- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

Vietnam, of all the foreign conflicts in which Australians have been involved, most outgrew and out lived its military dimension. The ghosts of what Christopher J. Koch in this new novel calls ‘that long and bitter saga’ continue to haunt the lives (and the politics) of the generations of men and women who lived through it ...

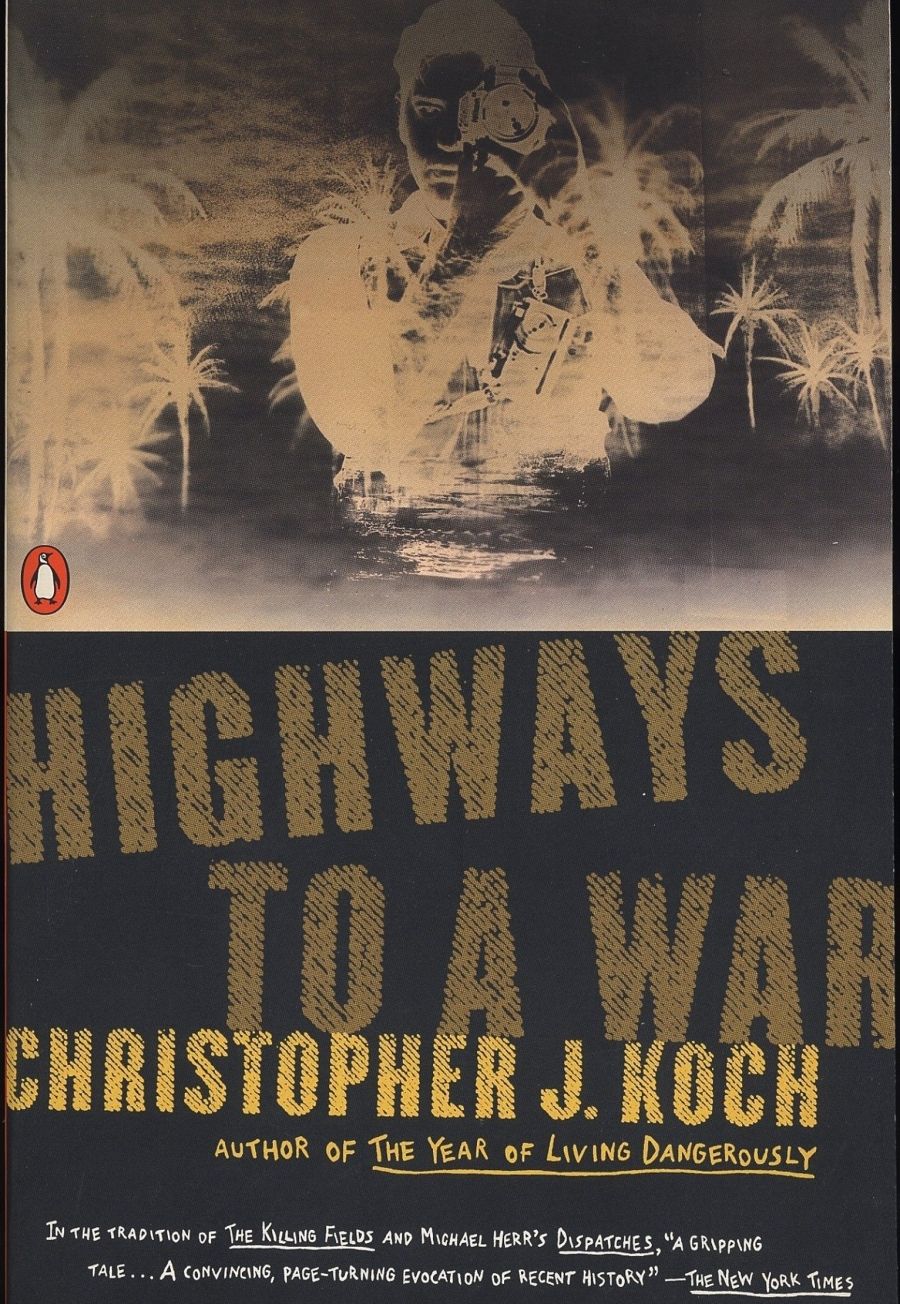

- Book 1 Title: Highways to a War

- Book 1 Biblio: WHA, $34.95 hb, 468 pp 0855616423

Much of the criticism was unfair. Koch’s synthesis of Eastern motifs with Western narrative forms in The Year of Living Dangerously remains one of the more sophisticated examples of what could be called the new Austral/Asian fiction. Earlier, in his second novel, Across the Sea Wall, Koch explored the imaginative possibilities of a rapprochement with Asia long before this became almost de rigueur. Yet Koch is also alert to the futility of exchanging one form of cultural allegiance for another. The ‘Asianisation’ of Australia, in Koch, is a matter of integrating a regional consciousness with the dominant Anglo-Saxon inheritance, not a simplistic rejection of one for the other.

I make these claims for Koch not merely to argue that he is an underrated, overlooked novelist, but to underline my disappointment with Highways to a War, his first novel in a decade. Koch has fashioned an entertaining and engrossing fiction out of the conflict in Indochina, and pays moving homage to the people who reported and filmed it. Yet, this time around, Koch struggles to make much of the familiar nexus of war, Asian travel and Australian identity that provides his thematic framework.

The dominating but enigmatic figure of Highways to a War is a Tasmanian photographer, Michael Langford. Aroused first by the sights, sounds and smells of Singapore circa 1965, Langford aborts a planned trip to Britain by lingering in Asia. He travels to ‘the best story going’, Vietnam, where he earns an international reputation as a risk-taking combat cameraman. From Vietnam he moves on to Cambodia (in which ‘all highways led to the war’), then rapidly moving towards its much-documented apocalypse. The deracinated Langford finds his home in Cambodia and dedicates himself to its freedom, a commitment which leads to his probably demise at the hands of the dreaded ‘Others’, the Khmer Rouge.

The novel begins with Langford’s disappearance in April 1976. A package containing some of his personal effects, including audio tapes and unpublished photographs, reaches a Launceston lawyer, a friend from his Tasmanian boyhood. ‘Font of history’, this unobtrusive narrator, an echo of the journalist Cookie who narrates The Year of Living Dangerously, pieces Langford’s story together from this documented material, plus the anecdotes of his comrades in the foreign press corps, one of whom is a Chinese cameraman (another reminder, for those familiar with the memorable figure of Bill Kwan, of the earlier novel).

Koch has acknowledged that one model for Langford is his fellow Tasmanian Neil Davis, who photographed combat in Indochina for several years before being killed covering a coup in Bangkok in 1985. But perhaps Langford more closely resembles Sean Flynn (son of Errol), the notoriously glamorous and gung-ho photographer, who disappeared in Cambodia in 1970. Intertextually, the novel suggest Margaret Drabble’s The Gates of Ivory, in which an Englishwoman tracks down the fate of a novelist friend who vanishes in Cambodia in the 1980s while ‘looking for copy’ for a planned play about Pol Pot.

The conflict in Indochina was a beanfeast for journalism, the place to be for an ambitious reporter. But whereas The Year of Living Dangerously offers a critique of the postures and practices of Western journalism in Third World ‘trouble spots’, Highways to a War is a fairly tame exploration of the psychological and sexual basis of warfare’s attraction to men (especially in Asia), much of which is honestly celebratory. This sort of thing has been done better before, by the American journalist Michael Herr in his memoir Dispatches, with its depiction of the collection of ‘thrill freaks’, ‘death-wishers’, and ‘hero-worshippers’ with whom he worked in Vietnam.

For all Langford’s commitment to Cambodia (embodied by his love affair with a beautiful Khmer patriot), Asia exists in this novel as a stage on which a thoroughly Anglo-Saxon drama is enacted. ‘Asia had swallowed him,’ the narrator tells us on the first page, in announcing Langford’s disappearance. It is odd that Koch, a long-time supporter of Australians ‘crossing the gap’ that culturally and geographically separates them from Asia, should thus resort to the old language of Australian insularity. Expressing a deep-seated fear of Asians that had been exacerbated by the actions of the Japanese during World War II, the Labor Opposition leader Arthur Calwell famously used the same image in 1964, in denouncing the military involvement in Vietnam on the grounds that he did not want to see more of his countrymen ‘swallowed by the quicksands of Asia’.

One of Koch’s great strengths is his ability to write ‘serious’ fiction in a popular mode. In Highways to a War, however, there is one wickedly attractive oriental femme fatale too many, and sometimes Koch resorts to travelogue, notably in his portrait of sensual Singapore circa 1965, before it was became ‘a sanitized metropolis of the late twentieth century’. The novel is suffused by a nostalgia for a picturesque colonial ‘East’ that has passed into history, as in the description of old Phnom Penh in the 1960s, ‘a French city on the Mekong coloured Mediterranean cream and ochre’, with its villas, restaurants and ‘intimate little nightclubs’.

An elegaic tone, indeed, dominates the entire novel – appropriate enough, one could say in Koch’s defence, for this excursion into the past, into a legendary war, and the doomed life of one venturesome Australian.

Comments powered by CComment