- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Art

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Macmillan’s Albert Tucker is a pioneering venture. It is not just another well-arranged, well-printed collection of paintings by a notable painter, it is an endeavour to present the whole conspectus of a painter’s work and mind.

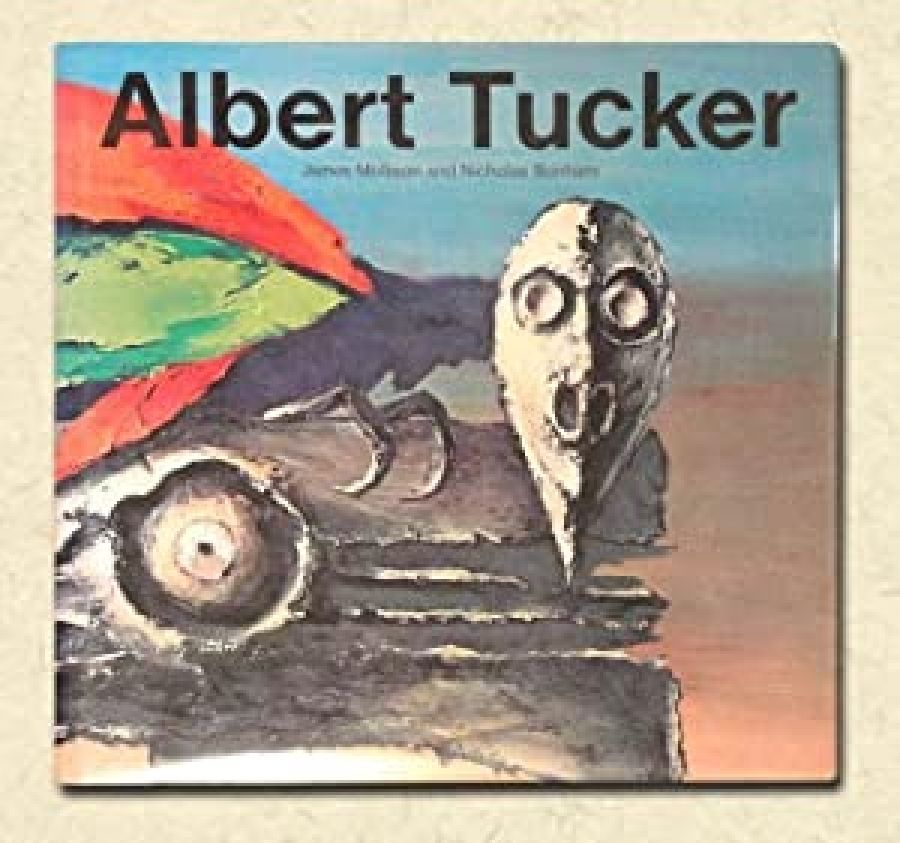

- Book 1 Title: Albert Tucker

- Book 1 Biblio: Macmillan, 144 pp, $35 hb

I have known Tucker for a good deal of his painting life, here and abroad. That, as a man of sensibility and imagination, he has been tormented, alienated even, by grossness and futility in the human condition, is plainly true. As a man, that is. But not as an artist. For, when you look at Tucker’s work in conspectus, I think you will see it as a sustained – not expression of – but triumphing over the grossness and futility, torment and tragedy, of the human condition.

Take Tucker’s paintings of the early and mid-1940s – the Images of Modern Evil period. Take three paintings of this period reproduced in the Mollison/Bonham book. First, that called The Futile City. A futile city perhaps. But not a futile painting. A painting, indeed, presided over by blood-red sunset, or could it be sunrise, clouds, and locked up, or perhaps locked open, with a marvellous mauve giant’s key. No, no city could be wholly futile that has given the world a painting such as this one.

Then, Psycho. A great dark-gaudy parrot’s wing of a human head. With one great black-and-white eye staring transfixed by some sort of death or destruction, while, outflanking it from behind an iron bar of a nose, a second eye, a sky-blue eye, peeks slyly but quite confidently out toward some manic or other kind of last hope.

And third, the 1945 painting called Night Image Eleven. The received image on this painting is that it sprang from Tucker nearly getting run down by a tram. But even out of this nightmare experience of the man Tucker, the artist Tucker, the Australian artist, rises in recognition of the right of a tram to be a tram. Tucker’s Night Image tram is a tram triumphant, a dark-bright, yellow-eyed, red-button-nosed archetypal monster of a tram barrelling on forever down the lines of an everlasting tramdom.

On page seventy of Macmillan’s Albert Tucker, Tucker tells Mollison and Bonham that:

I couldn’t survive if I didn’t have an immeasurable kind of faith in some benevolent, invisible, but vast omnipotent power, which helps make sense out of everything that is happening to us in this life.

Now, it’s important to know that Tucker’s omnipotent unseen power is no ordinary omnipotent unseen power. It is very much an Australian power, an Australian metaphysic.

How does this Australian metaphysic of Tucker’s show itself, work?

Well, it has always seemed to me that Tucker’s use of light – light and space is one of his most creative, effective and distinctive talents. English ballet critic Arnold Haskell told us back in the 1930s that Australian light was really quite as good as Mediterranean light. I have seen Mediterranean and many other lights. And none of them compares to Australian light.

Australian light, over the Simpson Desert, Bass Strait, the Great Dividing Range, is a splendour in itself. It is also the world’s most matter-of-fact light that strips objects of auras and shows bloody shovels for the plain spades they are. Above everything, Australian light is a last-frontier light ... an antipodean light ... a light at the other pole of the world from the light of Europe.

It is this light in which European man once had a God-sent opportunity to see himself freed from the trappings and constraints of the Old World social moment, to see himself standing anew on a grandly open antipodean stage of physical nature under a grandly open light from antipodean heaven. European man had that opportunity – and we have seen what he did and didn’t do with it.

It is this man, European man in his Australian aspect, whom Tucker has made central to his orchestration of his vision of the human condition. Early on in Australia, abroad in Europe and America, and back home in Australia, Tucker has used all his powers of observation, compassion and creation to place this man squarely in the light of our common day – and of God. This man, in Tucker’s painting, does get that celebrated Australian fair go, is not just allowed but is prodded and pulled into strutting and preening, conniving and killing, aspiring and despairing, for all he is worth.

Tucker’s painting is not just an act of representation. It is an act of faith – faith in the truth and in the power of art to save truth from quotidian futility. More specifically even – Tucker as an Australian knows that only the truth, the stark naked truth, can stand up here in the antipodes.

Tucker knows that in the chiaroscuro of Europe the time can be any time, but here in the antipodes it is high noon. And, at that, a high noon of confrontation. Between man and nature. Man and man. Man and himself. Man and God.

Tucker may tell Richard Haese or Mollison and Bonham of his alienation from society. But what Tucker is alienated from is not so much society as that downwards-towards-oblivion slope society has turned itself into, and the Gadarene rush of individual suicides we are all committing on our ways down that slope to the final mass suicide of all.

So much, I think, that is striking and undiminishing in power in Tucker’s painting can be seen as some sort of attempt to arrest an act of passing, of wearing away or destruction, of suicide.

To arrest the act and present it both for its revelation of a segment of the human condition and for its message to that omnipotent unseen upstairs power of Tucker’s a message that we here down on earth have gone just about as far as we can in our present resource-juncture.

Tucker paints the dilemmas of man, for themselves, and for how they add up to a dilemma of God. Tucker paints for the eye of George or William Mora, yes, but also for the eye-in-the-sky.

The Mollison/Bonham book will straightaway join Richard Haese’s Rebels and Precursors as a master contribution to the creation of a· canon of Australian modem art. Then, in its rightful and original self, the Mollison/Bonham book will be seen as taking the first long stride toward what we have been in need of – that public conspectus of Tucker’s physical and metaphysical dialectic.

Mollison and Bonham have assembled the first really balanced and substantial exposition in print of Tucker’s work. Starting with some already striking early portraits and self-portraits, in pencil, charcoal, coloured crayon, pen and ink, and oil, the Mollison/Bonham selection takes us through a starkly convincing cityscape or two, and on into the full range of Tucker’s Modern Evil period. Then comes Europe in the 1950s – and a preview of Tucker’s rambunctiously lyrical, though not his judgmental, work abroad.

Mollison and Tucker wind up with some of the very best of Tucker’s climactic home-on-the-range Australian paintings. It should also be noted that Mollison and Tucker accompany a number of the finished works with preparatory drawings for them – work of extraordinary interest in itself.

Let me hasten, however, to say that all this is only half of the Mollison/ Bonham book. The first half of the book is a masterly culling from taped interviews with Tucker by Mollison, Bonham, and James Gleeson. Mollison and Bonham have used skilled and sensitive questioning and editing to fuse the selection into something quite unique in my experience – a marvellously horizon-widening and spirit-invigorating illumination of an artist and his work. An artist whom Mollison and Bonham see coming into, as I do myself, a late and joyful period of painting.

In conclusion, may I briefly tum from painting to another of the arts, poetry.

Our newspaper headline writer saw Albert Tucker as the artist in torment. But wouldn’t it be truer and more useful to see him as Judith Wright saw some other fellow-Australians of ours:

So when the long drought-winds, sandpaper-harsh,

were still, and the air changed, and the clouds came,

and other birds were quiet in prayer or fear,

these knew their hour. Before the first far flash

lit up, or the first thunder spoke its name,

in heavy flight they came, till I could hear

the wild black cockatoos, tossed on the crest

of their high trees, crying the world’s unrest.

Tucker has cried the world’s unrest faithfully, variously and consummately, but always from the high crests of his great and triumphant art.

Comments powered by CComment