- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Poetry

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

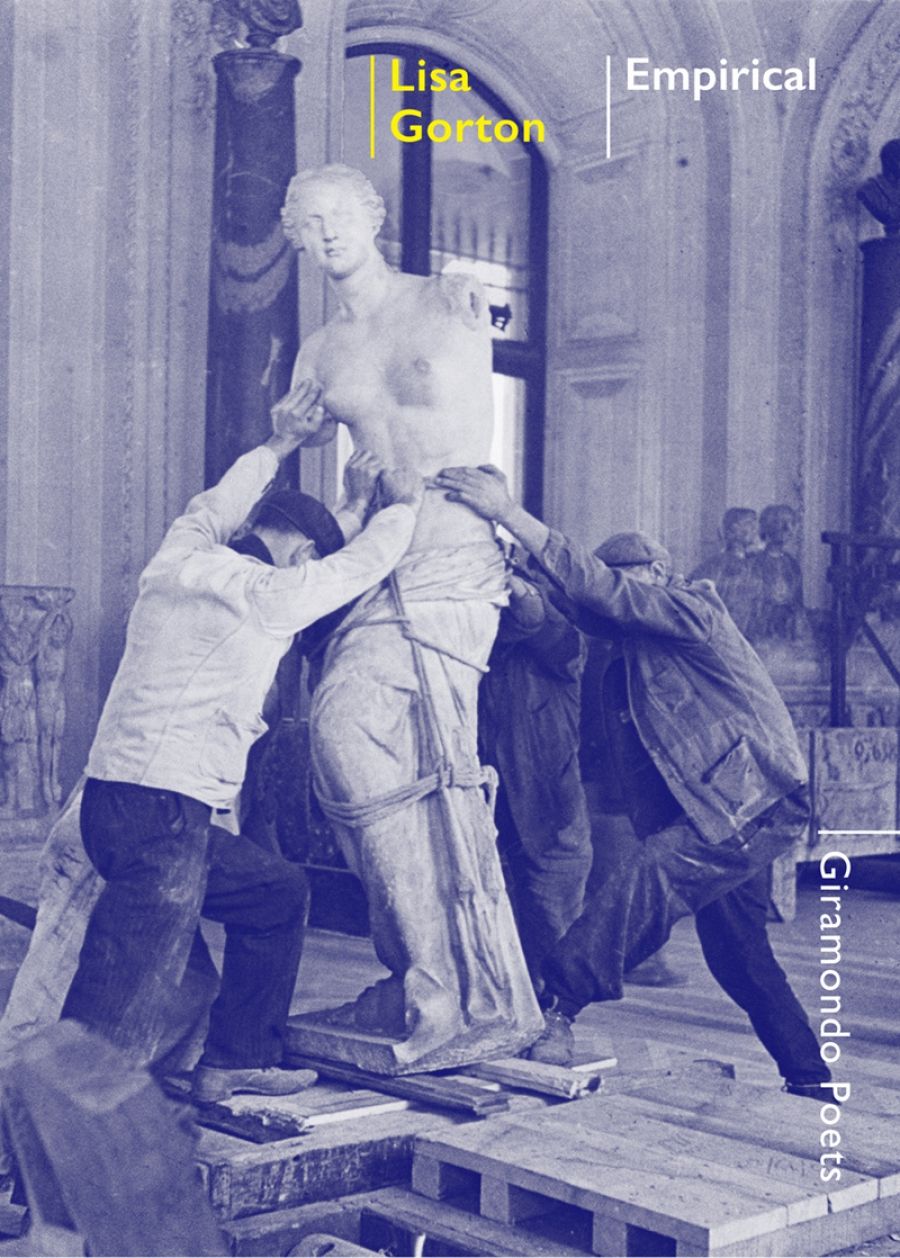

In her latest collection of poems, Empirical, Lisa Gorton demonstrates – definitively and elegantly – how large, apparently simple creative decisions (employing catalogues or lists; quoting from the archive; engaging in ekphrasis or description) can produce compelling and complex poetic forms.

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): Empirical

- Book 1 Title: Empirical

- Book 1 Biblio: Giramondo, $24 pb, 87 pp, 9781925818116

As the title Empirical suggests, Gorton is deeply concerned with things and the human observation of them. Thing-poems (Dinggedichte as the Germans call them) have featured in Gorton’s earlier work, but here the thing is the basic unit of poetic transformation. Empirical is concerned with a park (Royal Park in Melbourne, both materially and in the archive), a statue (Aphrodite of Melos), two poems by Rimbaud (about virtual cities), Crystal Palace (that Titanic architectural wonder of nineteenth-century cultural imperialism), a Romantic-era poem (‘Kubla Khan’), and magic lantern slides (which are in turn concerned with things).

Stylistically, in her rendering of these objects, Gorton is simultaneously classically austere and brilliantly baroque. It is hard to know whether she is offering plain renderings of the outré or elaborate versions of the quotidian. For instance, ‘Crystal Palace’ heaps detail upon detail in a way that is both highly stylised and documentary-like: ‘Mr Paxton sets the floorboards / a half-inch apart so the women’s skirts will sweep the floor clean – / Overhead clouds, like images in the mind of a reader, / replace themselves – a steam engine dragged in by sixteen horses – / a column of coal from Newcastle, sixteen-tonne weight – / the crane that raised the suspension bridge at Bangor – / the iron ore and the Sheffield blades – the elephant’s tusk / and Indian carvings in ivory – classic marbles of Paros …’ And so the list goes on, producing a sense of the paradoxical project of empire: to plunder the real to produce a virtual representation of itself.

Gorton is profoundly concerned with the specificity of objects in her empire of things; she is part anthologist, part bricoleur, and part historian. But it is notable that the things found in Empirical all occupy a suggestively liminal space between the real and the ideal, between representation and things-in-themselves. In addition, and despite their historical provenance, they all speak to contemporary concerns regarding empire, the environment, and the virtual condition of ‘reality’.

Lisa Gorton (photograph via Giramondo)

Lisa Gorton (photograph via Giramondo)

Unsurprisingly, poetry is one of the key discourses of virtuality under scrutiny in Empirical. As seen in the extraordinary ‘Life Writing’ (concerning Coleridge and his poem), the poetic method is seen to be a disguised version of the empirical method. Observation and the accumulation of data lead to (poetic) speculation and insight. Where poetry, as ‘Life Writing’ shows, diverges from the empirical method is the degree to which it is prepared to confuse the objective and the subjective realms, or rather show up the foundational confusion between those terms to begin with. This is nicely seen in Gorton’s rendering of Coleridge’s reminiscences of a younger contemporary:

In 1819 he walked with John Keats arm in arm along Millbank Lane – He didn’t believe in ghosts, he said, having seen too many of them – A prodigious walker in the mountains, he crept talkatively along flat city streets – ‘In those two Miles he broached a thousand things’ – Nightingales, poetry – Poetical sensation – Different genera and species of Dreams – Nightmairs – He couldn’t finish Christabel, he said, because it was the most impossible thing in Romantic poetry, witchery by daylight …

This Romantic expression of the dyadic relationship between the real and the virtual is a telling moment in Empirical, given how often the collection transcends apparently disjunct categories: subject and object; complexity and simplicity; real and virtual; human and non-human; original and repetition; poetry and prose. We see this capacity to undo opposing categories, too, in the way the collection is both regional (seen especially in the first section on Melbourne’s Royal Park) and transnational; deeply historical in orientation and intensely of the contemporary moment. Empirical is perhaps most especially notable in the way it fuses a (postmodern) transcriptive poetics with the (post-Romantic) intensity of lyric poetry.

Consistent with this condition is the way in which Empirical illustrates the continuity between the sensual and the cerebral. As the extensive list (another catalogue) of the concluding ‘Notes and Sources’ shows, Gorton undertook an extraordinary amount of labour to produce this beautiful body of work. In this non-violent use of ‘textual resources’, Empirical shows poetry to be perhaps at its most radical in its capacity to engender compelling transformations without engaging in dissection, plunder, or dispossession. In that way, and in others, Empirical is an astonishing achievement.

Comments powered by CComment