- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Memoir

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

This autobiography by Tim Costello – Baptist minister, lawyer, anti-casino activist, CEO of World Vision Australia for thirteen years – is a clear and straightforward account of his life, free of obvious literary artifice. What Costello has tried to do, he says, is to understand and explain how his memories and experiences ...

- Featured Image (400px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Featured Image): Tim Costello

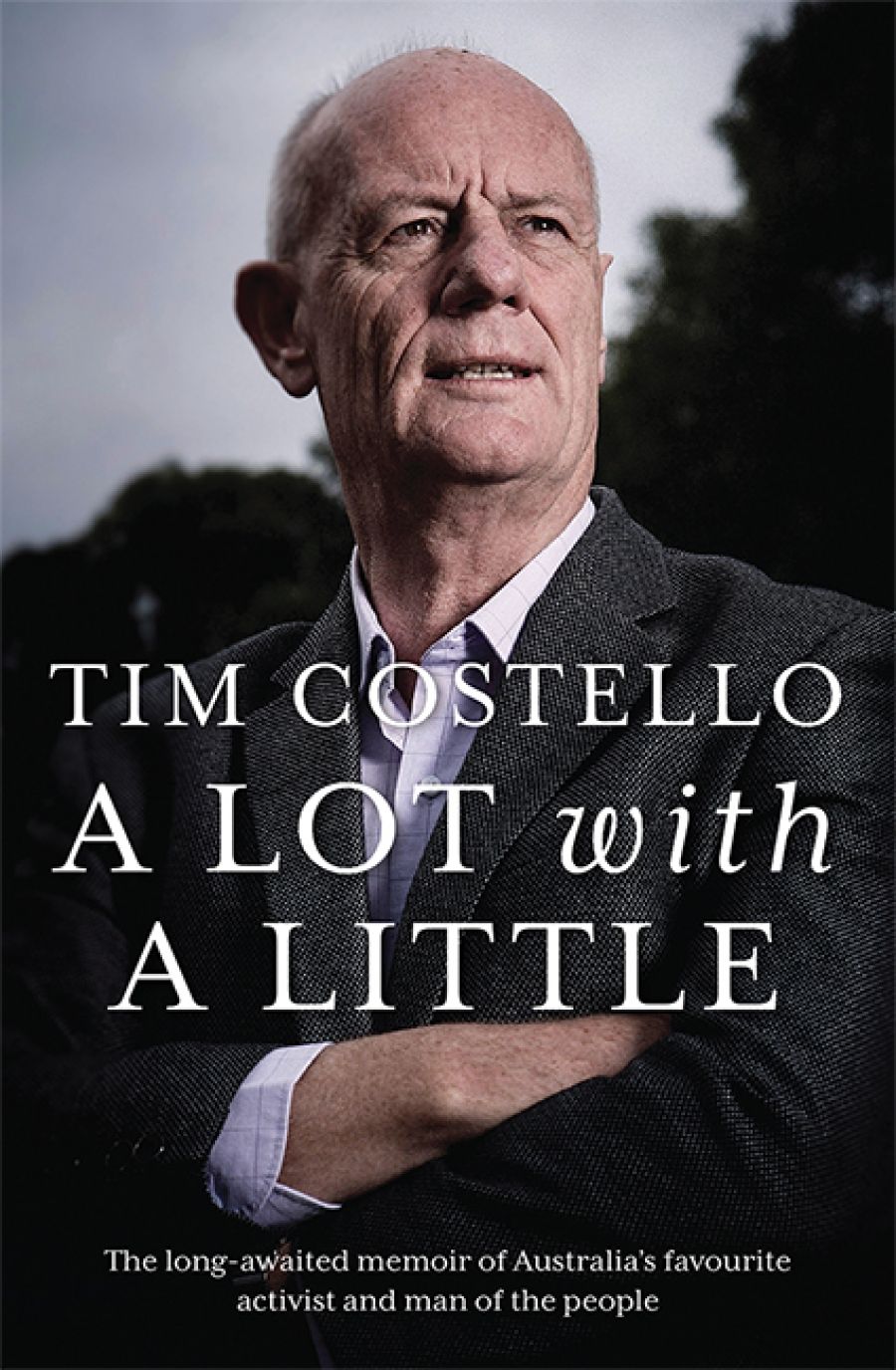

- Book 1 Title: Tim Costello

- Book 1 Subtitle: A lot with a little

- Book 1 Biblio: Hardie Grant Books, $45 hb, 336 pp, 9781743795521

They were all staunch members of the Baptist church. (Anne noted that her children all became ministers: the Honourable Peter and the Revs Tim and Janet.) However, their family life was less harmonious than this statement implies. Russell was austere, reserved, and a strict disciplinarian, not much of a reader except for the Bible. Anne, on the other hand, was sociable, loved books, and was vitally interested in the world around her. Though Costello does not say so, his mother evidently craved a bigger life, like so many women of her time. And like so many thwarted women, she encouraged her children, especially her two sons, to be competitive and to make their mark on the world. Costello writes: ‘My mother’s message to us was that we were the best, we must succeed, and we must impress the right people. Dad wasn’t the slightest bit interested in success. For him it was character and faithfulness and staying true to the vision of God’s will.’ Costello says he absorbed both lessons: ‘My bookends in life had been Dad’s faith, which was unswerving and committed at the core, and Mum’s faith, which was open at the edges.’ And though he does not spell this out, it is not difficult to see that the parents’ marriage, and Costello family life generally, had its tensions and conflicts.

One of the most interesting aspects of this book is Costello’s tracing of these contrasting views of life and faith in his own life and that of his brother. (Janet, who became a teacher and Baptist church worker, doesn’t really get much of a mention.) Peter seems to have absorbed his mother’s message about getting ahead more comprehensively than his brother: he was always very disciplined and focused, determined to succeed in his own world of the law and politics – despite his father’s innate suspicion of both. When he entered politics, he was told to play down his religious background for fear of being considered some kind of fanatic.

Tim, on the other hand, has made it his business to explore the relationship between religious faith and ethical action, and Christianity’s engagement with moral problems. He notes sardonically that Peter’s entry into Parliament in 1986 made him the favoured son, leaving Tim to his ‘random and obscure career in a storefront poverty law practice and as a minister’. It’s very clear that both sons very much wanted their father’s approval, with varying success at different times.

So how well do Tim and Peter get on? Reasonably well most of the time seems to be the answer, though, like most siblings, they have had their moments. The media have been setting the two brothers against each other, he says, for almost their whole public lives, most notably when, in 2003, Tim became CEO of World Vision, an organisation whose aid policy directly contradicted that of the government in which Peter was treasurer. However, Tim and Peter were part of the Indigenous Reconciliation march across Sydney Harbour Bridge in 2000. Tim deals gracefully with Peter’s failure to become Liberal Party leader and his decision to leave Parliament, saying only that Peter’s disillusionment obviously overcame his usual party loyalty.

Peter six years old and Tim eight years old in the lounge room at Blackburn in 1962.

Peter six years old and Tim eight years old in the lounge room at Blackburn in 1962.

Writing about deep religious faith is always tricky, especially in an autobiography. It is so easy to sound either hectoring or, worse, smug. Costello avoids both these traps, largely because he concentrates on his own religious evolution, the questions he asked himself about the basis of his faith, his conflicts with his father, and his use of his legal skills to try and achieve social justice. He’s telling his story, not making a series of bland assertions. Faith means taking risks, he says, and he gradually learned how to express his need to challenge power, not simply to accept it and the status quo.

He has some sharp comments about politics and evangelism, especially in the United States. In 2002 the Baptist World Conference refused to pass a motion congratulating President Jimmy Carter, a Baptist, on winning the Nobel Prize for Peace unless President George W. Bush was congratulated for invading Iraq in the same resolution. Religious people, Costello found, are not always good people, and the Church had become a prisoner of the Republican vision of a strong America. This view caused him to break totally with his pro-Reaganite father. Although he describes their argument lightly, saying that they quoted biblical texts to each other ‘like two gunslingers quick on the draw’, dissension was clearly painful.

In the last part of the book, Costello explains how World Vision works – managing not to sound as if he’s soliciting for funds – and manages to describe the good things he has done without sounding self-righteous, preening, or falsely modest. With rueful honesty, he describes the not-always-beneficial effect of his advocacy on his family life and his children.

Costello is writing as the public man, but he manages to combine the personal and the political in a forthright, engaging way. Without community and connection, he says, we are doomed. It’s difficult to disagree.

Comments powered by CComment