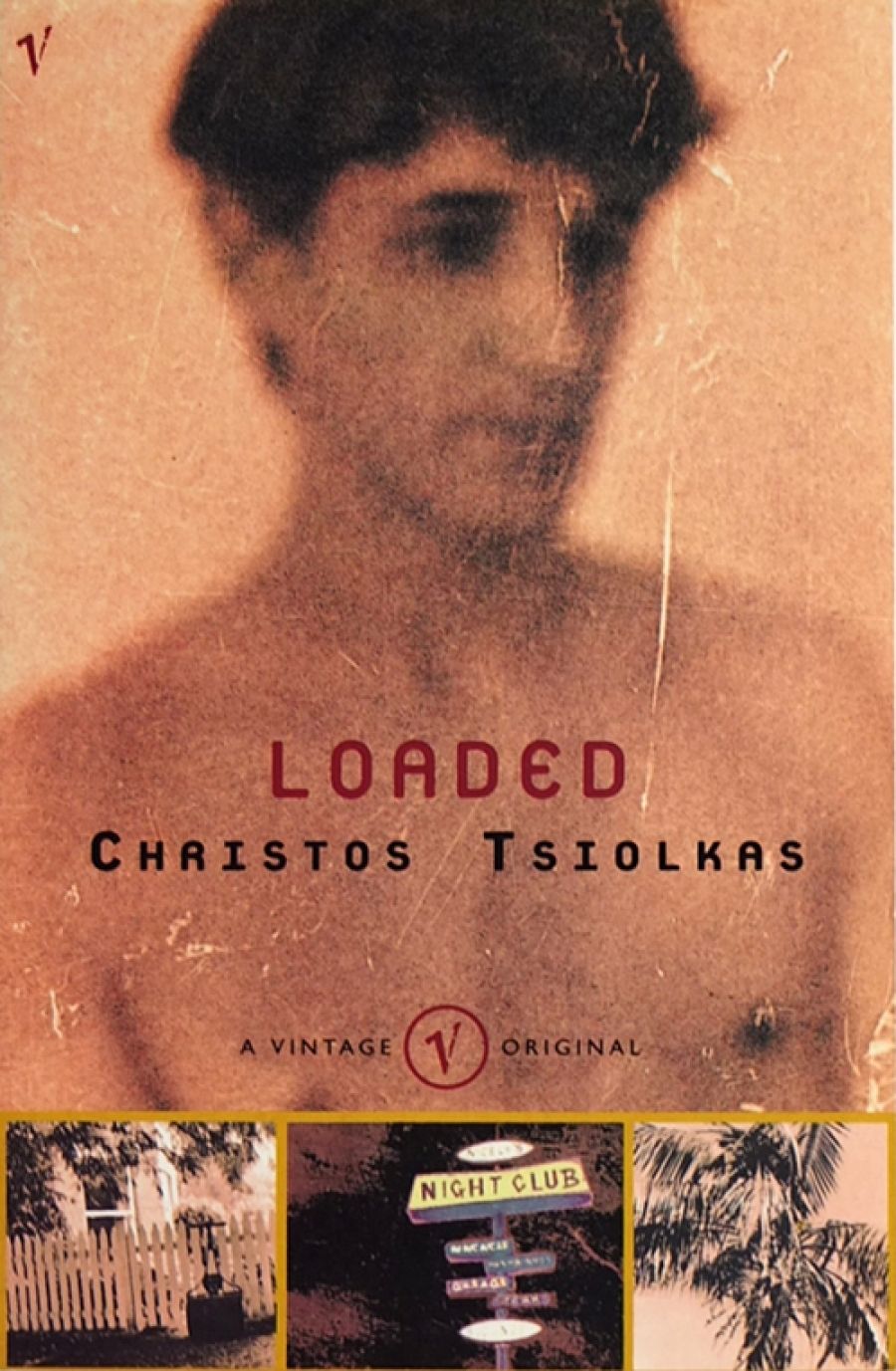

- Book 1 Title: Loaded

- Book 1 Biblio: Vintage/Random House, $14.95pb, 151 pp

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/do96EQ

I hate the problem of ‘authenticity’ as it’s often applied to writing by women, gays, blacks, and wogs, so that ‘too much’ artifice or brilliance then becomes a fault. Could an ‘uneducated’ nineteen-year-old boy, for instance, really be that articulate and wise? Unlikely, but who cares?

Certainly, there is a sense of deep recognition. Ari is most definitely moving through the city I grew up in. And his descriptions of dancing and being on drugs are great. It’s a very sexy, sensual novel, not in the sex-scene kind of way, but all throughout it. Ari is flirtatious, for instance, with his mother, and he can even get a hard-on thinking about the nuclear holocaust or sitting on a bus.

But does that add up to ‘realism’ (does anything?) I would have thought that it had more of an epic quality (he certainly takes a heroic amount of drugs); that it owed more to Brecht perhaps than to Dickens – especially in the use of distancing (for instance when Ari steals the Walkman) and the almost mythic quality of the cast of characters.

The idea of ‘Dirty realism’ also smacks too much of voyeurism, as if it’s just a window onto another world (not our world). And as far as its being a ‘subculture novel’: well, some of my all-time favourite novelists only ever wrote about subcultures – Jane Austen, for instance.

The book also owes a lot to European cinema and to a vast range of music; and it’s far too poetic to be realism. For instance, Tsiolkas has a wonderful technique of taking certain key ideas and replaying and reworking them through a series of montaged scenes – like a sampled phrase or riff in a piece of good techno music. Words like ‘wog’, ‘faggot’, ‘Greek’, ‘Australian’, ‘politics’, ‘history’, ‘pain’, ‘struggle’. And the phrase ‘weak, lazy, useless’.

Each scene undercuts or alters the way the phrase was used in the previous scene. Everything is provisional, like favourite songs. (Asked to name his favourite song Ari says, ‘Hard question. Favourite songs, like favourite films, like favourite people, change day by day, moment by moment.’)

There are lots of hard questions but no answers in this book, although it does have an ethics. Lacan once said: ‘I don’t have a philosophy of the world, I have a style.’ You could say perhaps that Ari has a style and a favourite tape, a soundtrack. The favourite tape being a kind of serendipitous unrepeatable accident, a tape made by delving into other people’s record collections.

In fact, Ari is like music, and like anarchism at its most basic, that which both threatens people and unites them.

‘I figured we all must have memories of that song. That’s a great song, Dina, one that makes you connect with strangers.’ He is a thief, a runner, a dancer, a DJ of historical moments, ‘the wog boy as nightmare’, screaming out ‘Face it, motherfuckers ... There isn’t a home anymore.’ He is a slut, a whore, a sailor in a country where ‘below there is only ice’. Johnny teases him in front of people by saying his drag name is Persephone.

Ari gets asked questions about who he is or what he is all through this book. For the first half most of the questions concern his ethnicity (Is he white? Or not?; Greek? Proud of it? Australian? Greek-Australian? Wog?). About half way through the book, when he goes from the Greek club to the gay club, the questions change.

She stands up and faces me. Her tone is aggressive. So what are you, Ari, she asks again, gay, straight or bi? Sasha gets up and grabs my hand. A slut aren’t you, Ari, she says.

--A slut, I agree. Let’s go, Sasha says, let’s dance.

Ari uses his sluttishness to try to escape or evade the impossibility on which his desire pivots: the problem of how to be a man and have a man.

Real men = danger, dominance, hardness. A mythic construction, a set of rituals and forms and tropes transported from another place (heterosexuality), a bit like the plastic wedding reception centres trying to keep alive European culture in the suburbs of Australia. Ari says, ‘the danger I face in pursuing my pleasures is the guarantee I have that I am not forsaking my masculinity, but danger in sex has always been the classic female position. Masculinity without an Other to reject or protect becomes a set of postures; signifiers without a sign, an unattainable desire. Ari only wants real men but if they find him desirable he loses interest because fucking them ‘feminises them’ in his mind. In many ways the systematic deconstruction of the idea of Greekness/Australianness/wogness in the first two-thirds or so of the book leads to this perhaps even more fundamental deconstruction of gender, of power and vulnerability. And the fact that Ari moves towards accepting that he might be in love with a man by the end of the book (a young ordinary man, not a Greek working-class patriarch) is important because it marks a radical re-ordering of his universe and of his desire.

It opens up more than just the possibility of romantic love in his life, it opens up the possibility of failure: of a struggle that might lead to nothing but is worth doing anyway.

I could go on about this book for hours, but I’ve used up my space. Read it – not as a window onto some alien other dirty nasty real world, but into our own.

Comments powered by CComment