- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

I approached this collection of essays with some sense of anticipation, thinking ‘Do David Williamson, Beatrice Faust, Jamie Grant, Frank Moorhouse, Les Murray, and Christopher Pearson have something in common? If so, what?'

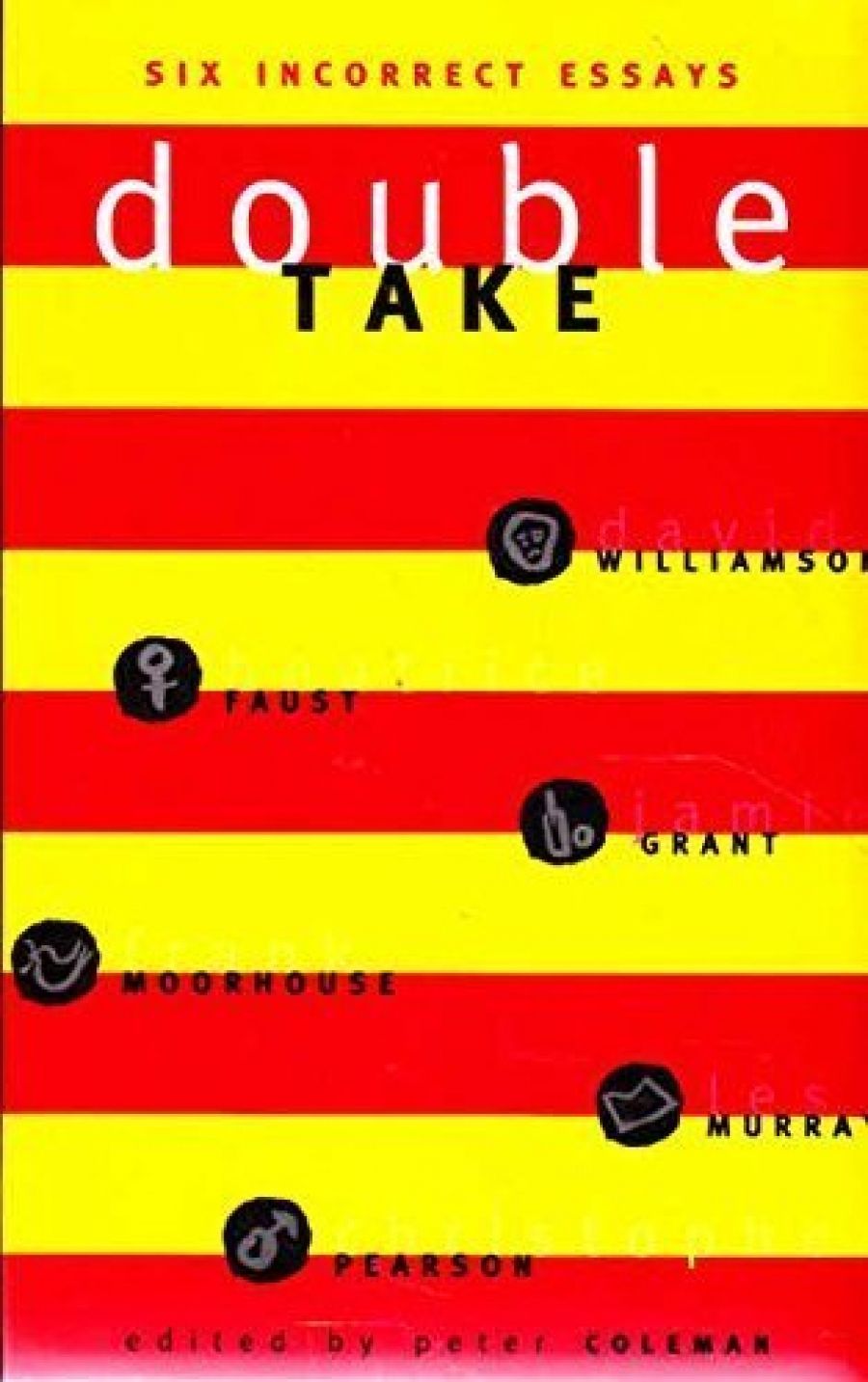

- Book 1 Title: Double Take

- Book 1 Subtitle: Six incorrect essays

- Book 1 Biblio: Mandarin, $14.95 pb, 194 pp

Forget all that you have read in the big circulation daily newspapers, it would seem they have been swallowed whole by the Politically Correct, if that paragraph means what it says. Or can it be that he discounts the communicable power of media cynicism – which has publicised the phrase Politically Correct to the extent that it is now a joke label except perhaps in the sheltered workshops of Academe or the Federal Public Service?

Coleman has a taste for little slogans intended to simplify: ‘The (recent) outbreak of freedom of thought in Australia was contagious’, for instance. He is trying to tell us that we had been living through something like two decades of thought-policing. ‘If you did not conform, you would not get a bullet in the back of the neck or end up in a labour camp, but you would be defamed, boycotted, and marginalised’. But, writes Commander Coleman, ‘So widespread was the new, unruly Political Incorrectness that even the Australia Council could not dampen it.’

Hey, wait a minute! This smells of killing the messenger. I know that the Federal Public Service does have style manuals on non-sexist language, and non-discriminatory employment guidelines. The Australia Council has a multicultural strategy – perhaps multiculturalism is the secret common denominator in these ranks of the self-proclaimed Politically Incorrect? But no, none of these essays wants to muddy those waters. (Unless one counts Jamie Grant changing the name Lew Hoad to Lou Hoad – from the Welsh to the Continental, perhaps?)

This collection, I thought, must be to demonstrate some of the safer specifics of the brave new Political Incorrectness. Let the wounds be displayed and the injustices brought into the demilitarised zone of Double Take.

David Williamson, in ‘Men, women and human nature’, gets things off to a rollicking start. His play Dead White Males has become, as Coleman quixotically admits, ‘the most popular Australian play ever staged’. Williamson’s essay is a fascinating and useful crib on the sources and resources used in that play. Other playwrights would give an arm and a leg (and probably a left testicle or right fallopian tube) to get a fraction of his publicity and media space – including the drubbings.

Williamson’s theories and referrals to support a liberal humanist viewpoint are nicely marshalled but when he refers back to the concrete and the immediate he does so with a dramatist’s skill:

Political correctness is also anathema to true literary creativity. It imposes a mental set on writers that demands they dispense with all explanations of human behaviour that might rely even partly on biology. The sexual excesses and violence of young adolescent men must, for instance, be sheeted home to a lack of sufficient quality of fathering or some other environmental cause rather than the realisation that it might have something to do with the fact that the testosterone levels of sixteen-year-olds are fifty times that of a fifty-year-old.

Similarly, Williamson can achieve more by one graphic example of editorial censorship to convince readers of the covert dangers of self-imposed ‘correctness’ than through any number of learned analogies or painstakingly marshalled ‘discourse’:

some years ago when attending an International Writers Guild conference in Wellington I was shown a copy of a document from the drama division of the New Zealand Broadcasting Corporation which outlined the way women were not to be depicted in any fiction. It was, as I remember it, a twenty-point checklist which included the instructions that women were not to be depicted as overly emotional or anxious, and were not to be shown in the kitchen or preparing food in any part of the house.

There are too many tales of similar ‘guidelines’ in the Australian publishing and media world not to make any author prickle with hostility at such disclosures. In a recent Penguin anthology, I discovered that references to a ‘policeman and policewoman’ in a short story of mine had been (without any consultation) replaced in the printed text by ‘policepersons’.

As for the NZ ‘regulations’, they sound like a guide-sheet from Mills & Boon, directives arising from capitalist impulses at their most determined, not from any wicked New Left theories.

Jamie Grant, in ‘Give Us Back Our Sport’, offers an account of the innocent cricket enthusiast discovering the true colours of capitalism in its oldest, and newest, manifestations when his love for the game runs counter to the media takeovers of test matches. Murdoch capitalism has become a paradigm. ‘Totalitarian regimes suppress reasoned dissent to their own cost, ultimately’ he sagely advises, but then, with the advent of Murdoch, he has to contemplate ‘A society which genuinely prefers fleeting fashions to matters of real substance, and simulated contests to actual competitiveness … ’.

Beatrice Faust, the token woman in this assembly, brings us right back into an area of genuine cultural and intellectual debate: the position of women. As she writes at the outset:

I am not an ideologue: I do not believe in feminism. Rather, I practise critique – the intellectual’s discipline. I study feminism, think about feminism, and publish my thoughts. I do feminist things. So this is an essay about constant interaction between theory and practice, hope and experience – not cataclysm but flux.

Appearing in this context, she invites herself to be read by men, and they will nod wisely at her critique of some of the more extreme feminist stances – and recognise also the cynical media manipulation (as in sport) that ‘prefers fleeting fashions to matters of real substance’.

One cannot help feeling, though, that she is writing from within the enemy camp, and I only hope her sense of goodwill towards the male section of society will not be used against her. She writes much good sense, but there are many lions out there, and they do not lick the hands of the thorn-takers.

Christopher Pearson sensibly regrets the polarisation techniques of gay activism, citing the Come Out ‘naming’ of people who have had same-sex encounters, though he doesn’t seem to mind doing a bit of ‘naming’ himself.

Frank Moorhouse, writing on the United Nations, seems, like Williamson, to be telling us more about his own novel Grand Days and its sequel, still-in-progress, and the resources he is digging into to research it. His proposal that Australia quit the UN might give us more of the flavour of his work to come, than present any argument against Australian political and economic commitment to this twentieth century dinosaur.

Les Murray does a Les Murray on the Literature Board. But then his real subject is The Bardic Mantle and its Divine Right. Les has had enormous and ongoing media space to develop his pet hates. It is a pity that he lacks the sort of scrupulous attention to fact, detail, and statistics that Frank Moorhouse uses to make his essay convincing.

Comments powered by CComment