- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Essay Collection

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

‘Curiosity is a muscle,’ Helen Garner declares in the first essay of this selection, displaying again the metaphorical spark that marks her out and keeps her readers plundering her pages. She is writing about writing, and her revelations couple a disarming intimacy – Garner the wry, lifelong apprentice, confiding trade secrets – with shrewd and reflexive moral admonition. Here, in a brief paragraph, is laid out the disciplinary ground of fiction and reportage, plus a private view of Garner’s workshop and tools: ‘Patience is a muscle,’ she continues. ‘What begins as a necessary exercise gradually becomes natural. And then immense landscapes open out in front of you.’ It’s a beguiling act, this ability of hers to be forever the journeywoman but in the assured allegorical diction of a latter-day Bunyan.

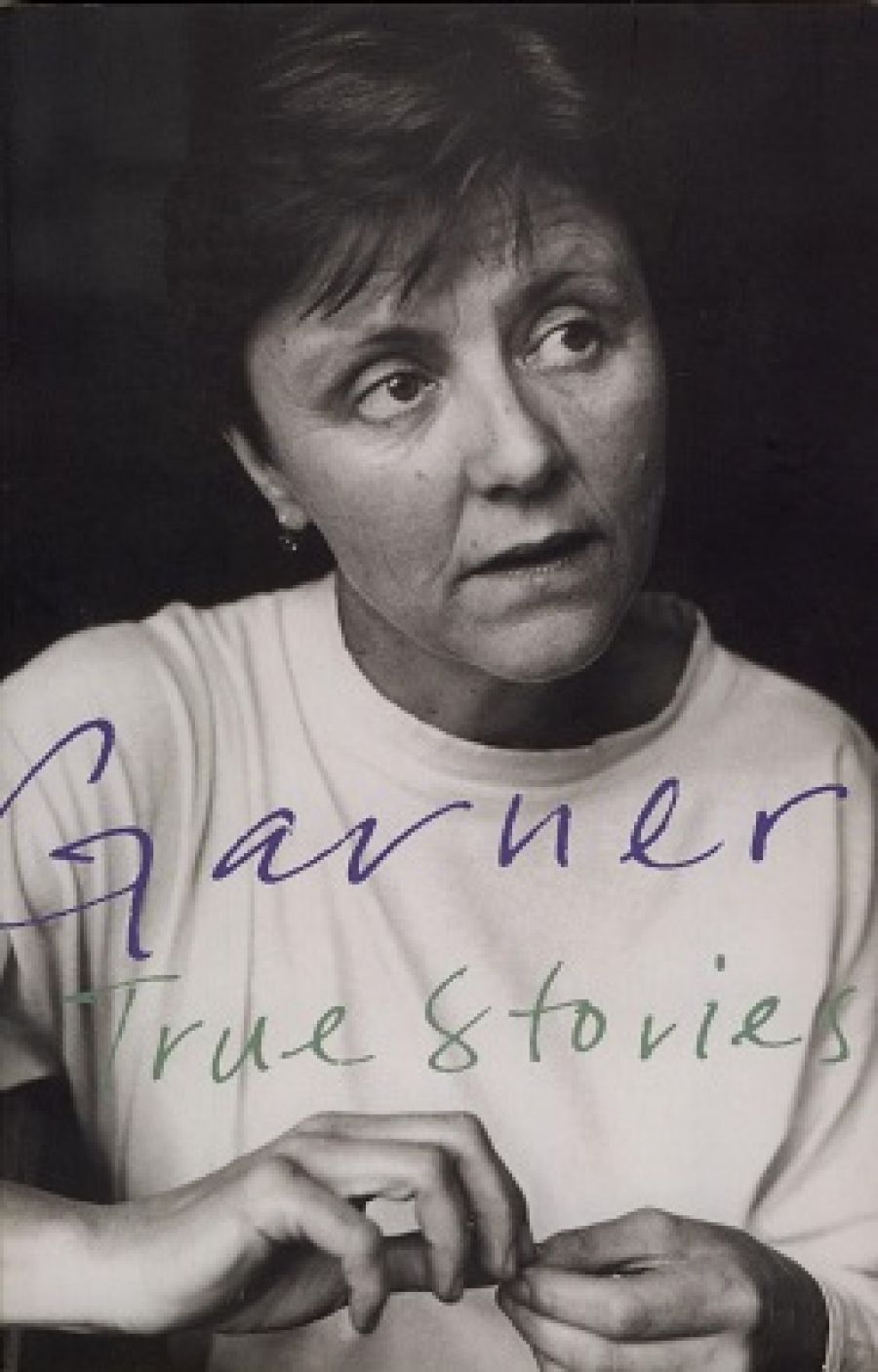

- Book 1 Title: True Stories

- Book 1 Biblio: Text Publishing, $19.95 pb, 242 pp,

- Book 1 Readings Link: booktopia.kh4ffx.net/2GOJ0

The ‘True’ of the title is provocative. You could read it as a side-swipe at last year’s criticism of her first extended non-fiction work, The First Stone (1995), but also as an astute marketing ploy: take it straight up to them. (Text, incidentally, is one of the few houses that regularly risks publishing volumes of troublesome essays, by the likes of Peter Singer and Robert Manne, that tug, invaluably, at the shape of our culture.) Garner’s 1995 critics, some of them journalists who were defending territorial as well as ethical imperatives, judged The First Stone to be shoddy journalism, or non-fiction, because its account of the Ormond College sexual harassment case was so refracted through Garner’s own sensibility and her formidable ‘subjective’ technique. Thus ‘true stories’ and its title can be read as a pre-emptive strike in an on-going argument about shifting boundaries between fiction and reportage, between ‘new’ and ‘old’ journalism. But there are also other and more subtle games being played here. Look at the tactic of the accompanying noun: these are true stories. That is, they are meticulously shaped, artful pieces of writing which filter an extraordinary precision of noticing through a moralist’s permeable skin. Garner, the assiduous stylist, is inevitably part of the story.

She does chalk out some seemingly clear ground rules. This, for example, in the overarching first essay, ‘The Art of the Dumb Question’:

As a non-fiction writer you have an implicit contract with your material and with the people you are writing about: you have to figure out an honourable balance between tact and honesty. You are accountable for the pain you can cause through misrepresentation: you have a responsibility to the ‘facts’ as you can discover them, and an obligation to make it clear when you have not been able to discover them.

But there are already complications here. Facts become ‘facts’. And writers, like Garner, who are obsessive and scrupulous crafters, will always be held responsible for the pain they cause by representation, not just by misrepresentation, by selection, by the exigencies of style. ‘One’s style is one’s inability to do otherwise’, she ruefully quotes Georges Braque as saying. Garner may not be comfortable with the dictum (she once wrote to Manning Clark, ‘grumbling that I was “sick of my style”. He wrote back a postcard saying bluntly, “your style will not change until you do”’) but she does wear the responsibilities that style generates, as attested by her post-First Stone stance. At the 1995 Melbourne Writers’ Festival she remarked that: ‘The question of writers who write about “real people” seems to me to be part of what is. I don’t see it as one of those problems that something ought to be done about.’ And again, in the same speech:

A writer who’s any good might save a bit of your life from oblivion. What a writer ‘takes’ from you might otherwise have been lost. In the long run, maybe that’s what writers are for. Writers aren’t necessarily nice people. Writers can be mean and lonely. But you need us. We exist. Live with it.

This is the punchy platform persona, the street fighter, and here she is talking specifically about fiction writing. But the comments cross over to her non-fiction without undue strain. Garner, in everything she writes, is as indelible stylist, a shaper of events, and a distiller of meaning. It is inconceivable that she would or could ever tum out bald, anonymous, reportage. If E. Annie Proulx can have her way with the shipping news imagine what Garner would do with the police rounds.

Not that style is something that she parades, or excuses as a kind of biological determinism, although she does register, with some alarm, the small degree to which a writer is actually in conscious control of the urges that drive her and give the bones to fiction or non-fiction narratives. In True Stories there are also other, complicating structural elements. There is, for example, both a confessional and analytical instinct at work, constantly defining and redefining a journalist’s – a writer’s – tasks and responsibilities. You could call this interrogative process a feminist technique, a way of splitting authority, multiplying perspectives, of allowing other possibilities to sneak into the frame. Garner can be candid and profoundly disconcerting; her observation is sometimes ruthless, occasionally devastating, but she is rarely magisterial.

In the essay, ‘At the Morgue’, for example, she allows herself, characteristically, to be tutored by the professional staff, and so the writing adapts its structure to the unfolding story. The technicians’ demeanour, she discovers, is not just a matter of professional detachment; it has more to do with a gravity of purpose and an unspoken regard for the meaning, the significance of the bodies that pass through their care. ‘So after a while I control myself and try to copy them. Some of their composure rubs off on me. It’s amazing how quickly you can get used to the company of the dead.’

The morgue technicians, Garner notes, do all their own cleaning because they understand that you can’t let just anyone, people whose motives might be mixed, into such a place. Equally, a journalist with less moral tact could have made a gruesome mess of Garner’s rare opportunity, but in her hands, the clinical details of death and dissection become a marvel of complex observation and integration. This is the kind of rich and precise humanity that critics looked for in vain in the prose of Helen Demidenko/Darville:

He places the body’s inner parts into a large plastic bag and inserts the hag into the emptied abdominal cavity; then he takes his needle again, threads it, and begins the process of sewing up the long slit in the body’s soft front. The stitch he uses is one I have never seen in ordinary sewing: it is unusually complex and very firm. He tugs at each stitch to make sure it is secure. The line of stitches he is creating is as neat and strong as a zip.

The body’s front, you register with glad shock, is ‘soft’. The post-mortem rituals are pieced together with the unusual seams of a still domestic routine. When a technician scours out an empty skull cavity Garner is reminded irresistibly of the wrist movements of her grandmother, scrubbing out a small saucepan.

True Stories spills over with such focused wonders. You come away from it alive to particular epiphanies, to the way the night sky changes weight when cloud has lifted (‘Three Acres, More or Less’), wise to the shifting façades of friendship and kinship, raw in the face of human vulnerability (‘Mr Tiarapu’), or the implacable needs of children. I read it alternately with Malcolm Bradbury’s Dangerous Pilgrimages, which is a grand, ironic, scholarly, sometimes satirical, Englishman’s sweep through transatlantic literature and culture in the twentieth century. Sometimes you want orchestral treatment. Certainly I do. But time and again – and this will happen over and over – I went back to True Stories as I do to the inimitable and abrasive Pablo Casals performance of Bach’s unaccompanied cello suites, for pitch-perfect tone, and for Garner’s uncanny, wild, and benevolent ear for the precise modulations of human experience.

Comments powered by CComment