- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘When I was eighteen my boyfriend’s father died in jail.’ This is the opening sentence of Ben Winch’s second novel; it is also the conclusion of the novel and, having got that out of the way, we can settle into the details that will tell us why this man died in jail and what his story means for this now eighteen-year-old woman.

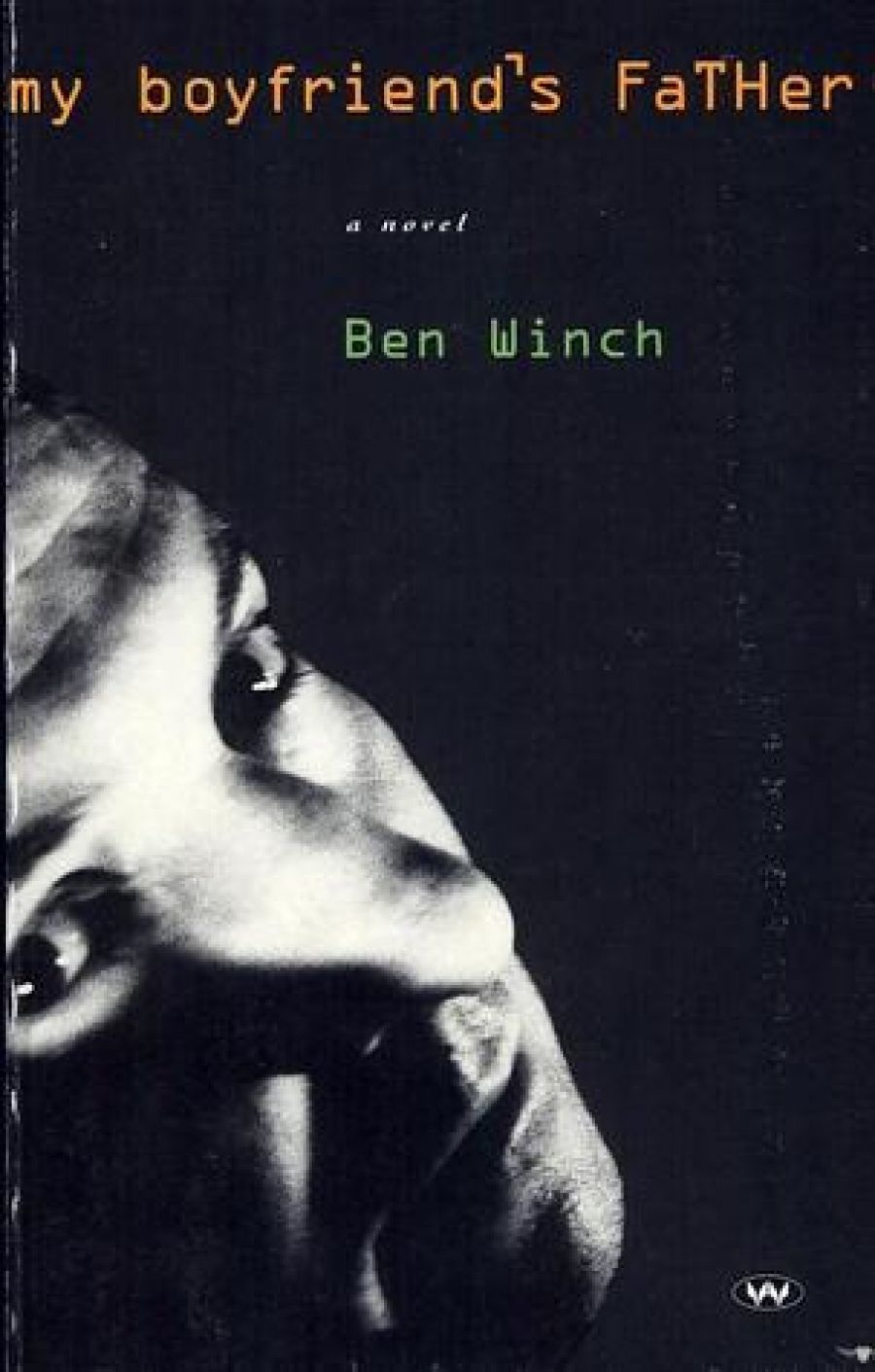

- Book 1 Title: My Boyfriend’s Father

- Book 1 Biblio: Wakefield Press, $16.96 pb, 222 pp

- Book 2 Title: The Man Who Painted Women

- Book 2 Biblio: Minerva, $15.95 pb, 329 pp

- Book 2 Cover Small (400 x 600):

- Book 2 Cover (800 x 1200):

Sylvia was sixteen when she met Phillip, her boyfriend’s father. It wasn’t long before he made an impression on her:

He offered me marijuana and I accepted. Dylan refused; he sat watching me with a mannequin’s expression. After a while Dylan grew bored (or so I thought; later I would realise that he was upset) and Marianne grew tired, and Phillip and I were left alone. I had got stoned at school, at parties, with friends, but never with someone’s father. I felt privileged.

From here we have Sylvia’s observations of Phillip, reports on the few details about him that she could get from Dylan or Dylan’s mother or his sister Elicia, and reports of her visits to his pathetic bungalow once he had estranged himself from his family. This novel comes alive (and depends for its life) on the sparks of Phillip’s monologues. His life is one long rave. The story matters much less for the reader, and the writer I suspect, than those wonderfully nuanced, convincingly documented raves. Once Phillip and Sylvia have ‘toked up’ on his dope he launches into one of his seventies-style raves and Sylvia gives him just enough encouragement. To meet him in someone’s lounge room would be to meet a boor but on the page there is the fascination of this word-perfect record of a man’s refusal to hear anything but the voice of his own adolescent rebellion. At first it is the self-defeating logic of this rebellion we follow in Phillip, but by the end of the novel his idealism has been transformed into the rambling self-justifications of an alcoholic. These ramblings are also captured with unmerciful accuracy. Winch’s novel shares with Margaret Clark’s contemporary fiction an air of documentary accuracy which makes it memorable.

My Boyfriend’s Father is a considerable advance on Winch’s first novel, Liadhen, because it does let its main character loose and let his fate play itself out in front of us in its most sordid and embarrassing moments. Phillip is ultimately a detestable character – and it is a novelist’s challenge to keep us reading when the hero is a failure, a sleaze, a liar and a tiresome ear-basher – but I read on with fascination as his increasingly pathetic life was detailed for us. Phillip’s diatribe on Peter Carey and his book The Tax Inspector is hilarious. It’s worth buying the book for this rave alone.

Though the novel belongs to Phillip, the story is told by Sylvia. As with any first-person narration, Winch has had to choose whether he will foreground his narrator’s character and voice or hold her back as a pale figure through whom the story can shine. Impressive observer though she is, Sylvia doesn’t develop as a character. This might have something to do with the general flatness of the prose whenever we leave Phillip’s voice. As she and Dy Ian become lovers, for instance, there is, in Sylvia’s voice, the sense of someone carefully reporting the facts -an oddly chilling effect. The malaise of youthfulness which hangs over Liadhen is here again in My Boyfriend’s Father.

John Newton’s second novel, The Man Who Painted Women, is also narrated in the first-person. Newton has chosen to focus his book on the voice and character – and life – of his narrator, Rafael Pizarro Guadiana. This book is a monologue. Rafael is a self-obsessed and sex-crazed genius, and he lets us know this on nearly every page. At the time of writing his manuscript as a seventy-one-year old suddenly impotent painter on a Mediterranean island, he is the most admired artist in the world since Picasso. In fact he was once a protégé and intimate of Picasso. He even slept with Picasso’s famous mistress, Marie-Therese, and he might be the real father of their child. Picasso introduced this Pizarro to Gertrude Stein. Pizarro also painted a portrait of Stein, a nude portrait. At every turn he shows he has surpassed the master.

Françoise Gilot reported in Life with Picasso that he was fond of saying, ‘For me there are only two kinds of women ... goddesses and doormats’. Pizarro goes one step further than the master: he comments that Picasso’s mistake was ‘in never understanding that they are both’. Women are naked and defenceless throughout his life. When he tells of raping his first master’s mistress her kimono is both a mere stage prop and a sign which later links him to Picasso.

I don’t know how long I sat there enveloped in rage, in the eyes of the raven, and those rolled-down stockings over the strong legs. And then, for the first time, anger became lust, furious uncontrollable lust, as easily as a frown is changed to a smile with one brushstroke. I stood and moved over to her. She cowered. I ripped off the cord of her kimono. Within seconds I was on her and in her.

Years later he will witness Picasso beating his wife Olga Koklova as she faces him wearing only a crimson kimono. We can see that Pizarro is Picasso. Both of them paint Woman because they cannot understand or love women.

This is all very well, perhaps. John Newton says this novel arose after seeing an exhibition of Picasso’s etchings. He wrote it, he says, to explain to himself ‘why men hate, misunderstand, envy, want to possess, dominate, control and are generally bewildered and bewitched by women’. Yes, I see. John Newton’s epiphany offers him the chance to construct for us a portrait of a bewildered but still unrepentant misogynist-genius. He goes to great pains to describe the fucking, raping, whoring and humiliation of women by Pizarro and Picasso. But to what end? I waited for the explanation to arrive. What happens to Pizarro? Does he come to see what he is? What is he anyway? Poor Pizarro loses his ability to achieve an erection - and this loss provokes him into writing down his memories of all the women he has painted, though he admits he has forgotten everything about most of them. It is like a yarn from an eighteenth-century rake. And in the end it seems to me he is as frightened and bewildered as he was at the beginning. Is there no redemption, no way out of this? When he is dressed in the end in the black dress of his sister (his first lover) and the pants and chemise of a young woman from the village, with his face rouged, I am not convinced that he has found a way out, or a way-back.

Comments powered by CComment