- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Architecture

- Review Article: Yes

- Custom Highlight Text:

Philip Johnson – lagging well behind the founding fathers – may not be the most profound architect of the twentieth century. Nor does he have the resonance of Louis Kahn or the form-changing genius of Frank Gehry, among his contemporaries. Yet the pattern of twentieth-century architecture cannot be fully understood without him ...

- Grid Image (300px * 250px):

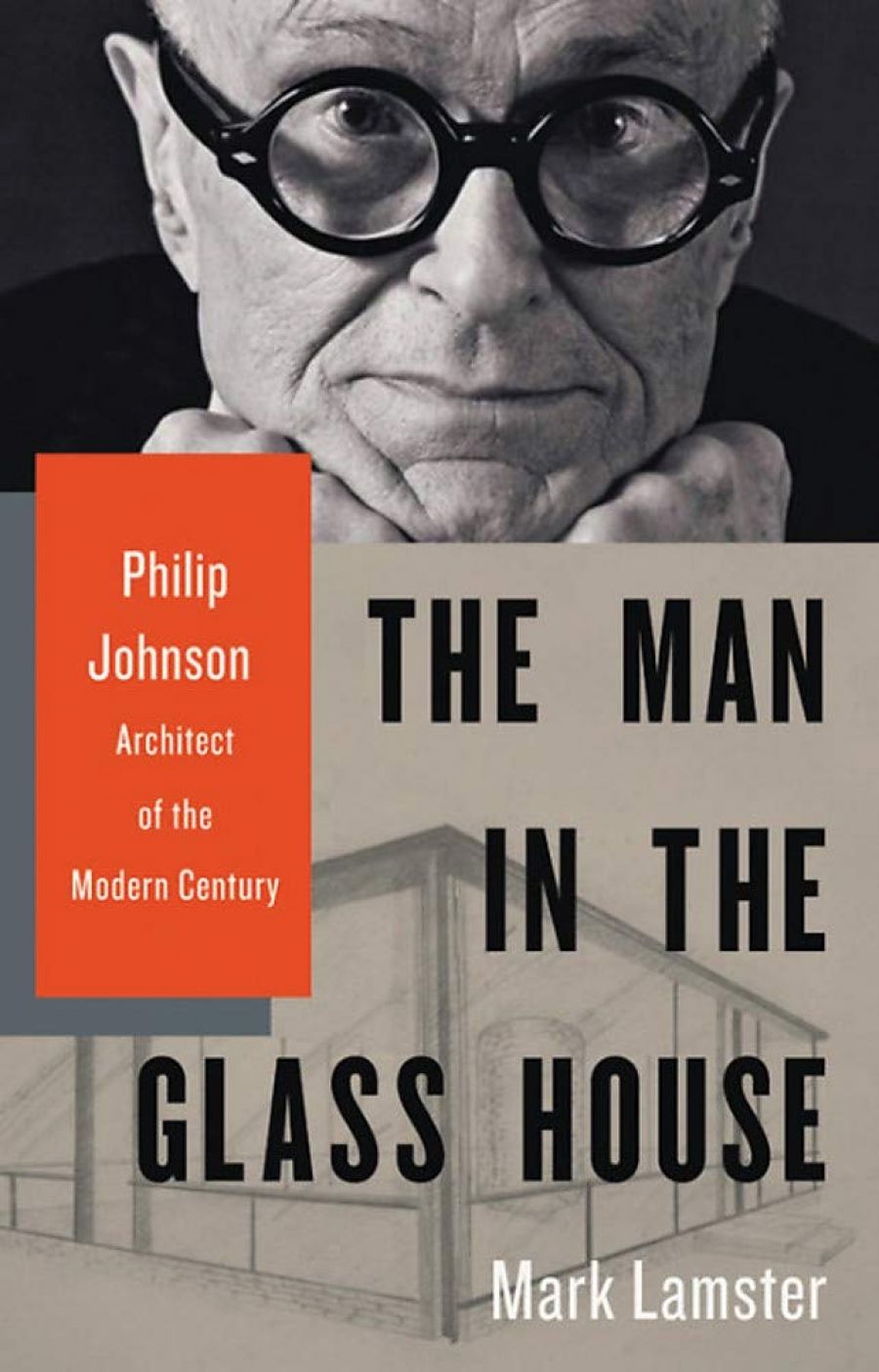

- Alt Tag (Grid Image): Patrick McCaughey reviews 'Man in the Glass House: Philip Johnson, architect of the modern century' by Mark Lamster

- Book 1 Title: Man in the Glass House

- Book 1 Subtitle: Philip Johnson, architect of the modern century

- Book 1 Biblio: Little, Brown, $49.99 hb, 510 pp, 99780316126434

With Hitchcock in tow, Johnson toured the sites of modern architecture in a luxurious Cord convertible collecting materials for an exhibition at MoMA: Modern Architecture: International Exhibition. Opening in February 1932, it became a landmark in the evolution of modern architecture and named the new European architecture of Mies van der Rohe, Walter Gropius, Le Corbusier, J.J.P. Oud, and their American followers as The International Style. Lamster is good on the genesis of the exhibition and the stress it placed on the young Johnson, then twenty-six years old. He ducked the opening and ‘checked himself into the Alice Fuller Leroy Sanitarium, a private hospital on the Upper East Side that catered to the well-heeled’. Dealing with Frank Lloyd Wright, nearly forty years Johnson’s senior, would put anyone into a sanitarium.

Two years later, Johnson followed it up with another enterprising exhibition, Machine Art. The show ranged from an aeroplane propeller to a vacuum cleaner to a dentist’s X-ray machine. Johnson’s installation was a masterpiece of minimalism. Nelson Rockefeller, a rising force at MoMA, lavishly praised Johnson: ‘I do not think that the Museum has ever put on a more beautifully arranged or interesting exhibition and the trustees … are extremely proud of the work you have done.’

Then ‘the boy king of New York’ lurched out of architecture, rightwards into fascism, from the home-grown variety of Huey Long and Father Charles Coughlin to the vortex of Nazism. Lincoln Kirstein published Johnson’s notorious essay ‘Architecture in the Third Reich’ in Hound & Horn in 1932. Naïvely, Johnson believed the new Germany of National Socialism would adopt the International Style as its own. He associated with American Nazi sympathisers, moving on to Ulrich von Gienanth, a German diplomat at the Washington Embassy in charge of Nazi propaganda, from whom he sought admission to a Nuremburg rally. He toured northern Poland with Viola Heise Bodenschatz, a German American whose brother-in-law was Göring’s Chief of Staff. In September 1940, Johnson ‘joined the foreign press corps on a supervised junket to the front under the aegis of the Propaganda Ministry’. He shared a room with William L. Shirer, the eminent journalist, who disliked him and suspected him of being a German spy. They witnessed the battleship Schleswig-Holstein shell and the Luftwaffe bomb the defenceless industrial port city of Gdynia. ‘We saw Warsaw and Modlin being bombed. It was a stirring spectacle,’ was Johnson’s considered response.

Johnson was a chameleon. During the war, he abandoned his right-wing politics and enrolled in the Harvard School of Architecture, determined to become a full practitioner. He found a plot of land on Ash Street just off fashionable Brattle and built himself a Miesian bungalow where he entertained his fellow students and the faculty with the aid of his maid and Portuguese butler. Johnson, a celebrity in architectural circles, had no difficulty in getting his Ash Street house accepted as his final-year thesis.

At the end of the war, Johnson elbowed his way back into the Department of Architecture at MoMA. In 1947, he curated a classic exhibition on Mies with the latter’s active participation. Lamster claims that as ‘a monographic architectural exhibition [it is] still unsurpassed in its influence’.

It stamped Johnson’s Miesian credentials, voiced superbly in his Glass House (1948–49) in New Canaan, Connecticut. Built entirely in glass and steel on a brick base, set on the edge of a cliff in a clearing of wood and field, no house marries so transparently the built and the natural. For the decade and a half following the Glass House, Johnson’s architecture had real distinction, from the early houses to his contribution to the Seagram Building, the sculpture garden at MoMA to the Dumbarton Oaks galleries. Johnson’s reputation soared, but his office remained light on jobs.

Philip Johnson's Glass House and pool in Connecticut (photograph via Carol M. Highsmith's America, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, via Wikimedia Commons)

Philip Johnson's Glass House and pool in Connecticut (photograph via Carol M. Highsmith's America, Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, via Wikimedia Commons)

In 1966 Johnson made his Faustian bargain for Towers and Powers, as Lamster calls it: he took on John Burgee as his partner. Burgee came from a large commercial practice in the Midwest. A businessman architect, efficient, hard charging, well versed in corporate speak, Burgee was personally ambitious. At thirty-three he demanded a full partnership. The office expanded; large-scale buildings began to flow in. Some notable work came out of the partnership, such as Pennzoil Place in Houston, the final salute to Mies with shaped twin towers in a taut curtain of glass and steel. The Lipstick Building redeemed Third Avenue in New York, and its controversial cousin, the AT&T building on Madison, with its Chippendale-inspired roof, added to the Manhattan skyline.

Burgee increasingly sidelined Johnson, and big buildings of little architectural merit went up across America in the firm’s name. Frustrated and impotent, Johnson played a meddling game from the touchline until Burgee drew up absurd conditions for Johnson’s limited participation in the office. The firm was renamed, clumsily, John Burgee Architects, Philip Johnson Consultant. Lamster’s account of the disintegration of the firm reads like a Bellowesque novella.

Johnson lived that down, and the ignominy of accepting work from a young New York developer called Donald Trump. In his last years, he became a revered architectural savant, sought out by a rising tide of major talents such as Frank Gehry and Peter Eisenman.

Johnson died in 2005 at ninety-nine, the emblem and idol of American architecture.

Comments powered by CComment