- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

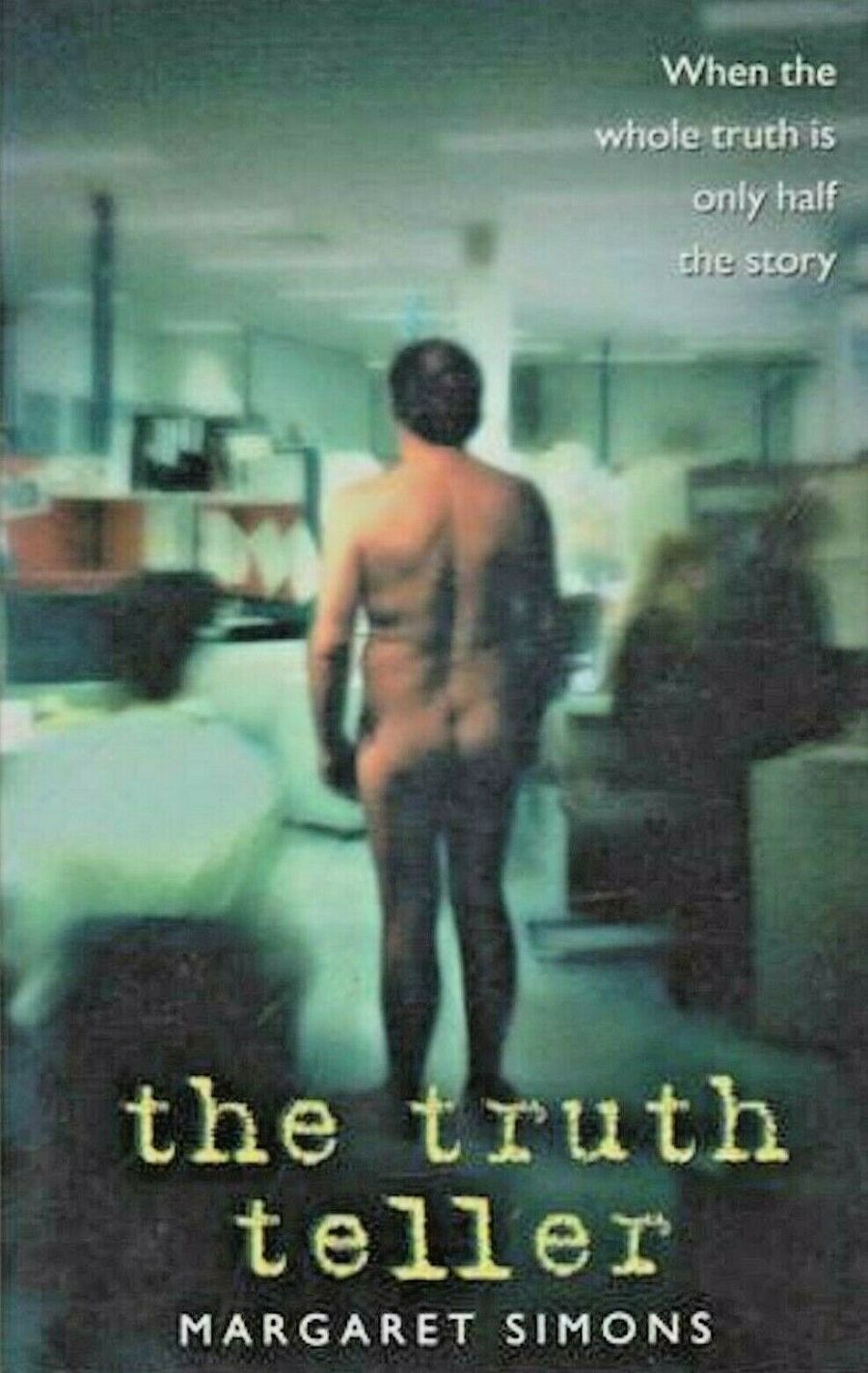

The Truth Teller is a novel about a man hiding from himself. Told with pith and passion by Margaret Simons, it chronicles the career of journalist, Simon Spence. Spence lives in an exterior world. He hides behind facts and what he understands to be the truth. But Spence’s truth is a public one, not private. His private truth lurks far beneath the surface, suppressed by the very nature of the journalist’s ‘truth telling’ work. Simons writes about a world she knows, as a former journalist on The Australian. Her crisp writing style is ideal for the ambiguity of the subject. With razor-sharp words Simons sends messages that are as soft and blurred as clouds. She conveys the subterranean urges of the soul (‘the earthworm heart of a man’) as concisely as the fast-paced media world that buries it.

Against this background Simons weaves a complex web. Layers of age-old questions (What is truth? What goes on inside us? Can words express our true feelings?) stack up as each character is introduced and developed. Her characters cover the gamut of emotional involvement – from the obsessively inquiring Pru to the queerly conniving Killinger and the burnt out narrator, Ophelia Balls. Spence’s complications hang in the middle of the web, trapped like a fat fly. From age six Spence is focused on becoming editor of The Mirror. This fictional Melbourne newspaper is aptly-named because it reflects his understanding of the world – black and white inked pages describing right and wrong. Flat and declarative. Spence’s whole raison d’ être is in this medium, outside himself. He files feelings away like he files his Queensland police corruption stories for The Mirror. Spence files his feelings for ex-lover, Pru, under ‘I’ for irrational:

Spence felt a stab of guilt, a nudge of jealousy and a quick pain. Then, almost before these feelings had registered, he had told himself he felt none of these things. Why should he? It was irrational for him to feel that way, and therefore he did not feel it... A second more, and he had forgotten that he had felt anything at all. Had you then asked him how he felt, he would have reflected and found a blank.

Ophelia observes: ‘He spoke like a typewriter. I had to return the carriage with my little words of prompting so he could speak again.’ But even the journalist in Spence, the part of him that seems straightforward, is blurred:

For a journalist he lacked curiosity. He wanted to shake rather than coax the truth out of things. When he wanted something from others he resorted to silence and they were forced to advance towards him.

Simons regularly refers to that journalistic catch-cry ‘just the facts ma’am’, as much in parody of Spence’s inability to express his inner-self in words as to remind the reader not to take things at face value. It reinforces an underlying message – nothing is as it seems. For example, the mateship between Spence and his colleague Killinger is simple and straightforward on the surface. Their blokey conversations are skeletal and unambiguous.

But darkness and irrationality lie somewhere underneath – the very first sentence of the prologue states Killinger is insane. Simons’ direct style forces the reader under the skin of her characters. She has Ophelia tell the story of her abortion then fire questions straight into the reader’s face:

Can you imagine me as I sit there, on the bus, bleeding in little spots. Can you imagine Ophelia Balls? Tell me how I look. How I feel now. Tell me what I left behind in that stainlesssteel kidney dish...

Simons demands an inward answer from the reader, just as Spence and Ophelia are finally forced to examine themselves. Consequently the reader gets a taste of the turmoil inside the main characters.

Much of the novel’s colour and strength comes from its metaphoric threads: the comfortable corner pub with its frosted glass windows shielding Spence while he loses himself in an alcoholic haze; his recurring dream of the tide washing away blind men stuck in the sand; the dreamy underworld of the sewers; the oceanic references that describe both Spence’s floundering soul and the details of the sexual act. Sexual tension is never far from the surface. Simons uses it as a main thread in the web and it is continually re-emphasised by newspaper jargon.

Cynics may find a happy ending hard to believe after so much psychological chaos. Sceptics may be left wanting on the subject of media corruption considering police corruption is an integral part of the novel’s structure. But overall, The Truth Teller plants thought-provoking seeds in the mind that continue to grow.

Comments powered by CComment