- Free Article: No

- Contents Category: Fiction

- Review Article: Yes

- Online Only: No

- Custom Highlight Text:

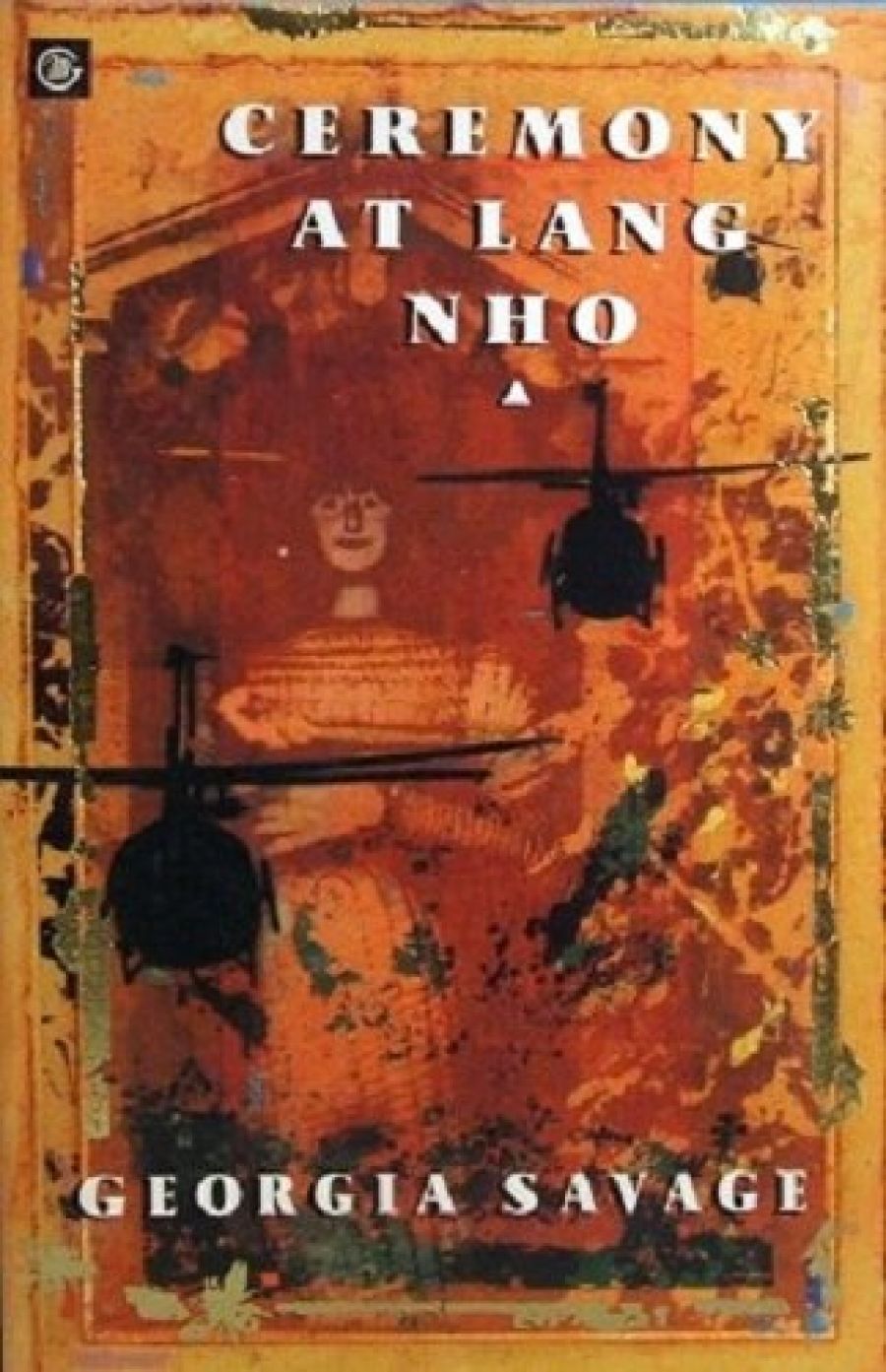

It would not be unreasonable, given the title and the cover (saffron-tinted, showing a vaguely Buddha-like image overlaid with helicopter gunships) to expect Ceremony at Lang Nho to be about Australia’s involvement in the Vietnam War. Well, we all know about judging books by their covers, don’t we? The image is no Buddha, but an elaborate twelfth-century European beehive, and the helicopter gunships are themselves overlaid by little golden bees. And the true battleground of this novel is not Vietnam but the family and the individual psyche.

- Book 1 Title: Ceremony at Lang Nho

- Book 1 Biblio: McPhee Gribble, $14.95

Fiona is the second of three sisters, daughters of a devastatingly beautiful and manipulative mother, Haldane. The oldest girl is the mother’s favourite, and very like her; the youngest survives by cultivating an in-your-face defiance. It’s this younger sister that Fiona identifies with and adores: ‘dearer to me than my arms, than my eyes even’. Georgia Savage does powerful sibling relationships so very well: brother/brother in Slate and Me and Blanche McBride, brother/sister in The House Tibet, and now sister/sister, a courageous little bantam pair whose loyalty is unshakeable, in Ceremony at Lang Nho.

Heaven knows they need each other. Catastrophic losses are suffered early in Fiona’s life, beginning with the sudden death of her gentle, beloved father when she is eight, and followed by her dismissal like an unwanted dog or servant from the family home less than a year later when her mother remarries and becomes pregnant again. She’s just sent to live with her very nice aunt Caro down the road, but the child has been emotionally banished, and knows it.

Fiona is hungry for love, a love that can’t be removed or withdrawn. At thirteen she believes she’s found it, with a classmate named Kevin Francis James, nicknamed (like her sister) Jesse. These two fall deeply, truly, and sexually in love, and when they are found out, as inevitably they are, they are separated instantly and forever. It is this grievously wounding event that Ceremony at Lang Nho hinges upon. Throughout the novel we go forward and back, backward and forward, piecing together Fiona’s story of love and loss through many other stories, many other characters.

Too many, perhaps; several times I became thoroughly disoriented, unsure what has happened to whom, and when. Some of the characters seem not to advance the story one whit, but are just babbling away in the background. My biggest problem is with Dai Stevens, a Welsh journalist who wants to write a piece about Fiona’s late husband, a photographer named David who was injured in Vietnam during the war and died eight years later. He also wants, it seems, to have an affair with Fiona, but his decidedly peculiar wife, Jo, is unlikely to let that happen.

Now, the fifty or so pages we spend with Dai and his entourage do serve to give us a lot of information about Fiona’s marriage, but I would rather have been shown that, not told about it. And it’s Jo who gives Fiona the image of the twelfth-century beehive statue, but that could have been acquired without having these two oddballs buzzing around in our heads.

I grizzle about the intrusion of these and other, to my mind, extraneous characters because the heart of the story, Fiona’s coming to terms with the loss of her first lover, is so interesting, so powerful, and yet so hard to get at. What Fiona has done is to turn the figure of the boy Jesse James into what a Jungian analyst would call a Ghostly Lover or a Lost Prince. He is her ideal, her soulmate, and she would rather commune with this unattainable image than truly commit herself to a relationship with a real man. As she melodramatically tells Haldane years later, ‘There wasn’t a minute when my heart, my flesh, didn’t weep for Jesse James’. And yet she says this while refusing her mother’s offer to find him, knowing that he is at that moment in the same city and that her mother’s formidable resources would surely reap success where her own earlier teenage attempts at contact had failed.

Why do people behave as they do? This is the most fascinating question a novel can pose. For the reflective reader of Ceremony at Lang Nho there will be an intriguing journey to the answer that fits best and is most rewarding for them.

Comments powered by CComment