- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Biography

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): Don Dunstan

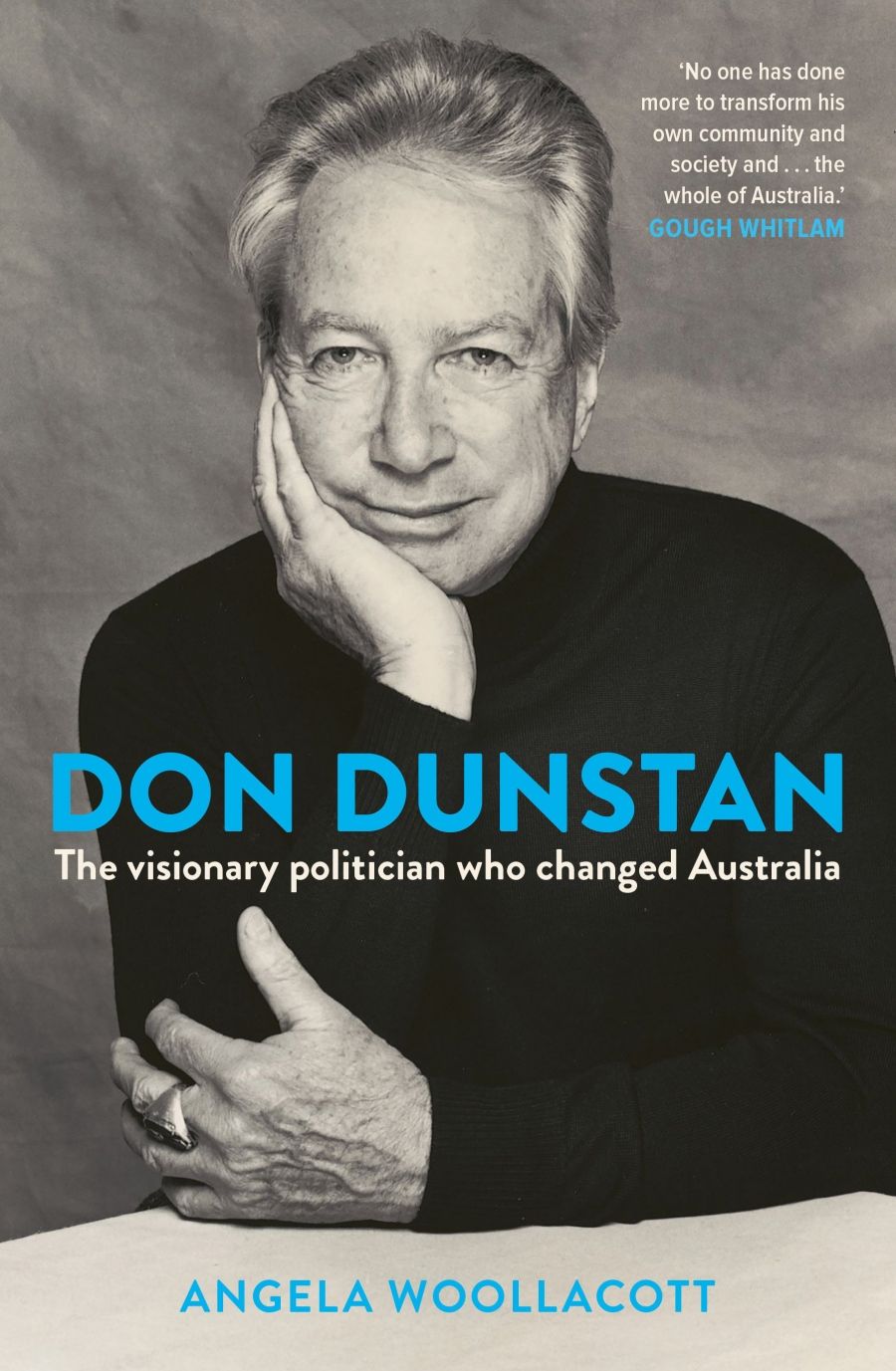

- Book 1 Title: Don Dunstan

- Book 1 Subtitle: The visionary politician who changed Australia

- Book 1 Biblio: Allen & Unwin, $32.99 pb, 344 pp, 9781760631819

The Establishment thought of him as a class traitor with, gossip had it, a touch of the tar brush. He supported Aboriginal rights and was responsible for removing the White Australia Policy from Labor policy. With his pebble glasses and stoop, he did not fit Labor stereotypes. He systematically transformed himself. He acquired contact lenses and developed his physique by regular attendance at a gym, long before this became fashionable. He found his voice. He could debate policy and legal details, sway crowds, and connect in the pub. His voice never lost its educated accent or resonance, but his passionate commitment was persuasive.

Dunstan became ‘the visionary politician who changed Australia’, as Angela Woollacott subtitles her biography. With admirable elegance and impeccable historical judgement, she traces the story of his election as the Labor MP for Norwood in suburban Adelaide, his role in federal Labor and his rise to become the stylish reforming premier of South Australia (1967–68 and 1970–79). She wears her scholarship lightly, weaving a gripping personal story with a nuanced account of the social changes of the period. Never ponderous or didactic, she keeps a tight control over the material. The reader is in safe hands. From his early contributions to national ALP policy, through the complexities of his last year in power, Woollacott lays out the story with clarity. The extended footnotes show just how widely she ranged, from policy documents, archives, school records, personal conversations, and journalism. To take just one example, notes in Chapter Thirteen cite a Mike Walsh television interview from 1980, a 2017 email from Mike Rann to Woollacott, and a letter from Shirley Hazzard to Dunstan in 1979.

Woollacott’s achievement is the more remarkable because Dunstan’s friends and acquaintances had such widely different views of him. Dunstan segmented his life. My own perspective was as a family friend, just one of mutually exclusive groups who claimed him as their own. It is difficult for a single narrative to encompass the statesman, the cultural figure, the exotic cook, and the gay icon. Woollacott is never prurient, but nor does she fight shy of the complexity. She connects Dunstan’s sense of justice and his youth in Fiji, traces his life as a passionate cook and sensualist from a tropical childhood, and identifies his vulnerabilities and need for loyalty. Woollacott describes Dunstan’s personal life with considerable tact. She deals dispassionately with the separation from Gretel, by then a lecturer at Adelaide University; the death of Adele Koh, his second wife; his unsavoury friend John Ceruto; and his last partner, Stephen Cheng.

Steven Cheng and Don Dunstan in their garden, 1989 (photograph courtesy of Steven Cheng)

Steven Cheng and Don Dunstan in their garden, 1989 (photograph courtesy of Steven Cheng)

Dunstan’s vision brought together Fabian views with a personal sense of fair play and respect for individuals. In addition to fighting for Aboriginal rights, he also developed close friendships with the community, as he did with migrant groups. He became a strong advocate for Australia’s links with Asia. He valued the environment and fought to protect Adelaide from developers. He promoted it not as the city of churches but as a vibrant festival city, with a European café culture and tolerant attitudes. He was an early supporter of second-wave feminism, equal pay for women, and abortion law reform. His defence of his views was always robust. He was intolerant of those who disagreed with him. He could be scathing, whether about the South Australian gerrymander, inappropriate police action, or others’ slowness to understand.

Woollacott is masterly in her management of material. Chapter headings give the flavour of her approach: ‘Member for Norwood’, ‘Labor Supreme at Last’, ‘Adelaide Is Not Canberra’. ‘The Perfect Storm’ describes Dunstan’s last year in office, when he dismissed the state police commissioner, Harold Salisbury, on the grounds that he refused to destroy police files when directed by the government. Woollacott describes Salisbury’s views: ‘In refusing to resign, Salisbury would explain, bizarrely, that he believed he was answerable “to the law … to the Crown and not to any politically elected government”.’ That ‘bizarrely’ is as judgemental as Woollacott gets. Dunstan’s ill health and resignation is searingly sad, in part because it is presented with such restraint. Hubris there may have been, but the story is a tragedy. The final chapters, ‘New Careers’ and ‘Final Acts’, have an elegiac tone, as if the final chapters of the Greek tragedies Dunstan himself loved so well.

A biography of Don Dunstan is well overdue. Woollacott has done an exemplary job of a task that has defeated many. Dunstan had a quick and sharp wit. He was verbally competitive even in social situations, and certainly in political life. He loved to laugh. Even if his inimitable voice can’t always be heard here, those well-rounded tones in elegant phrases, even if something is still missing, this is as informed a portrait as we’re likely to get.

Comments powered by CComment